2013 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cairns, Kathleen A., 1946

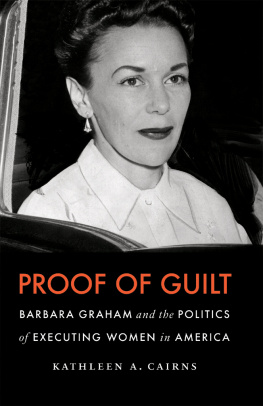

Proof of guilt : Barbara Graham and the politics of executing women in America / Kathleen A. Cairns. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8032-3009-5 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Graham, Barbara, 19231955.

2. Women murderersCaliforniaCase studies. 3. Women death row inmatesUnited StatesCase studies. 4. Capital punishmentUnited States. I. Title.

HV 8701. G 73 C 35 2013

364.66092dc23 2012039747

Set in Sabon Next by Laura Wellington.

Designed by Nathan Putens.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Illustrations

Following page 106

Authors Note

VERY FEW PEOPLE profess neutrality when it comes to the death penalty, and I am no exception. During my working life Ive been on both sides of the issue. As a young newspaper reporter in the post-Watergate era, I was a staunch opponent of capital punishment, believing it to be a barbaric relic of a medieval past. Then I was assigned to the 1982 Los Angeles trial of Freeway Killer William Bonin. A thoroughly repulsive individual, he kidnapped and murdered at least a dozen teenage boys and young men, whose bodies he dumped along Southern California freeways. Every morning the victims mothers sat huddled together inside the courtroom. Bonin looked like such an ordinary manpale, pudgy, and nondescriptyet he had done horrific things to their young sons. Good riddance, I thought, as jurors sentenced him to death. I had switched sides and now favored the death penalty.

In 1983, still on the pro-capital-punishment side of the issue, I wrote a newspaper series about the death penalty in California. I traveled to San Quentin and peered into the gas chamber. I met face-to-face with a death-row inmate and solicited letters from condemned men, whose scrawled missives were filled with misspellings and mangled grammar and reeked of self-pity. Astoundinglyconsidering that I was an avowed feminist and later chose to research and write on condemned womenit never occurred to me to ponder whether women had been executed in California. I also never questioned whether innocent people had been executed. Virtually all of my condemned correspondents claimed they had been framed. Had any of them been?

Neither omission seems surprising in retrospect. In 1983 there were no women on death row, and no one had been executed in California for nearly two decades. With a state supreme court that consistently overturned death sentences, it seemed unlikely that an execution would occur anytime soon. In fact, it took another nine years and a conservative resurgence for the state to resume executions. By 1992, when Robert Alton Harris became the first person executed in California in twenty-five years, my support for capital punishment had begun to waver. Harris, like Bonin, had been thoroughly despicable. He had managed to live fourteen years longer than the two teenaged boys he had kidnapped and shot in the back. And yet something seemed wrong with a system in which dozens of journalists clamored for credentials to watch a mans death while a San Francisco television stationunsuccessfully, as it turned outsought a court order enabling it to broadcast the event to an audience of millions.

For me, the death penalty existed largely as an abstraction until 2002, when I began research for a book on Nellie Madison, the first woman on death row in California. I knew by then that the state had executed four women. Madison was not among them. The fact that she had escaped the ultimate punishment seemed to border on miraculous. She had gone on trial in June 1934, charged with murdering her husband. Charles Fricke, the judge who later presided over the trials of Barbara Graham and Caryl Chessman, had presided in Madisons case as well.

Fricke had clearly favored the prosecution, going so far as to take the stand as a prosecution witness. Madisons attorney bordered on incompetent, yet appellate justices were willing to overlook egregious legal shenanigans in order to uphold her death sentence. Only a last-minute grassroots movement, fueled by revelations of extreme physical and psychological abuse on the part of Eric Madison, saved Nellie Madisons life. The governor reprieved her, literally days before her execution. This introduction to the bizarre and labyrinthine politics of capital punishment tipped me toward the abolitionists side of the argument. I have remained there ever since.

By 2006 I was reading books on death-penalty cases and following debates on blogs and elsewhere about the capricious, arbitrary, and inequitable nature of capital trials. I decided to enter the discussion by choosing an executed woman and writing about her. Enter Barbara Graham, arguably Californias most famous executed individual, male or female. Examining Grahams life, trial, appeal, and execution revealed just how easily police and prosecutorswith help from publicity-seeking judges and stool-pigeon conspirators promised immunity from prosecutioncould rig the process. Grahams case also revealed the role of the media in shaping perceptions of guilt and innocence. Was she guilty? It is impossible to know with any degree of certainty. But she was condemned following a grossly unfair trial. That alone should have earned her a reprieve from death.

Grahams case also raised an issue that has been virtually ignored in all of the public hand wringing about capital punishment. Proponents argue that execution brings a sense of closure to the families and friends of victims. What about the families of the executed? I thought of this frequently while writing this book. Barbara Graham had three young sons when she died in 1955. She fervently hoped, she said just before her death, that they would never know what happened to her. She could not have foreseen just how long her story would remain in the public realmin film, books, proposed legislation, even in songmaking it all but impossible for her children to remain ignorant of her fate.

This book is dedicated to the children of Americas executed men and women. They were victims too.

Introduction

HER GIVEN NAME was Barbara Elaine Ford, but her friends called her Bonnie right up to the end, when she walked into the gas chamber at San Quentin. It was 11:31 a.m. on June 3, 1955. By then the world knew her by another name: Barbara Graham. It knew that she was the third woman executed by the State of California, and by far the prettiest and the youngest. It knew that she dressed carefully for the occasion, wore a mask, and received two last-minute stays. The world also knew that it had taken her eight minutes to die.

Just shy of her thirty-second birthday, Graham had left behind a mess of a life. She had married four men. She had borne three sons. All of her sons lived with other people, and she had not seen the older two for several years. She had been in and out of trouble since her early teens, and her rap sheet spanned much of California. Most of her arrests were for misdemeanors, but she spent nearly a year in San Francisco County Jail for perjury.

The final arrest did her in. Los Angeles police picked up Graham and two men, Emmett Perkins and John Santo, on May 4, 1953, and charged them with murder in connection with a robbery gone wrong. Reporters and photographers quickly leapt on the story. They virtually ignored Perkins and Santo, both violent career criminals, but clamored for access to the woman they dubbed Bloody Babs and the Titian-Haired Murderer.

Next page