Praise for Rising Ground

Superb.Robert MacFarlane, Guardian, Book of the Year

Intriguing.Tom Robbins, Financial Times, Book of the Year

A fascinating study of place and its meaning.Justin Cartwright, Observer, Book of the Year

Pitch-perfect proseTom Adair, Scotsman, Book of the Year

Fascinating and hauntingly evocative.... A truly wonderful and enjoyable book.Jan Morris, Literary Review

Marsdens writing is just so good. Short, pacey chapters and an intimate and aphoristic style complement his powerful evocation of different terrains.Guardian

Marsden writes with charm and passion.... Vivid epiphanies are scattered throughout the text. Rising Ground wears its philosophy lightly and informs as it entertains. It is beautifully written, and a labour of love.Times Literary Supplement

A deft and compelling blend of cultural history, travelogue and observation.Daily Telegraph

The beauty of Marsdens book is that, although it is thoroughly researched and rigorously argued, it comes across as the result of experience, the close frequenting of that characterful region.... The extraordinary richness of daily perceptions and antiquarian knowledge assembled in Rising Ground never feels like a tray of specimens laid out for inspection.London Review of Books

It is Marsdens close attention to the immediacy of his experiencethe shape of the particular hill, the sound of the curlews cry in the early hours, the feel of heather crunching beneath his feetthat keeps him, and us, interested in this journey.Financial Times

A wonderful topographical history of the West Country but also a great essay on why some places exert such a psychological pull on us.Wanderlust

Every rock, hill and cliff holds a tale or a legend, and Rising Ground shows that such landscapes are not just close to our hearts but are a crucial part of our culture too.Geographical Magazine

Marsdens often solo walk is described in such evocative detail readers can envisage the rough Cornish landscape without previous knowledge of it. His probing yet conversational style is both informative and entertaining.Irish Examiner

One of those literary wonders that achieves many things.... It is, in one sense, a personal, profound book about the nature of belonging and mans desire to lay down roots and explore his surroundings. It is also a book that beautifully and succinctly evokes those surroundings... (and often with a refreshing sense of fun).Country and Town House

RISING GROUND

A Search for the Spirit of Place

Philip Marsden

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

Chicago

PHILIP MARSDEN is the award-winning author of a number of works of fiction, nonfiction, and travel writing, including The Levelling Sea, The Spirit-Wrestlers, and The Bronski House.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

2014 by Philip Marsden

Originally published in English by Granta Publications under the title Rising Ground copyright Philip Marsden 2014

First published in Great Britain by Granta Books 2014

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-36609-8 (CLOTH)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-36612-8 (E-BOOK)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226366128.001.0001

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Marsden, Philip, 1961 author.

Rising ground : a search for the spirit of place / Philip Marsden.

pages cm

First published in Great Britain by Granta Books 2015

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-36609-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-36612-8 (e-book)

1. Historic sitesEnglandCornwall (County) 2. Cornwall (England : County)Description and travel. 3. Cornwall (England : County)Antiquities. I. Title.

DA670.C8M34 2016

942.3'7--dc23

2015034535

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (PERMANENCE OF PAPER).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (PERMANENCE OF PAPER).

To

T. C. M-S.

R. F. H.

and

In memory of D. B. H. 19351998

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PART I

MENDIP

Mendeppe (1185): possibly from Celtic monith, mountain or hill, and Old English -yppe, upland or plateau, or from Brythonic mened, with an Anglo-Saxon suffix -hop, valley. A Basque origin has also been suggested, from mendi, mountain.

IN THE VILLAGE WHERE I grew up, on the edge of the Mendip Hills, a lane ran up from the church and near the top, it forked. One way curved back into the valley while the other, following the slope, continued upwards. That was the way we always took. The tarmac began to fracture, revealing polished knuckles of bedrock, and then that track too dropped down the hill and a smaller path broke from it, pushing up through the edge of a wood, to emerge quite suddenly into open ground.

Years later, I can recall with absolute clarity that moment and the sight which always stopped us dead: the miles of bracken stretching away to the south, rising and falling like sea-swells. No building broke that open arena; no cattle, no sheep and no fences. We never paused for long but hurried on to Long Rock a dragon-back ridge with its view over the Severn Estuary. Beyond it was a sweep of ground and chest-high ferns that ended with a group of yews. Their roots clawed over the edge of the rock and out into space. We lay on our stomachs and looked down into the gorge, and every now and then, far below, a car would beetle its way along the bottom. The opposite side was scattered with scrub. It was wooded in parts and in others, where it steepened, was covered in rocky scrub and scree. At the top, the land opened out again, and we knew that place as well, with its woods off to one side, and a plantation beyond but everywhere else just open ground; as you climbed the central ride and saw the skyline ahead, wide and flat beneath the clouds, you felt certain that you could carry on that way for ever.

On to these blank places known only as the hill and the combe I sketched the map of my childhood. It proved an endlessly supple backdrop to the daydreams of a seven-year-old, or the broodings of a fourteen-year-old. I spent days up there sometimes with my brother, sometimes with friends, sometimes alone.

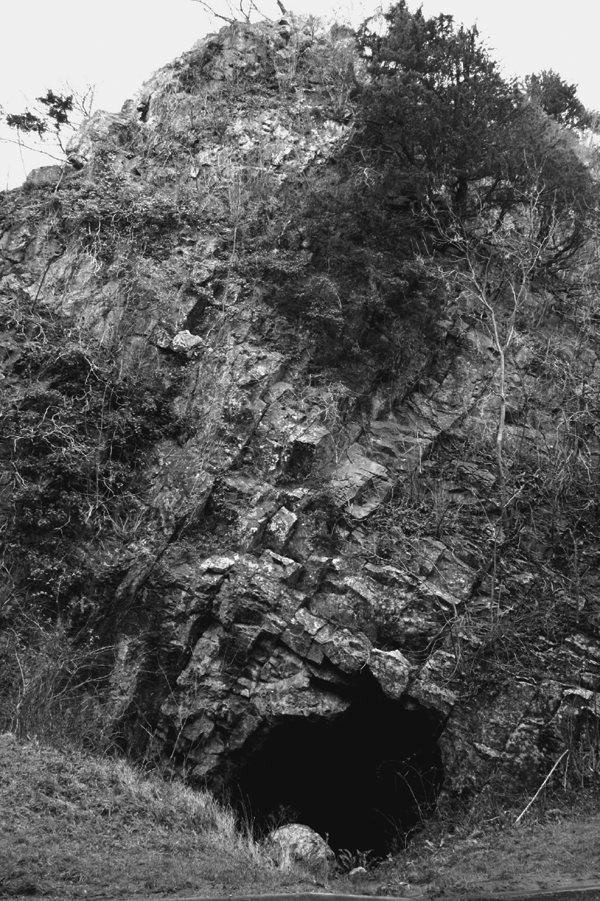

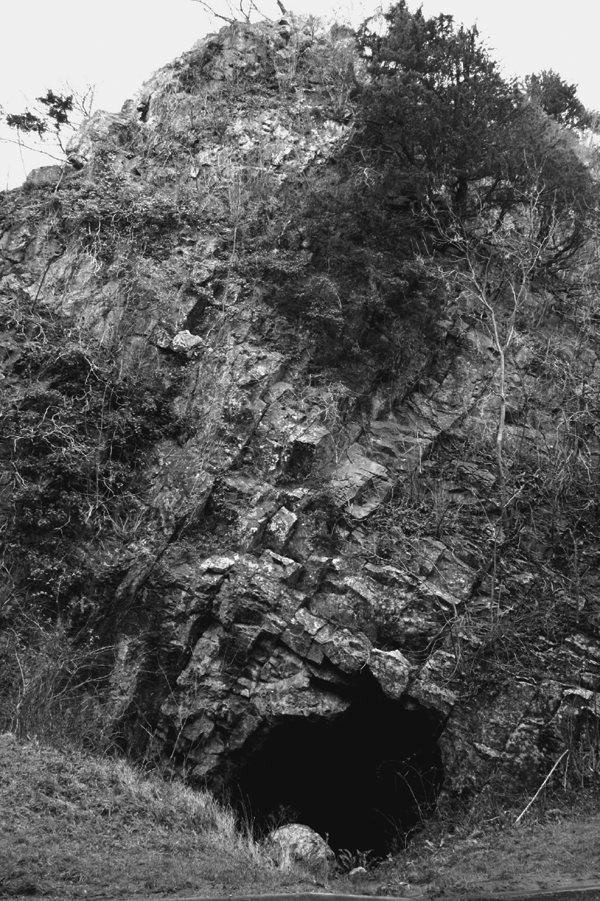

It was limestone country, so there were caves. On the hill they were called swallets: sudden pits that looked like outsize basins, dropping to plug-holes that we tried to squeeze into but never dared go far. Down in the gorge was a proper cave called Avelines Hole. The entrance opened at the base of the cliffs like a giants mouth. We stood outside, then went in a few steps, then further as the years passed, breathing the stale air, sliding on the buttery mud. The tunnel was neither a walk nor a climb but something in between, a slant down into the gloom. But it went nowhere, tapering like a sock to a damp and rocky end. Lots of things were like that: they seemed exciting to begin with but then they just ran out.

Later when we went potholing, with lamps and helmets and ropes, the ways in were much more furtive. Often they seemed to be in a bush. But they opened up labyrinths of tunnels and chimneys and grottos. Now, with real caves to explore, we walked past Avelines Hole with hardly a glance. I loved the strangeness of those potholes. They might lead us up and down again by a completely different way, spilling us back into daylight in a different place. Yet in the end the potholing stopped. I think I preferred it out on top, with distance everywhere and the sky.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (PERMANENCE OF PAPER).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (PERMANENCE OF PAPER).