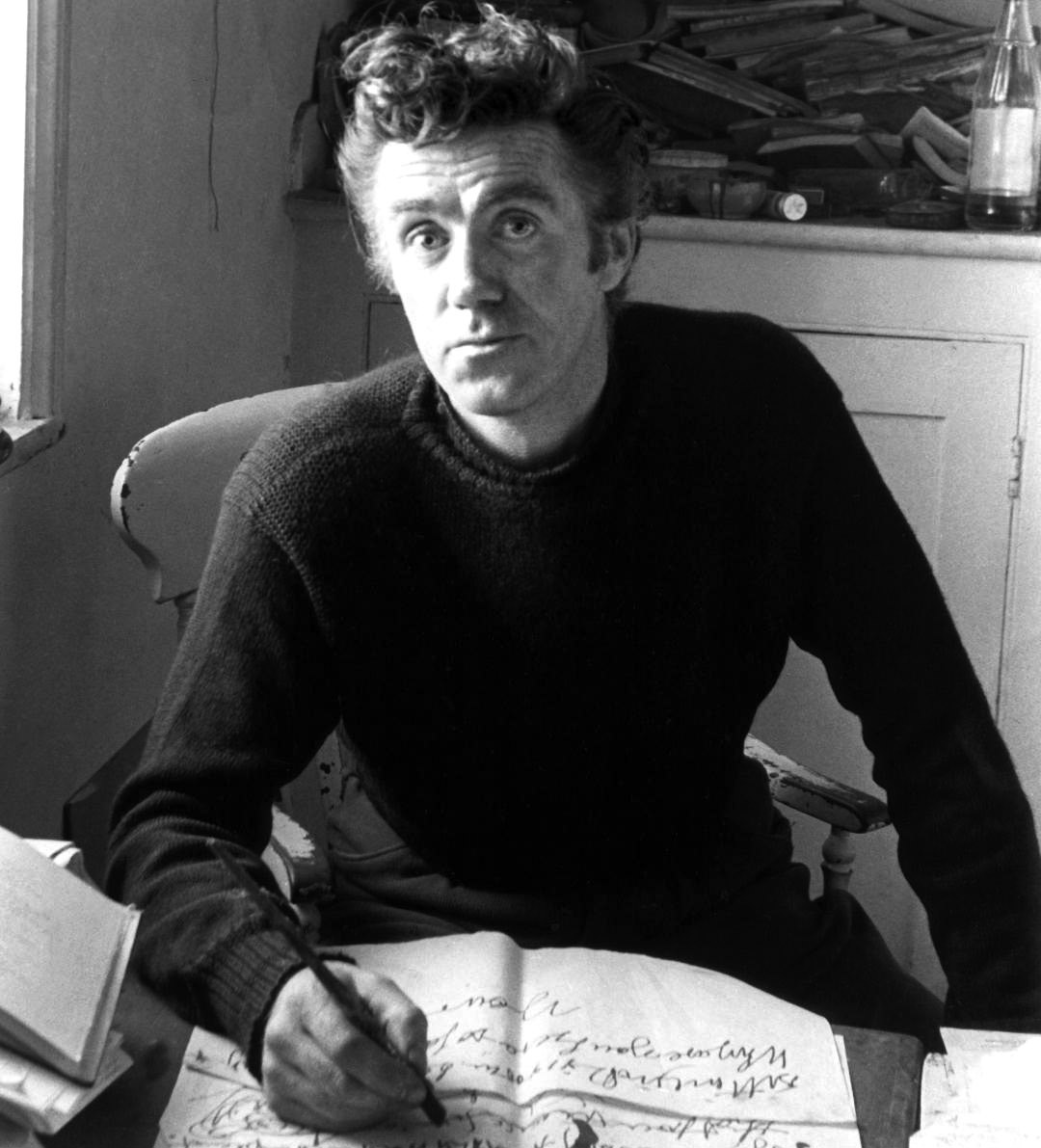

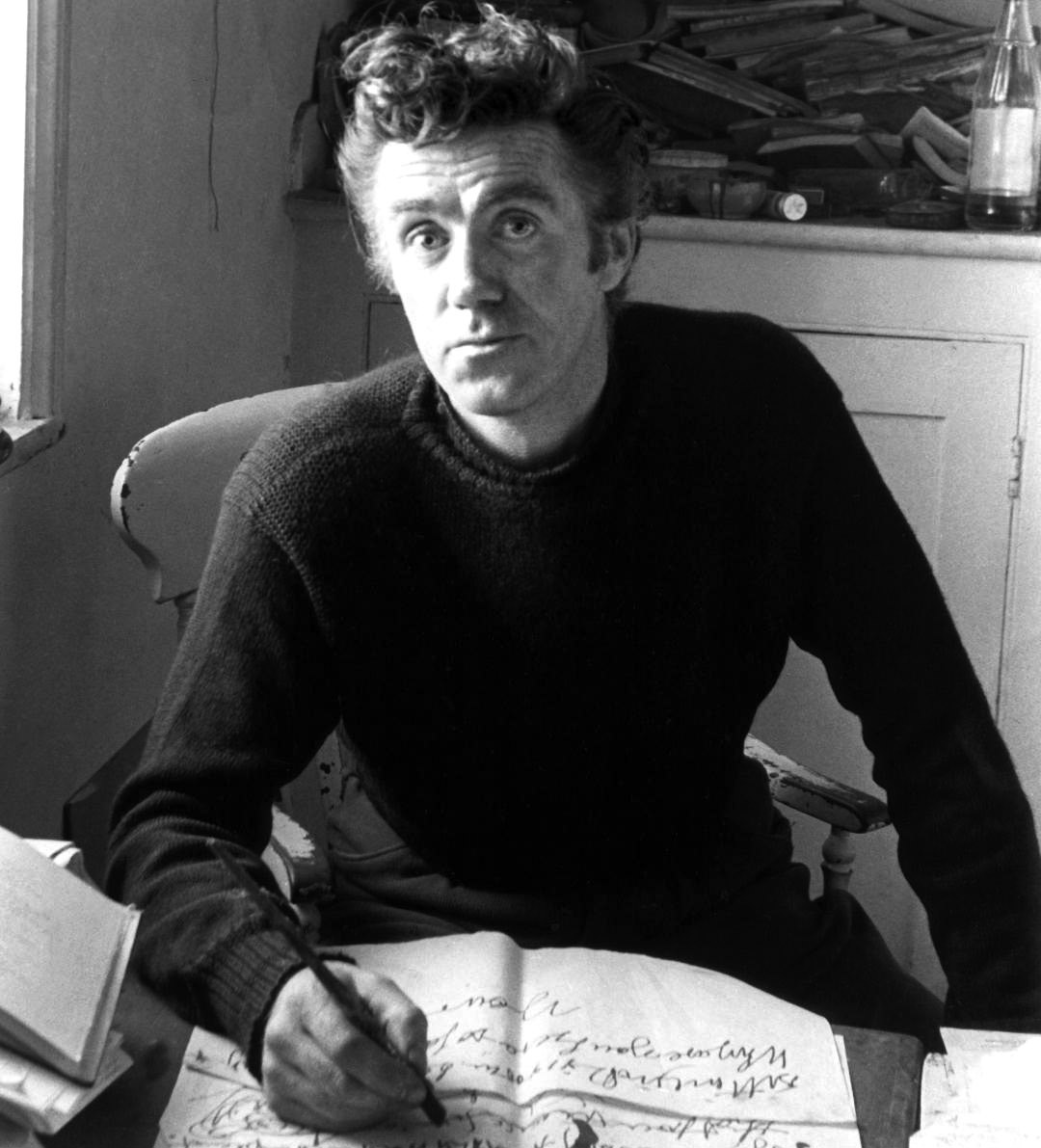

Photograph by Michael Seward Snow, late 1950s; the Estate of Michael Seward Snow / National Portrait Gallery, London W ILLIAM S YDNEY G RAHAM (19181986) was born into a working-class family in Greenock, Scotland, where his father worked as a shipbuilder. Graham studied structural engineering in Glasgow and philosophy and literature at Newbattle Abbey College outside of Edinburgh before publishing his first collection of poetry,

Cage Without Grievance, in 1942. In 1947, he received the Rockefeller Foundations Atlantic Award for Literature and lectured at New York University for a year. Upon returning to the UK, he lived briefly in London, where he met T. S. Eliot, who accepted Grahams fourth collection,

The White Threshold, for publication by Faber and Faber in 1949.

Shortly after, Graham moved to Cornwall where, with Agnes Nessie Dunsmuir, whom he married in 1954, he lived in a small village and often in great poverty for the rest of his life. A fifth book of poems, The Nightfishing, appeared in 1955; a sixth, Malcolm Mooneys Land, in 1970. Aimed at Nobody was published posthumously by Faber and Faber in 1993. In 2018, the centenary of Grahams birth was marked by the unveiling of a memorial stone outside the Writers Museum in Edinburgh. M ICHAEL H OFMANN is a German-born, British-educated poet and translator. He is the author of two books of essays and five books of poems, most recently One Lark, One Horse.

Among his translations are plays by Bertolt Brecht and Patrick Sskind; the selected poems of Durs Grnbein and Gottfried Benn; and novels and stories by, among others, Franz Kafka; Peter Stamm; his father, Gert Hofmann; and fourteen books by Joseph Roth. He has translated several books for NYRB Classics, including Alfred Dblins Berlin Alexanderplatz, Jakob Wassermanns My Marriage, and Gert Ledigs Stalin Front and edited The Voyage That Never Ends, an anthology of writing by Malcolm Lowry. He teaches in the English Department at the University of Florida. W. S. Graham SELECTED BY MICHAEL HOFMANN

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2018 by NYREV, Inc.

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2018 by NYREV, Inc.

Poems copyright the Estate of W. S. Graham Introduction copyright 2018 by Michael Hofmann All rights reserved. Cover design by Emily Singer A catalog record for this book is available from The Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-68137-277-8 v1.0 For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Contents

INTRODUCTION

T HE SCOTTISH POET W. S.

GrahamSydney Graham, but also Troubleyouas Greyhim, Double Yes Gee, and Sadknee Graham (he had a patella removed when he fell twenty feet onto concrete, but strangely the drunken accident only happened after the sobriquet), also via Jock (the generic name for a Scotsman) Graham, Joke Grim, and numerous other variantswas born a hundred years ago in 1918 and died in 1986. He led the kind of immemorially unworldly poets life that poetry, now tenured and professionalized, falls away from at its peril. The poet or painter steers his life to maim // Himself somehow for the job, is how Graham puts it in The Thermal Stair. One of Grahams most passionate and prominent supporters was Harold Pinter. I first read a W. S.

Graham poem in 1949, he writes on the jacket of the Collected Poems. It sent a shiver down my spine. Forty-five years later nothing has changed. They are the oddest of pairings, but yet it makes fascinating sense. Both are their own creations. There is Pinter, liberator of undertones inespecially BritishEnglish, of sinister aggression and hatreds, and Graham, who dwells in pleasantness and eerie brusqueness, who talks to himself as I suspect no one, not even Yeats, has ever talked to himself, and who creates in words gossamer, almost theoretical attachments to the absent, the sleeping, the dead, the speechless.

The reader. It is almost Jekyll and Hyde. But none the less persuasive for that. Pinter puts in an appearance towards the end of the wonderful book The Nightfisherman: Selected Letters of W. S. Graham (edited by Michael and Margaret Snow), as an admirer of Grahams work, as a public reader and supporter of it, and as a private patron.

God knows Graham needed him, or needed such a figure; his life was one of the most poverty-stricken of any of the great twentieth-century British poets. First and foremost, the letters read as a chronicle of this poverty and its effectand, indeed, lack of effecton the man who so unquestioningly bore it. Who sought to avoid, if at all and for as long as possible, that demon regular employment. Maim and shame. Near the beginning we find Graham in Cornwall. It is 1943, and he is twenty-five.

He has an ulcer and doesnt have to serve: Its raining now on the roof. Im living in a caravan a friends lent me in Cornwall, lonely and by the sea. I fish and gather mushrooms and write and cook. He was to stay, under only slowly evolving circumstances, for over forty years. The caravan is referred to as the wheelhouse or my poor arkvan. A sheeps head will make soup.

Tea, left in the pot until it is stewed, likewise, though not in a good way. Finding a usable lemon on the beach rates a couple of mentions. Soon Ill be able to get seagulls eggs, wonderful for omelettes. He tries ferreting to catch rabbits, but without much success. He writes to friendsoften the painters John Minton or Bryan Wynterto borrow money or to discuss the modalities of its repayment. I am completely broke just now and the people I might borrow from are also broke.

The sums involved are often tiny, a few pounds or even shillings, and it is an indication of his poverty that he is sometimes driven to ask for them at some specified future date, to be certain that they will be spent on whatever thing he has in mind, often bills or medicine. (If they came any earlier, they would just be spent.) He seems always to be cheerful; he is, after all, at some level, living the sort of uncompromised life he wants. Im writing every day and the good weathers begun and we have a goat. Thats some sentence. To go to London or Scotland, he has to hitchhike. He is in want of razor blades.

He asks friends for old boots and cast-off clothes. They move to a condemned coast-guard house on the rough north coast of Cornwall. He goes out with the fishermen sometimes, does occasional stints in bad weather in the lighthouse at Gurnards Head nearby. I measure out my life in paraffin gallons, this T. S. Eliotpublished poet writes in 1958, when he is forty and the author of five books.

For fifteen years after The Nightfishing (1955), he published none. A visitor records: We lived on flour-and-water pancakes cooked on a primus stove, and, when the paraffin was finished, over a driftwood fire. Sydney and Nessie [Dunsmuir, his wife] also used to collect limpets [mussels?] off the rocks and cook them, but only the cat would eat them, and even then not always. Graham twice went to the States briefly to read or teach (I am even homesick for

Photograph by Michael Seward Snow, late 1950s; the Estate of Michael Seward Snow / National Portrait Gallery, London W ILLIAM S YDNEY G RAHAM (19181986) was born into a working-class family in Greenock, Scotland, where his father worked as a shipbuilder. Graham studied structural engineering in Glasgow and philosophy and literature at Newbattle Abbey College outside of Edinburgh before publishing his first collection of poetry, Cage Without Grievance, in 1942. In 1947, he received the Rockefeller Foundations Atlantic Award for Literature and lectured at New York University for a year. Upon returning to the UK, he lived briefly in London, where he met T. S. Eliot, who accepted Grahams fourth collection, The White Threshold, for publication by Faber and Faber in 1949.

Photograph by Michael Seward Snow, late 1950s; the Estate of Michael Seward Snow / National Portrait Gallery, London W ILLIAM S YDNEY G RAHAM (19181986) was born into a working-class family in Greenock, Scotland, where his father worked as a shipbuilder. Graham studied structural engineering in Glasgow and philosophy and literature at Newbattle Abbey College outside of Edinburgh before publishing his first collection of poetry, Cage Without Grievance, in 1942. In 1947, he received the Rockefeller Foundations Atlantic Award for Literature and lectured at New York University for a year. Upon returning to the UK, he lived briefly in London, where he met T. S. Eliot, who accepted Grahams fourth collection, The White Threshold, for publication by Faber and Faber in 1949.

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2018 by NYREV, Inc.

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2018 by NYREV, Inc.