Contents

Page List

Guide

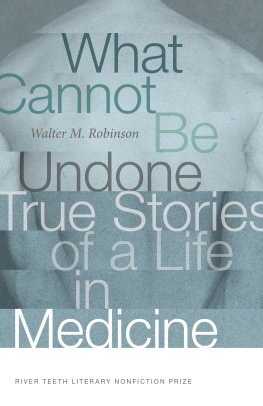

PRAISE FOR What Cannot Be Undone:

True Stories of a Life in Medicine

By showing us what is often hidden behind a white curtain, Dr. Walter Robinson explains how to reconcile ourselves, as others have, to sickness and to health. Everyone who has ever sweated it out in a hospital waiting room should read this astonishing book.Susan Cheever, author of Home Before Dark

What are the limits of the power of doctors, and of human beings? When should we intervene, and when it is our job to watch and to accept? Reading Walter Robinson is like getting stories from a brilliant war correspondent. Hes our man on the ground, and the ground is medicine, life, and death. A gorgeous and important book.Joan Wickersham, author of The Suicide Index: Putting My Fathers Death in Order and The News from Spain: Seven Variations on a Love Story

Among physician authors, Dr. Robinson stands out for his ability to peel away the common clichs and tropes that populate so much of this literary genre, giving us unflinching insights into both the utterly mundane as well as the truly extraordinary experiences of physicians and patients alike.Robert D. Truog, MD, director of the Center for Bioethics at Harvard Medical School and coauthor of Talking with Patients and Families about Medical Error: A Guide for Education and Practice

What Cannot Be Undone

RIVER TEETH LITERARY NONFICTION PRIZE

Daniel Lehman and Joe Mackall, Series Editors

The River Teeth Literary Nonfiction Prize is awarded

to the best work of literary nonfiction submitted

to the annual contest sponsored by River Teeth:

A Journal of Nonfiction Narrative.

Also available in the River Teeth Literary

Nonfiction Prize series:

The Rock Cycle by Kevin Honold

Try to Get Lost by Joan Frank

I Am a Stranger Here Myself by Debra Gwartney

MINE: Essays by Sarah Viren

Rough Crossing: An Alaskan Fisherwomans Memoir by Rosemary McGuire

The Girls in My Town: Essays by Angela Morales

What Cannot Be Undone

True Stories of a Life in Medicine

Walter M. Robinson

University of New Mexico Press / Albuquerque

2022 by Walter M. Robinson

All rights reserved. Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8263-6371-8 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-8263-6372-5 (electronic)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021948229

Founded in 1889, the University of New Mexico sits on the traditional homelands of the Pueblo of Sandia. The original peoples of New MexicoPueblo, Navajo, and Apachesince time immemorial have deep connections to the land and have made significant contributions to the broader community statewide. We honor the land itself and those who remain stewards of this land throughout the generations and also acknowledge our committed relationship to Indigenous peoples. We gratefully recognize our history.

Cover illustration: Marco Rosario Venturini Autieri / istockphoto.com

Designed by Mindy Basinger Hill

For Tom

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Physicians have written about their patients since the advent of the profession, but the patients in these stories did not come to see me because they wanted to be in a story. They came to me for medical care, and that is what I provided to the best of my ability.

Because I want to respect their privacy, I have in these essays disguised patients names and details in a manner that would make a journalist squirm: Sometimes I have combined two patients into one, sometimes I have given patients different families, sometimes I have rearranged the events of their care. I have put words in their mouths when I remember only the gist and nuance of what they said. I have changed the names and locations of my colleagues.

I have relied on my memory of events, and my memory is not perfect for all the details. Over the years, in trying to understand what it has meant to me to practice medicine, how it changed me as a person, I have told and retold these stories to myself in such a way that they have become the truth for me. And that is what I am seeking in this bookthe truth about what it has meant to me personally to practice medicine over the course of many years. I stand by that effort, errors and all.

The truth about American health care would make a terrible television show. Illness and death on the screen are not like illness and death on the wards. People are often surprised when they become patients or when their family members have serious illnesses that things are not at all what they expected. It is easy to sacrifice hard truth for easy drama. I cannot compete with the tidy endings and the all-knowing fictionaland saintlyversions of physicians available on TV. As these stories show, I am no saint, no hero, no wizard. On my best days as a doctor, I was ordinary.

That the stories here depict more of the sorrow than the joy of a life with serious illness is attributable to the writer and his circumstances. There are plenty of happy stories about life with serious illness, many of them written by people who know it best. I urge the reader to seek those stories out. The patients and families in these stories had to contend with my imperfections as a doctor and a human while they taught me what it means to live gracefully in the face of hope and tragedy. For that, I thank them, one and all.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people helped make these essays possible, but three people deserve special thanks: Susan Cheever, Ben Anastas, and Joan Wickersham. Susan Cheever had the wisdom to tell an overeducated physician to start over and keep going. Ben Anastas encouraged a weary man to get started writing again. Joan Wickersham taught a hesitant writer how to put just enough of himself on the page to make a good story. For being wonderful teachers and friends, I cannot thank each of you enough.

I would also like to thank my colleagues and fellow writers Denton Loving, Keith Lesmeister, Cassie Pruyn, Corina Zappia, Megan Galbraith, and Cathy Salibian for reading earlier drafts of these essays in spite of my repeated decisions to write mostly about things people would rather not discuss.

I would like the thank the editors of the journals that published my work, especially Christina Thompson at Harvard Review, who encouraged me more than she may know by calling one of my essays harrowing (but in a good way).

I would like to thank the Bennington Writing Seminars for changing my life for the better.

And thank you to Tom Bertrand, who makes everything worthwhile.

NOTE

Some of the essays in this book previously appeared, often in substantially different versions, in the following journals:

The Literary Review: Nurse Clappy Gets His

The Sun: This Will Sting and Burn (reprinted in Readers Digest)

Harvard Review: White Cloth Ribbons

AGNI: What Cannot Be Undone

Ruminate: White Coat, Black Habit

What Cannot Be Undone

WHAT CANNOT BE UNDONE

A thick row of white tape secures the boys arms to the steel armature above his head. Two nurses paint his scrawny chest with brown disinfectant, starting at the center where the incision will begin and arcing outward in practiced motions. The muscle relaxant flowing at half a milligram per minute into his largest vein has uncoupled his nerves from his muscles, but in spite of the drugs name he is not relaxed, not sprawled out in confident slumber on a bed as other fifteen-year-old boys might be. Children under anesthesia are not asleep so much as absent, or so I had come to think because the idea of masked strangers cutting open a sleeping body is a nightmare not just for the sleeper. So my mind removes this child from the scene, teleports him outside the normal, forward flow of time. Over decades of being a doctor, I have come to embrace useful illusions. Today, the illusion of this boys absence during the surgery permits me to acquiesce to the surgeon cutting his chest open.