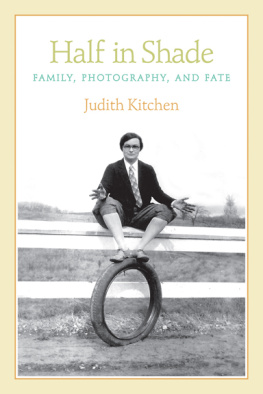

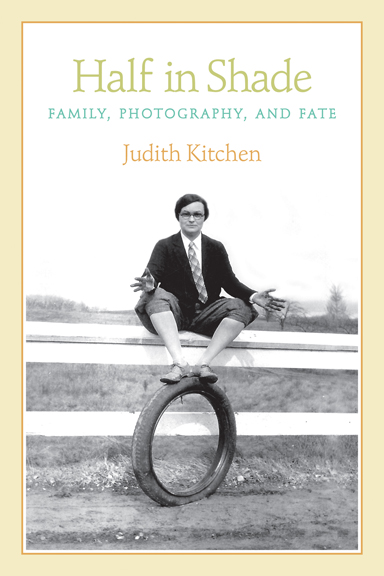

HALF IN SHADE

Half in Shade

FAMILY, PHOTOGRAPHY, AND FATE

Judith Kitchen

COPYRIGHT 2012 Judith Kitchen

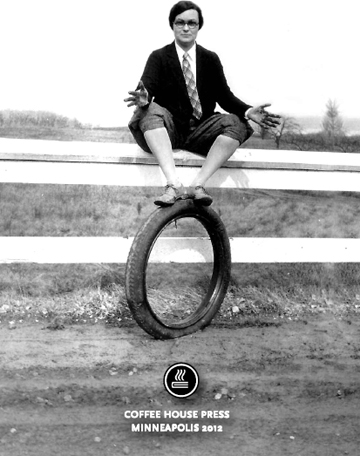

COVER & BOOK DESIGN Linda S. Koutsky

Coffee House Press books are available to the trade through our primary distributor, Consortium Book Sales & Distribution, .

Coffee House Press is a nonprofit literary publishing house. Support from private foundations, corporate giving programs, government programs, and generous individuals helps make the publication of our books possible. We gratefully acknowledge their support in detail in the back of this book.

Good books are brewing at coffeehousepress.org

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Kitchen, Judith.

Half in shade : family, photography, and fate / Judith Kitchen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-56689-296-4 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-56689-306-0 (ebook)

1. Kitchen, Judith.

2. Authors, American20th centuryBiography.

I. Title.

PS3561.I845Z46 2012

813.54DC23

[B]

2011030609

For the past

where we came from

For the future

Benjamin, Simon, Ian

Introduction

I HAVE NEVER OWNED A CAMERA and I never snap photos, except reluctantly when asked by others. I have always relied on memory to call up my personal images of the past. And so it was neither the curiosity of a photographer, nor some literary need to imagine visual images, that drew me to the haphazard collection of boxes and albums scattered on the bottom shelves, the ones my mother had managed to save from the floods. I dont remember anyone ever looking at them, and only later, when it was too late, did I wish I could question the photographers or their subjects. By then I realized I didnt know who they really werethese strangers we call familylost now, slipping into the shade. But I wasnt done with themor rather, they werent done with me. Their stern faces kept turning in my direction, asking me to bring them back to light.

I found myself feeling grateful to those who had captured these earlier generations for methe professionals who had posed them stiffly in their studios, and the amateurs who had caught them off guard in moments of frivolity. I became fascinated with the ghost in every photographthe unseen presence behind the lens whose eye shapes what, and how, we will see.

A photograph sparks reverie and speculation. No two viewers will see it exactly the same way. Theres something about the framing that makes us consider the presenceor absenceof an aesthetic. Snapshots, though, are somewhat exempt from artistic scrutiny. We note the composition, but we do not wonder about the use of negative space. Instead, we search out detail. Snapshots record a real, lived moment in time, lost the very second the shutter clicks.

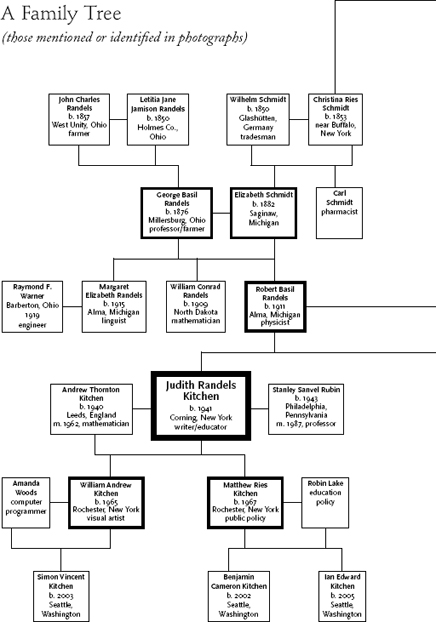

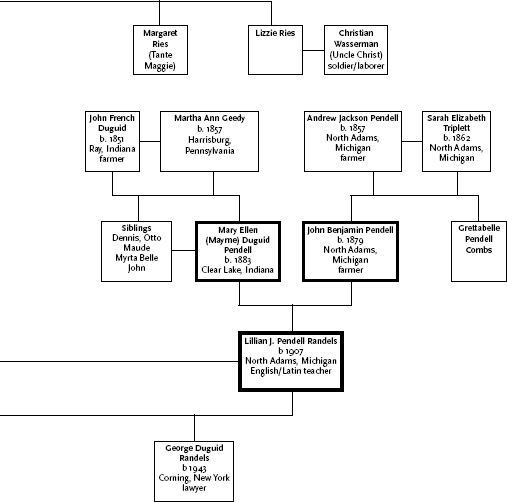

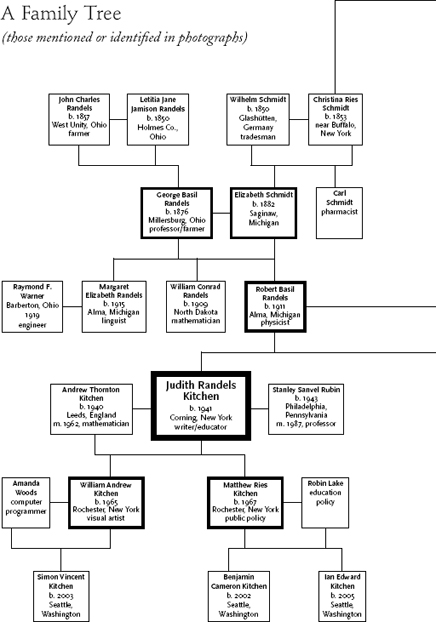

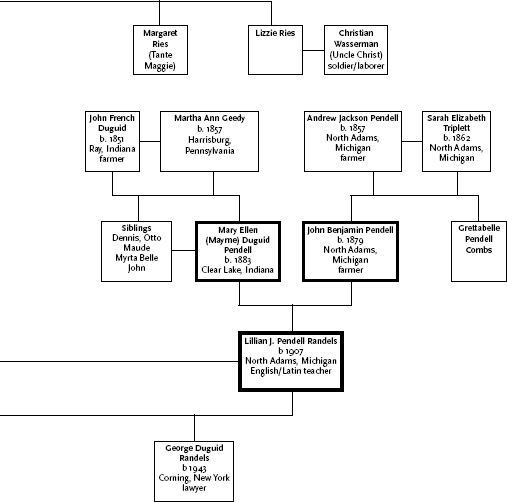

As I sifted through the rough black scrapbook pages and the newer thin plastic inserts, I had no idea what I would find, or what I hoped to discover. Of course I did find the usual sepia portraits, and the perfunctory snapshots of reunions, first days of school, and summer vacations. But among the predictable photos, I also came across playful moments, oddball scenes, remnants of a past that felt oddly contemporary. I had begun to play detective, digging into my treasure trove for clues. Often, I had no way to identify the subjects, and no one I could ask. What, for example, drove my mother, Lillian, to make her way so far from the farm where she grew up? Who was she, before she became merely my mother? How did my Aunt Margaret actually see her scar? Who were those people who crossed the ocean to build a new country? How did someone elses family photographs appear, as if by magic, on my disk?

In an era of so many moving images, there is a mystery in the stilled moment. The very black-and-white of it. It serves as entry into another time, another place. I wanted my words to set things in motion. Suddenlyas a writer, not just as a viewerI had a whole new set of questions. How to give voice to what is inherent in the visual? How to keep the visual from dominating, making all my thoughts redundant? I found myself experimenting with the placement of the photograph, investigating to see whenand howthe visual became integral and necessary. I used the snapshots as triggering devices, sometimes fixing on one, sometimes weaving them together, joining the generations, so to speak. I put people Id never seen next to ones I knew intimately. I let them speak to each other, and to me.

My challenge as a writer was not to describe, but to interact. Not to confirm, but to animate and resurrect. The past became my subject, and memory my lens. But memory was often insufficient. In order to insinuate myself into the personal lives of others, I frequently had to rely on probability, supposition, intuition, the half known, the partially knowable. Sometimes out of desperationor desireI resorted to fantasy.

I became aware of a kind of triangulation: me, the photograph, and its subject(s). From my temporal advantage, I found I could supply what my subjects would never knowthe future. I found myself in a kind of time warp in which I knew more than my subject, but less about my subject. My interest was not in uncovering a hidden narrative, or in enhancing a known story, or in revealing a specific character. I wanted to ponder how each individual life was/is framed by circumstance, how we are sometimes called to act, and sometimes merely to reflect.

In some way, snapshots are always retrospective. They take on new meanings as history unfolds. If it could be said that we measure time in warsCivil, World, Vietnamthen we bring to any photograph the shadow of before or after: Paris, 1938; Chicago, 1912; Edinburgh, 1964. Over and over, I found myself looking at faces that seemed so innocent. From my vantage in their future, I was able to sense what lay ahead of them. The older the photograph, the less I knew of its subject, but the more the photograph and subject seemed to step back in time, to fit itself into a larger, national history. I realized that, in many respects, the albums revealed patterns of American immigration and opportunities.

Then there were the words, also revelatory in their innocence: my grandfathers letters, my fathers fragmentary memoir, my mothers journal, brief glimpses of someone elses life on the backs of postcards or envelopes, and identifying notations on the photographs themselves. Handwriting so individual and intimate that reality commanded pride of place. These people lived, and the sum of their lives points directly to the precarious present.

Half in Shade was written over a ten-year period. But it took a serious illness to make me realize that, like the people in the snapshots, none of us knows what lies beyond the moment, outside the frame. Each of the books many sections is followed by a meditation on illness, as though to underscore our fragile ties. In writing about the uncertainties that had entered my own life, I came to understand that I was, in some way, taking my own photograph. Smile. Click. Okay, one more.

Judith Kitchen