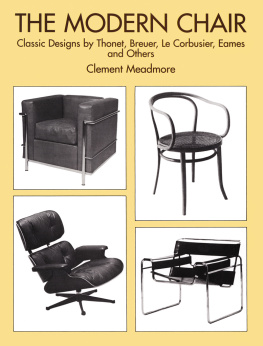

The Modern Chair

Classic Designs by Thonet, Breuer, Le Corbusier, Eames and Others

Clement Meadmore

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Copyright

Copyright 1974, 1997 by Clement Meadmore.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 1997, is an unabridged republication of the work as published by Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York, in 1979. A new preface by the author has been added. The work was originally published in 1974.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Meadmore, Clement.

The modern chair : classic designs by Thonet, Breuer, Le Corbusier, Eames, and others / Clement Meadmore.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1979.

Includes index.

eISBN 13: 978-0-48614-269-2

1. Chairs. 2. Chair design. I. Title.

TS886.5.C45M38 1997

749'.32-dc21 | 97-19699

CIP |

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

29807803

www.doverpublications.com

Introduction

The aim of this book is to show that certain chairs, through a combination of practical qualities and elegance, have transcended the confines of time and fashion. The sense in which each chair belongs to its period is not of primary interest to me here, and so I shall not take into account the art historians considerations of fashion. I shall show that though several of the chairs have marked connections with twentieth century movements in fine and applied art Constructivism and Art Nouveau, for example none of them, however radical its design is merely an exercise in a style imposed by contemporary taste. Each chair, then, has been selected for qualities that we can assess from our standpoint today; qualities which have less to do with style and period than with a solution of a defined problem. I have tried to explain each problem, and the consequent significance of the designers solution (bearing in mind the limitations imposed by techniques and materials available at the time) and to discuss its contemporary relevance.

The continued production of each chair will be justified on design alone. I do not feel that indiscriminate reproduction in any past style is justified, because I do not accept nostalgia as a legitimate reason for prolonging and extending the availability of any object through mass-production. When we decide to continue producing what is supposed to be a classic design, we should make sure that it really serves our needs today as it was first designed, and not in some up-dated, modified or improved form. If up-dating is needed, we are at the point of recognizing a new possibility and we would do better to create a new design. Some of the chairs here have undergone minor modifications, but the basic concept of the designer has not been altered, and in no way are the modifications parallel to the kind of production changes made upon antique originals by the mass-production hand-carved manufacturers.

The chairs selected are not all fully machine made, nor are they all made in quantity, but with only one exception they are all available in some form of current production. Certain designs, such as those of Breuer and Le Corbusier, have had a lapse between initial and revived production, and this fact may seem to disqualify them from the requirement of timelessness, but I believe that they will now be in production for many years. The lapse in the popularity of furniture designed by Breuer and others in the pre-war period was caused by an oversight on the part of those who decide what will sell (they must have been dismayed by the avant-garde nature of Bauhaus designs) and by the total disruption of the new trends that were then emerging in Europe, by the outbreak of the Second World War.

I have tried to avoid too much vague talk of aesthetics, but it is difficult not to retire into ones own aesthetic vocabulary when looking at these chairs. I am reminded of Van Doesbergs description of Rietvelds chairs: the abstract-real sculpture of our future interior. Some of the finer adjustments of proportion, left unresolved by the mere solving of functional problems, have often been made with a visual sensitivity which undoubtedly contributes to make a chair a delightful object, and to enhance its purely formal significance. It can even be said in some cases that visual considerations have led to fresh ideas, and have demanded the use of new materials and methods invention having perhaps been the mother of necessity.

Certain of these chairs are kept on the market by people who buy them for the name of their famous creator, or for the implication of design integrity they are thought to confer. I hope that perhaps a greater understanding of the chairs real qualities may make for a less precious attitude to good design, and for a less unquestioning acceptance of the statussymbol chair as a kind of stylistic name-dropping. More important, I hope that a real appreciation of these chairs will lead to a demand for new designs that are the result of genuine effort at a high creative level to solve the problems of chair design.

The scale drawings in this book are all one-eighth of full size, so that dimensions can be ascertained by direct measurement, and comparisons can be made at a constant scale.

Preface to the Dover Edition

The last chair in this book was designed in 1971 and just happens to be a prime example of the basic criteria for inclusion. I am still looking at chairs and still evaluating them in terms of problem solving. I must say it is not a very rewarding pursuit. In fact when I considered updating the book I realized that I could not think of a single chair to add. I still believe that a designer who is not solving problems is a stylist, and styling is what we have been looking at for the last quarter of the century. Perhaps the next century will present us with some new problems demanding new solutions.

Clement Meadmore 1997

Errata

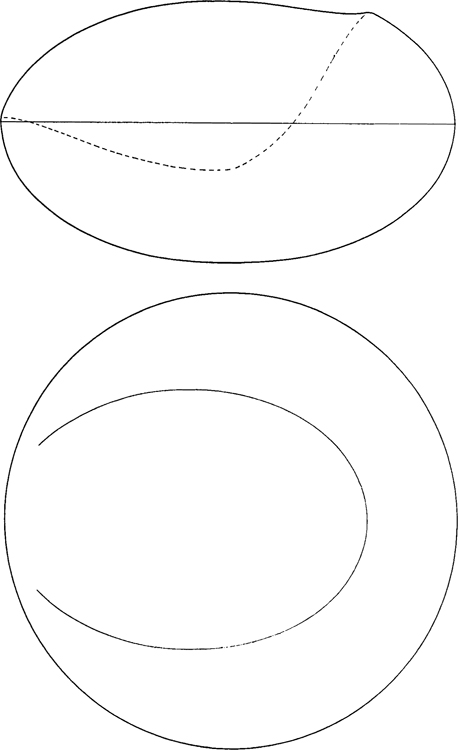

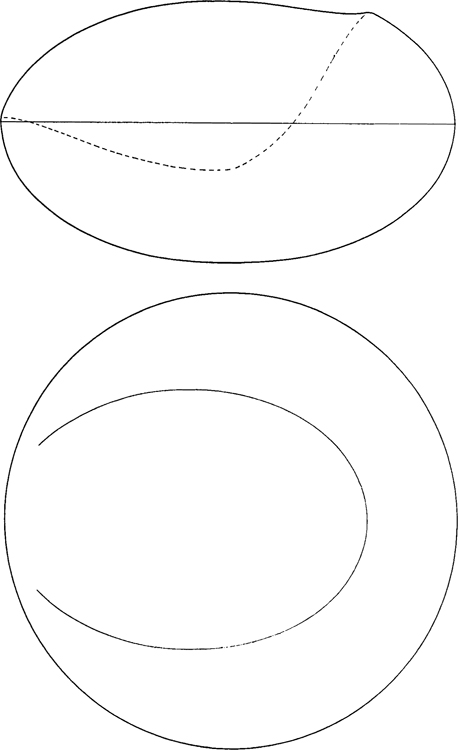

. Ignore indication of scale at top of page. As indicated above, all drawings in this book are one-eighth of full size.

.

[Above replaces diagrams on .]

Part 1 Classics

The classic chairs, for the purpose of this book, are those designed between the beginnings of the modern movement and the Second World War and which survive in production to the present day. Within this area I have selected those which I consider to be innovative and influential in a positive way. In most cases they were the first examples of what has now become a familiar type in the idiom of modern furniture.

I have included more than one example of cantilever chairs, partly because it is not absolutely clear which was the first of its kind, and because they each show significant differences, in rationale and aesthetic. Mies van der Rohe, for instance, thought of the cantilever primarily as a graceful spring, whereas Marcel Breuer saw it as a simplification of the old idea of four legs ().

The other classics included here nearly all show interesting affinities with contemporary fine art movements, showing the extent to which their designers were involved with painters, sculptors and industrial and graphic artists of their own time, Rietvelds chairs ().

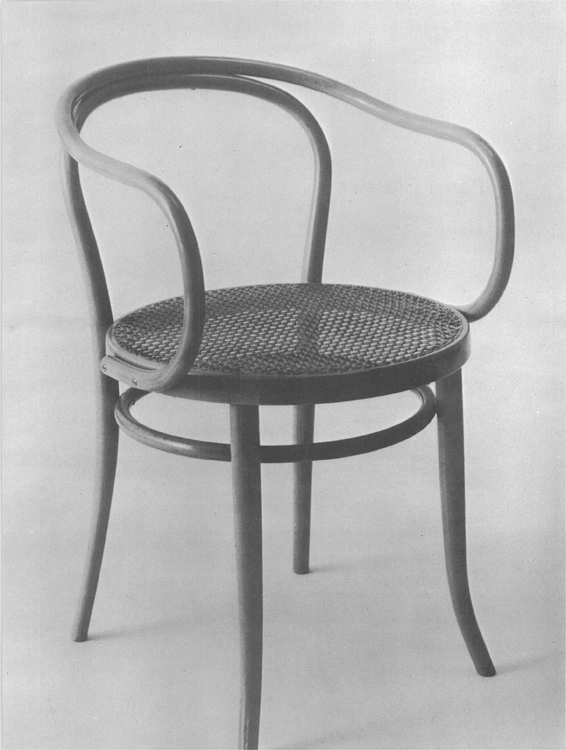

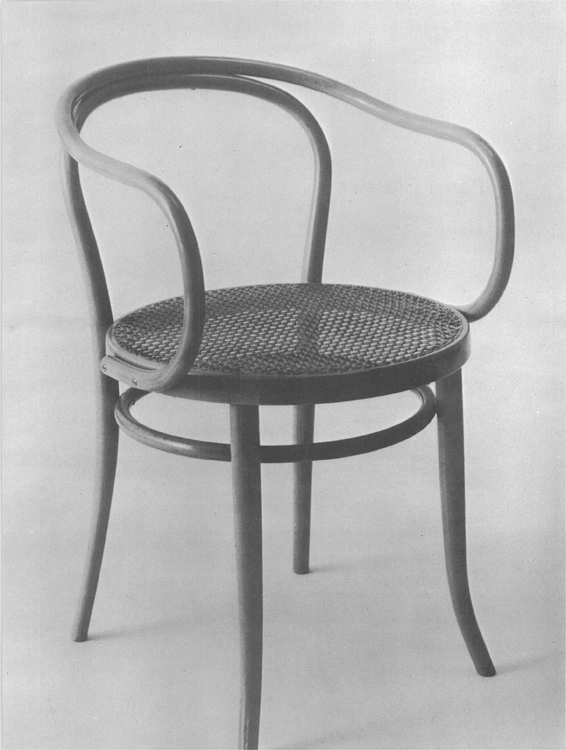

Bentwood armchair

Michael Thonet

Austria, 1870

In 1840 Michael Thonet invented a process for bending wood which revolutionized the mass production of furniture. He soon established a range of bentwood chairs and other furniture running into hundreds of variations, of which the example shown here is perhaps the most elegant. His patented process consisted of clamping a thin flexible strip of steel along one side of a piece of steamed wood. This side, after bending, became the outside of the curve. Without steel, compression of the inner edge and tension on the outer would result in the outside cracking on the curve. This simple process enabled Thonet to use extremely tight structural curves, just as strong or even stronger than the wood in its normal state before treatment. Another result was the elimination of virtually all complex jointing in the construction, as elements could be lapped over one another and joined with screws.

Next page