Authors Note

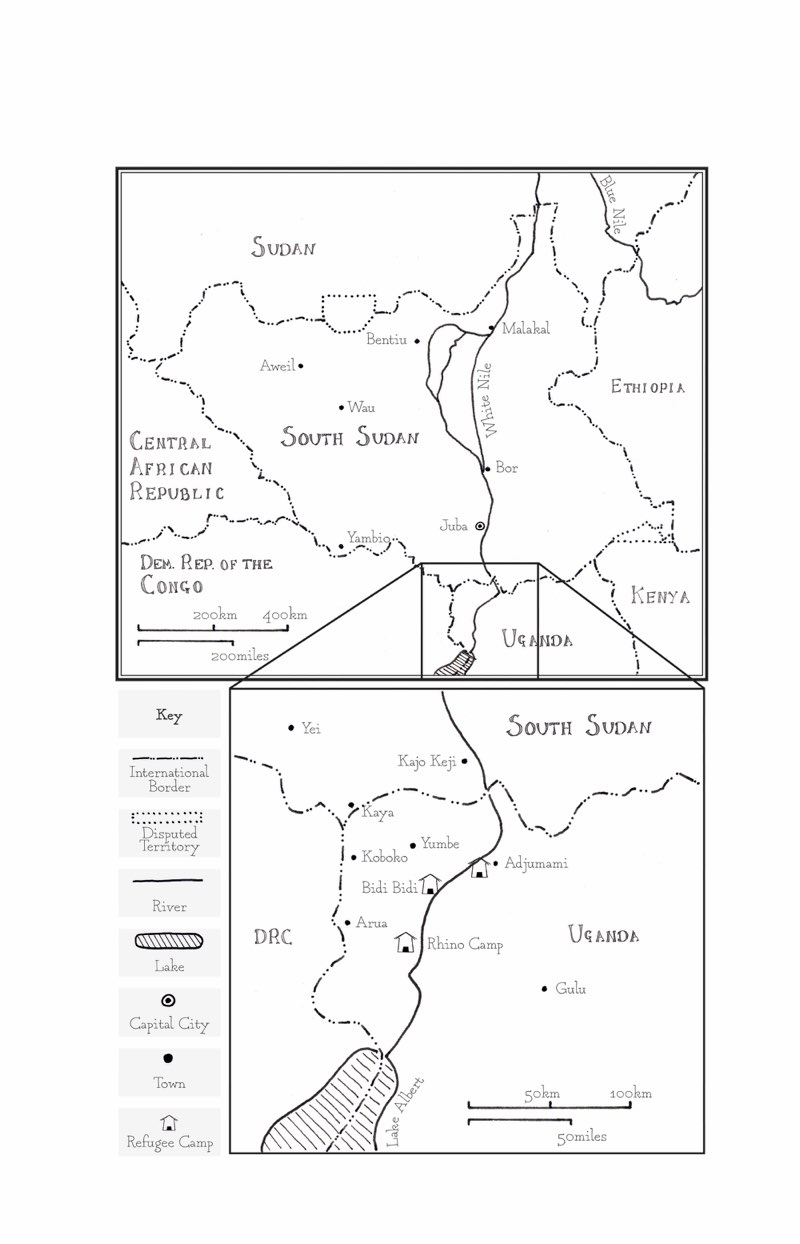

In 2016 civilians raced out of South Sudan, fleeing convulsions of violence in a three-year-old civil war. I was working as an editor for the Thomson Reuters Foundation on human rights stories, filing reports of the sudden and dramatic exodus. Hundreds of thousands of people were streaming across the border into Uganda on a scale not seen since the Rwandan genocide of 1994. Over the following months, Bidi Bidi refugee camp in Uganda, a city of sticks and tarpaulin, grew to become the largest in the world, home to a quarter of a million people. This was a region I knew from my years as a correspondent for Reuters in East Africa when I reported from South Sudan on its struggle for independence. I wanted to return to document the stories behind these astonishing numbers. This was a generation who should have been the first to grow up in a peaceful, independent South Sudan, but quickly they saw the lives they hoped for violently disappear.

I first arrived in Bidi Bidi in February 2018 on the back of a motorbike driven by a Ugandan mental health worker, James. He worked for a small charity that struggled to pay for the fuel needed to run their battered four-by-four vehicle around the five zones of the sprawling camp. Bidi Bidi, in the north-western corner of Uganda, covered a hundred square miles and took two hours to traverse along graded, murram roads and rutted tracks. Its low hills were dotted with tarp-roofed shelters, newly built mudbrick homes, acacia and neem trees.

Only registered refugees were allowed to stay overnight in the camp or settlement, as it was known as it had no fences or boundaries. The camp commander signed and stamped my clearance letter to visit in daytime. I stayed in a guest house in the small trading town of Yumbe, which was booming with the arrival of hundreds of mostly Ugandan aid workers recruited to help in the crisis. I visited the settlement each day but the lack of transport was a major constraint. The aid agencies War Child, Save the Children, the International Rescue Committee, World Vision and TPO helped me to access Bidi Bidi and later Rhino Camp and Nyumanzi settlement. The Franciscan Brothers kindly hosted me at Adraa Agricultural College in Nebbi where South Sudanese refugees had been enrolled on short courses.

All the people in this book and the events they describe are real. The main three characters Veronica, Daniel and Lilian asked me to use their own names, but I have changed the names of some family members and others who were unable to give their consent. The stories are drawn from extended in-person interviews conducted in February, March, October and November 2018 in northern Uganda and South Sudan and after that, many conversations by phone, WhatsApp and email. Daniel and Lilian spoke to me in fluent English. In interviews with Veronica I at first relied on Save the Children staff, or her neighbour Wilbur to translate from her native Arabic. But when I met her alone I discovered her English was quite competent and we were able to engage in conversation without an awkward male presence.

With introductions from aid workers and officials who supported me in the camp, I interviewed more than fifty refugees over several months and heard many stories, often heroic and heart-breaking, which have been hard to omit from this book. The characters who form the heart of the narrative stood out, as not only did they have remarkable stories to tell, but they were keen to tell them. They were willing to accept me into their homes, allowed me to follow their daily routines and patiently answered my questions. This means they are perhaps not a representative sample, but I am confident that their lives, while extraordinary, were unexceptional in the context of the camp. Similar tales of loss, courage, compassion and ambition were repeated over and over. Important, harrowing detail was often relayed in a brutally matter-of-fact manner or quickly skipped over as it was considered so mundane. The lives I have explored in the pages that follow are snapshots of a far wider refugee experience.

These are not my stories. Despite some authorial interventions to provide political background and context, I have chosen to remain absent from the narrative and I have tried to write closely from the protagonists perspectives. I have attempted as far as possible to replicate the inner thoughts of my characters as they described them to me. I do not know what goes on inside their heads but I have tried to construct a realistic narrative from their descriptions of their journeys, conversations, emotions and life events. The intimacy of some of the accounts reflects the startling openness and generosity of Veronica, Daniel, Lilian, Asha and others during our conversations. All of the dialogue in the book comes from their own descriptions and accounts, however, I have sometimes used literary licence to reconstruct experiences or interactions and I have also had to alter the chronology of some personal events in order to give the narrative shape and momentum.

I documented the experiences of the protagonists with written notes, audio recordings and photos and video. In the course of my reporting I also spoke to aid workers, community volunteers, teachers, health workers, religious leaders, government officials and UNHCR representatives. I was helped with fact-checking by Christine Wani, a journalist and South Sudanese refugee living in Bidi Bidi. I visited the South Sudanese capital Juba in October 2018 to research the events described in the book and better understand the environment from which the refugees fled, where I was assisted by the Reuters correspondent Denis Dumo. I have also relied on news articles, human rights reports, publications by academics and researchers and books about South Sudans civil war.

The title The End of Where We Begin is derived from a Dinka blessing to the Earth. In the context of this book, however, it illustrates the injustice of young lives brutally interrupted by war. While the rightful expectations of these three young people have been snatched away, I hope that in illuminating their search for meaning and opportunity amid extremes of violence and exile I challenge the often stereotyped narrative of refugees. The following pages explore the consequences of civil war in a fragile African nation, but although specific to a time and place, I hope the stories of Veronica, Daniel and Lilian resonate beyond the confines of the refugee camp where I met them.