Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my thanks for their help in making this anthology happen to Sandra Wake, Tom Branton and Oliver Holden-Rea of Plexus Publishing; Sarah Lowe of Fifth Avenue PR; Zoe Miller of Mute Records; Bleddyn Butcher for both his wonderful photographs and lively conversations over three decades concerning the subject of this book; needless to say every writer represented here, for many of whom I entertain the warmest feelings of personal affection; plus The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph and Word magazine with whose kind permission three pieces here are republished. And, of course, I would like to thank every musician in the Nick Cave orbit who has talked to me over the years, and finally the man himself; I hope he might find this selection of pieces offers a fair if not always adulatory chronicle of how his life and work has been reflected by others.

Acknowledgement is hereby made to the following for permission:

A Boy Next Door by Michel Faber, Rocks Backpages, August 2002. 2002 by Michel Faber. Sometimes Pleasure Heads Must Burn A Manhattan Melodrama by Barney Hoskyns, New Musical Express, 17 October 1981 (Rocks Backpages). 1981 by Barney Hoskyns. A Man Called Horse by Antonella Gambotto, ZigZag, January 1985 (Rocks Backpages). Copyright 1985 by Antonella Gambotto. Prick Me Do I Not Bleed? by Mat Snow, New Musical Express, August 23 1986 (Rocks Backpages). Copyright 1986 by Mat Snow. Of Misogyny, Murder and Melancholy: Meeting Nick Cave by Simon Reynolds, National Student, 1987 (Rocks Backpages). Copyright 1987 by Simon Reynolds. The Needle and the Damage Done by Jack Barron, New Musical Express, 13 August 1988 (Rocks Backpages). Copyright 1988 by Jack Barron. Edge of Darkness by Nick Kent, The Face, December 1988. Copyright 1988 by Nick Kent. Nick Cave on 57th Street: A Late 80s Memoir by Kris Needs, Graffiti, 1988, Remixed with additional material 2009. Copyright 1988, 2009 by Kris Needs. Titter Ye Not by Andy Gill, Q, May 1992 (Rocks Backpages). Copyright 1992 by Andy Gill. The Return of the Saint by James McNair, Mojo, March 1997. Copyright 1997 by James McNair. From Her to Maturity by Jennifer Nine, Melody Maker, May 1997. Copyright 1997 by Jennifer Nine. The New Romantic by Ginny Dougary, The Times, 27 March 1999. Copyright 1999 by Ginny Dougary. Let There Be Light by Jessamy Calkin, The Daily Telegraph, 17 March 2001. Copyright 2001 by Jessamy Calkin. Used with the kind permission of The Daily Telegraph. Nick Cave: Renaissance Man by Robert Sandall, The Word, March 2003. Copyright 2003 by Robert Sandall. Used with the kind permission of The Word. Nick Cave: The Songwriter Speaks by Debbie Kruger, Expanded chapter from Songwriters Speak, 2005. Copyright 2005 by Debbie Kruger. Old Saint Nick by Barney Hoskyns, Expanded from Dazed & Confused, October 2004. Copyright 2004 by Barney Hoskyns. Nick Cave: Raw and Uncut 1 by Phil Sutcliffe, Interview transcript for a Mojo feature, 21 October, 2004. Copyright 2004 by Phil Sutcliffe. Acropolis Now! by Michael Odell, Q, March 2005. Copyright 2005 by Michael Odell. Old Nick by Simon Hattenstone, The Guardian, 23 February 2008. Copyright 2008 by Simon Hattenstone. Used with the kind permission of The Guardian.Nick Cave: Raw and Uncut 2 by Phil Sutcliffe, Interview transcript for a Mojo feature, 25 November 2008. Copyright 2008 by Phil Sutcliffe.

Contents

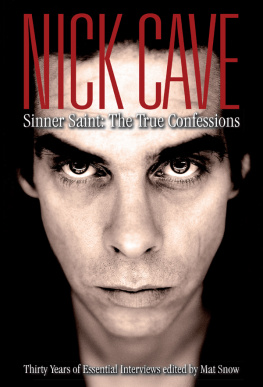

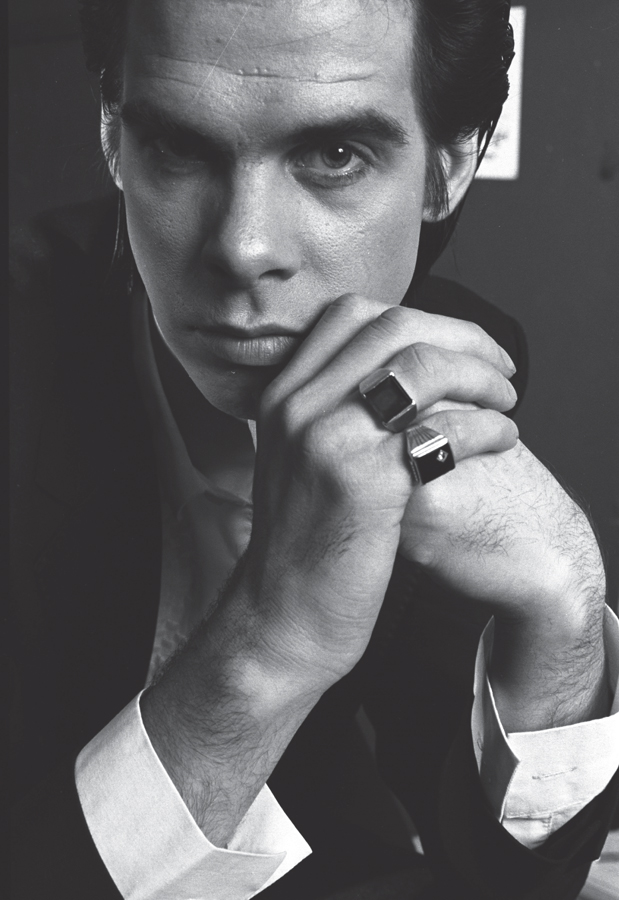

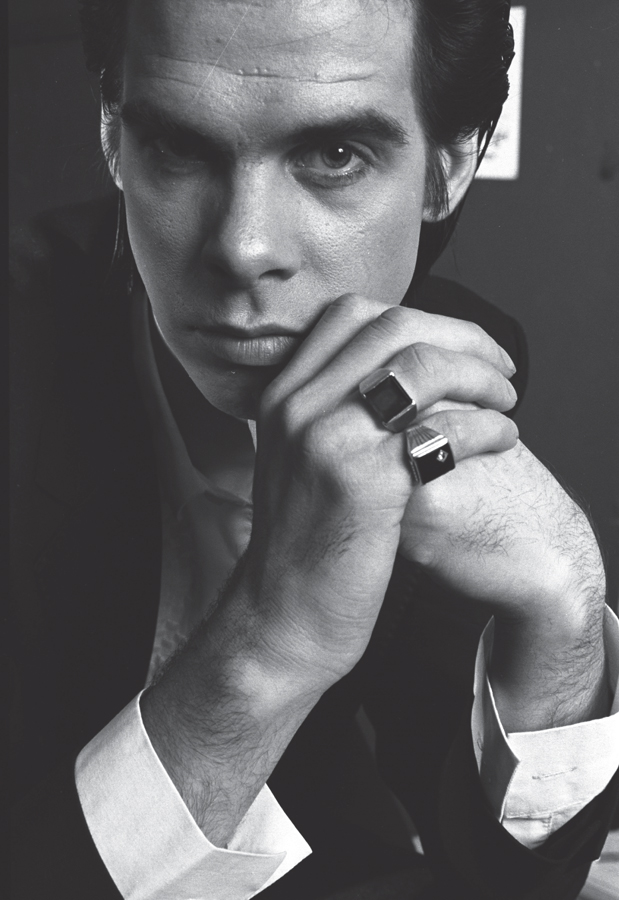

Nick Cave at Beehive Studios in Chalk Farm, London, 5 December 1988.

Foreword

Mat Snow

N ick Cave: Man or Myth?

On New Years Eve, 1983/4, Nick Cave played the Seaview Ballroom in St Kilda, Melbourne, under the heading of that rhetorical question. The Birthday Party, of which he had been the singer and lyricist, had ceased trading six months before, and from its remnants his new, more fluid backing group the Bad Seeds would be christened five months later.

Its a teasing self-advertisement from a man who has always had an instinct for the telling phrase.

More than that, though, its a family in-joke and a message to the other side.

Seven years before, Nick Caves father, Colin, was killed in a car crash, the news reaching the nineteen-year-old while he was being bailed out of police custody and not for the first time by his mother. Father and son were at loggerheads, forever now unresolved and unreconciled. Father was a teacher, an academic, a man of high cultural seriousness, as so many Australians are, often to the amazement and mild awe of urbane Brits for whom all Aussies are Bondi Beach backpackers pulling pints in Earls Courts Kangaroo Alley. Loggerheads for the usual reasons the generation gap and the mismatch of paternal expectations with a son defining himself as different. The youngest of Dawn and Colin Caves three sons, Nick had been usurped as the baby of the family by his younger sister Julie; his new role in the sibling order would be problem child and rebel. What was he rebelling against? What have you got? How about the paradox that father chastised his third son as a rebel while devoting himself to a far greater rebel (and irritant to the police) in his paper titled Ned Kelly: Man or Myth?.

Well, dad, if only you could see me now.

Biographers are always looking for a key actually, the key: the character, incident or relationship behind the scenes that willy-nilly shapes and directs what the star presents on the public stage, even the need to be on that stage at all.

Nick Cave seems acutely aware of the springs of his artistic self, and over the years has hardly concealed the keys that turn his clockwork. Many artists will deny such keys, even to themselves. Not Nick Cave. His life and art have long meshed. At first it was as comically self-disgusted punk star braggadocio (take the Birthday Partys Nick the Stripper, a song presumably inspired, even sired by the Stooges I Wanna Be Your Dog). But over the next few years a complex mechanism of personal self-exploration and revelation have, I think, found expression in a growing repertoire of musical voices and song styles. These can be summarised deep breath as a Baudelairean angel/whore bipolar sexual obsessiveness rendered serio-comically in the idiom of the Deep South as it might have been stylised in the music theatre of Brecht and Weill.

An extensive aside here on Nick Caves rocknroll ancestry. He has owned up to many influences, ranging from Tom Jones to Jethro Tull, Alex Harvey to Van Morrison, Johnny Cash to the Stooges. Artists never mentioned include those so audibly influential that their omission in Nicks roll call of inspiration must be down either to amazing coincidence or else their presence hidden in the plain sight of music that everyone heard and knew the background noise of 70s teenhood.

First, the tense and doomy soundscape of Dazed and Confused by Led Zeppelin, from the groups 1969 debut album. Every teenage boy in the 70s knew Led Zep, even if only to repudiate them. I would find it hard to believe that this supercharged chestnut of dungeon bass and teenage bedroom air-guitar in particular failed to percolate into the budding Birthday Partys earshot.

Then, narrowing the focus of influence, the Doors. If bipolar Baudelairean sexual obsessiveness rendered in the idiom of the Deep South as it might have been stylised in the music theatre of Brecht and Weill is your bag, you could hardly avoid it in the six studio albums by the group before singer-lyricist Jim Morrisons death in 1971. If you were a rock fan at any time from 1967 onwards, you could hardly miss The Doors. Just two of their greatest hits, The End and Riders on the Storm, bear a striking ancestral likeness in their lyrical themes, imagery, personae, and mode of delivery, especially vocal, to such Cave classics as From Her to Eternity, Tupelo and The Good Son.

Next page