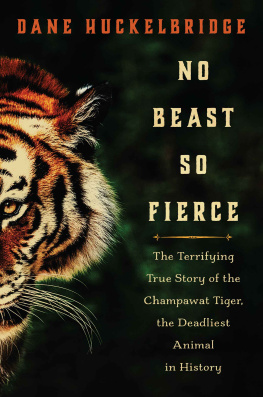

I TS A WARM March night in the East African Protectorate in 1898, the smooth, black air around the compound of Indian workmen soft with the promise of the coming rainy season. If there were more of a moon, the half-completed skeleton of the Tsavo Bridge would jut darkly some hundreds of yards away from the field of tents, which loom like strange, pointed khaki mushrooms clustered loosely about the dying eyes of scores of untended campfires. It has been a hard day of work for the more than 2,000 imported laborers, and now, at midnight, nearly all are asleep.

One tent, much like the rest, contains seven men: six laborers and one supervisor, Jemadar Ungan Singh, whose title denotes a rank of lieutenant in the Indian Army. He is nearest the open fly of the tent, snoring enough to awaken one of the coolies of his team. Irritated, the man sits up and rubs his eyes, glancing about the murk, over the sleeping forms of his fellows and out the door into the shadowy expanse of the open compound. Wiping away a film of sweat from the close night, he is about to lie back. One does not complain about the snoring of a superior, let alone a jemadar. But something catches his eye, something darker than the pale shadows, creeping slowly toward the open tent. He blinks as fear hooks his stomach with long claws, his eyes growing wider. In rising terror he stares as the form ghosts nearer, a tawny wraith flattened against the ground. It pauses for a heartbeat at the door, then instantly lunges at the sleeping Ungan Singh. Thick white fangs audibly clash against each other as they meet through the flesh of the Jemadars neck, yet he manages to give a strangled shout of Choro! Let go!before, with an irresistible lurch, he is pulled from the tent. At the last instant he is seen to wrap hisarm around the giant lions neck as he disappears into the night.

Ungan Singh does not die easily. Helpless in the lions jaws, he is dragged struggling through the thorns, futilely flailing the man-eater with his fists. Its likely that the jemadars unusual personal size and strength give the Sikh quite a few extra moments of unwelcome life as the cat continues to pull and carry him away from the growing clamor of shouts from the camp. The men back in the tent can clearly hear his repeated gargled attempts to scream, and the sounds of his struggle are terrible. After a hundred yards, fate shows some dark mercy in the shape of another huge lion, which charges forward and bites him deeply in the chest, killing the Indian. Irritated by the poor table manners of his partner, the first lion growls loudly, struggling to keep hold of his prey, tugging with all the steel-muscled power of his 500-pound body. As the long fangs tear and the pressure is increased, the mans head is torn completely off, rolling away to land, by chance, balanced on the stump of neck, the eyes still open wide and staring, dead pools of dread. Ignoring the head, the big cat snarls and leaps to grasp the decapitated corpse, fighting briefly with the second lion before both settle down to feed hungrily until the body is consumed but for scattered red scraps of flesh and a few bones. The Tsavo Man-eaters have just killed their third official victim, although quite probably Ungan Singh is actually number ten or eleven. This, however, is just a warm-up, a canape before the main course. Over the next nine months these two incredibly deadly animals will actually stall the largest colonial power in the world, that of Victorian Britain, bringing one of its most important construction projects to a complete halt and one of its less likely citizens to the status of an international hero.

It was known at home, back in Blighty, as the Lunatic Line, so dubbed by the London press and generally considered the screwiest exploit of an age not shy of sensationalism. Technically and officially called the Mombasa-Victoria-Uganda Railway, it was planned to run fromdamn near nowhere, the sweltering east coast port of Mombasa, to virtually the middle of nowhere, which in those days was a pretty fair description of Lake Victoria. On the face of it, especially in the light of todays technology, such an undertaking might not seem very unusual. But in the 1890s, things were a mite different. Most work was done by great gangs of hand labor over some of the toughest terrain south of Abyssinia. If the cost in pounds sterling was virtually obscene, it was downright cheap compared to the price in lives paid by the hordes of Indian coolies whose imported skills and experience were required as the only labor pool before the local Wajamousi, WaKikuyu and Masai started going to Yale and Oxford. Of the more than 35,000 Indians imported, nearly 9,000 were killed, died or were permanently maimed. More than 25,000 additional laborers of the same force were injured or taken ill, but recovered. The dark, coy virgin called Africa had a very hard bosom.

In itself, the Lunatic Line was a master stroke of nineteenth-century engineering and execution. Started at the coast in 1896, it was not completed until December 19, 1901. Ostensibly, it was created to help combat the slave trade, although the commercial advantages of a wilderness railroad running deep into the heart of Africas lake country are also obvious. In all, it twisted snakelike for 580 miles through the most indescribable nyika, or wilderness, northeast from Mombasa, across plains and over highlands, spanning rivers and gorges, passing through exotic stops such as Voi, Nairobi and the lakes of Naivasha, ending at last at Kisumu on Lake Victoria. To carve and burrow the Lunatic Line through the swamps and highlands by hand labor was an awful undertaking, but, despite the price, it struggled inexorably farther inland every day, foot by foot, rail by rail, mile by murderous mile until, in March of 1898, it touched the Tsavo River, 132 miles up the line. But of the 162 bridges that would have to be built, none would ever bear a name so synonymous with terror and abject human misery as Tsavo.