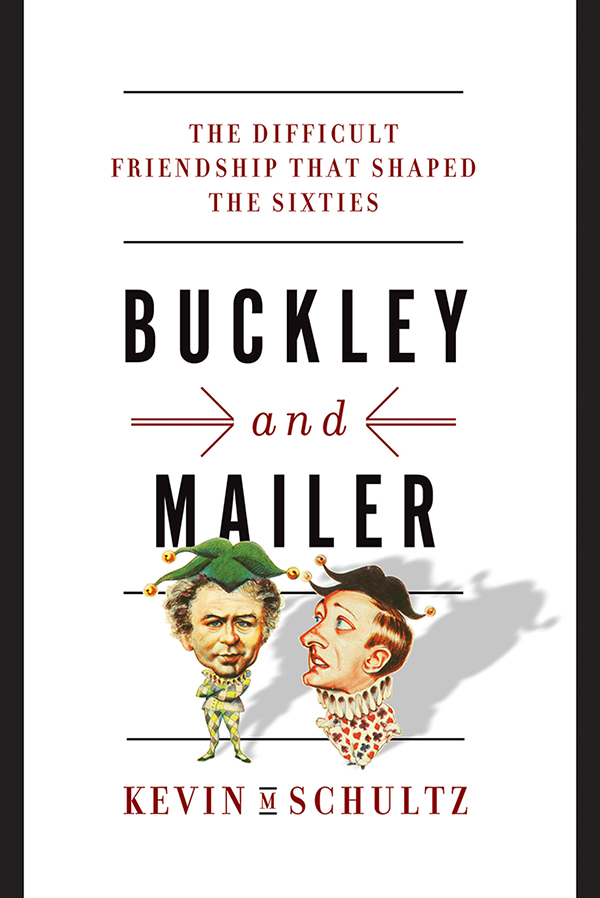

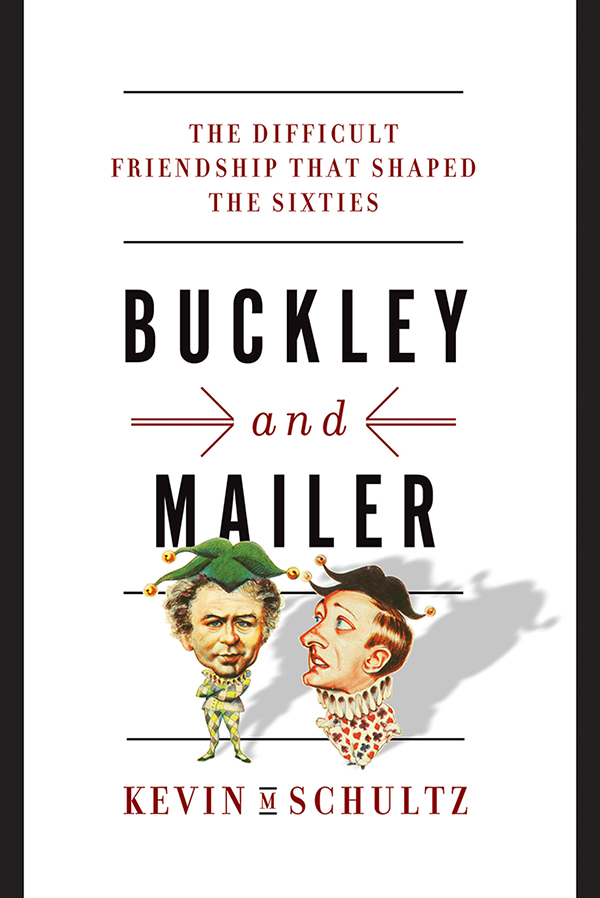

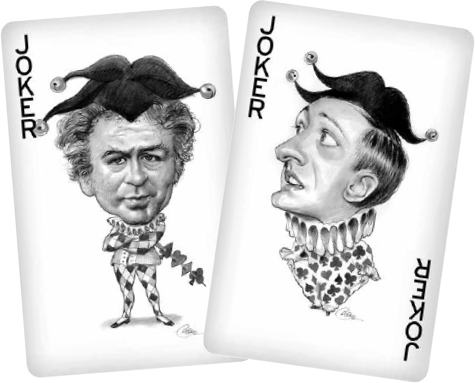

BUCKLEY

and

MAILER

The Difficult Friendship That Shaped the Sixties

KEVIN M. SCHULTZ

To Terra and the kids

Contents

PART I

DEBATING THE FUTURE (196263)

PART II

IMPREGNATING THE HOST (196465)

PART III

BIRTHING PANGS (196668)

PART IV

THE NEW ORDER (196976)

It is said of the Conservative that he wishes to protect the root; of the radical that he goes to the root. One maintains, the other explores. But in the same land. There is a dialogue possible between the conservative like Mr. Buckley and the radical like myself which could prove vastly more interesting than any confrontation between liberal and conservative, or radical and liberal.

Norman Mailer

BUCKLEY

and

MAILER

I t was late fall, and the old man awoke in a sour mood.

As he rolled out of bed, he saw the cold November winds outside and remembered it was only supposed to reach the mid-30s that day. He often woke up stiff anyway, earlier than he should, at hours that sometimes alarmed the help. He occasionally even showered and ordered breakfast at two oclock in the morning. The servants obeyed, for they loved the man. But they also gently reminded him it was well before sun-up. Did he really want his eggs? Okay, sir, okay.

Compounding the changing weather, he was also sick and dying, and he knew it. It might be days or weeks or months before the end came. God only hoped it wouldnt be years. So far, he had made it through emphysema, diabetes, sleep apnea, skin cancer, heart disease, near kidney failure, and various prostate afflictions. It was hard to argue that his bill of health didnt read like a medical encyclopedia cataloguing the degenerations of old age. The emphysema was progressive and incurable, too, and the heart disease could take him at any moment. He was sick and dying, and he knew it.

The most degrading part, though, wasnt confronting death per se but the measures they took to keep you alive. Most annoyingly, they had been monitoring the color of his urine, which vacillated from a deep rose color to a bright orange. There was a time when he could take for granted a normal yellow pee, when he felt at liberty to drop his trousers in the middle of New York City traffic and urinate out the door of his limousine. Some unsuspecting driver might have wondered, Was that William F. Buckley, Jr., who just peed on us from the left-hand turn lane of Riverside Drive? Why yes, yes it was.

But not anymore. Now doctors were examining the color of his urine like a French sommelier ponders wine, judging color, density, consistency, even odor. It was awful getting old. The pain had been so bad recently, in fact, that hea great man!had even contemplated suicide, not once but twice. He had consulted priests on both occasions, and the spiritual ministers of his lifelong faith had helpfully advised him that his immortal soul wasnt worth the risk. The end would come soon, they said soothingly, it wouldnt be long.

When he awoke this particular morning in November 2007, creaky and tired as usual, the view from his rambling waterfront home on Wallachs Point, Connecticut, an hour north of New York City, had transformed from the inviting hues of summer to the foreboding greys of winter. The vast sea gurgling its winter froth seemed to reflect his grumbly mood.

Still, Buckley, the patron saint of modern American conservatism, an icon and a living legend, raised himself up and ambled over to the garage he had converted into an office more than forty years before. He took his seat at his oversized desk, pushed aside a huge number of books and articles and a few thousand shreds of paper, and began to write.

Partly thats just what he did. You dont write forty-odd books, thousands of newspaper columns, and boxes and boxes of letters by sipping coffee too long, pondering the sports page. Someone once told him that his accumulated papers fit into so many boxes at Yales Sterling Library that if you stacked them all on top of one another they would reach the top of the Washington Monument. To achieve that kind of productivity you get over your aches and pains, your sour moods, the greys outside, and you head to your desk to write.

In addition to habit, though, on this particular morning the old man with famously tousled reddish-grey hair also felt he had to work through something important. For that day, you see, he had just learned that yet another of his friends had passed away. This was not an uncommon occurrence for Buckley, then about to turn eighty-two. His sister Jane had died a few months earlier, and family departures were always hard, evoking memories of the family reserve. Meanwhile, his best friend of sixty years, Evan Van Galbraith, was in the midst of some thirty-plus radiation treatments, which would surely kill him shortly, too.

But these all paled in comparison to the passing of Patricia, his Ducky, his wife of fifty-seven years. That was devastating. Her departure nine months earlier had created a terrible void that Buckley felt deep inside his soul, as though the rug of life had been pulled out from under him, making him now and forevermore alone. What shall we do today? his son, Christopher, had asked shortly after her death. Well, replied the old man, with a sudden chill, I guess we can do anything we want to. The realization provoked a hollowness and a dread. Too much freedom was a terrible thing.

Pondering suicide had been unimaginable when Patsy was alive. But now that she was gone, well, things just seemed different.

And the departures kept coming. Today, staring at him from the newspaper on this cold November morning was the face of yet another. This one was different, though, different from the rest. Sure, it sparked the usual sadness of a friend departed, but it also initiated something else. In fact, what came whirling back to Buckley as he read through the obituary pages was the excitement of an entire era gone by, when ideas seemed to matter more, when a young and vibrant William F. Buckley, Jr., and the now departed Norman Mailer, smiling at him from the pages of the newspaper, were at the forefront of it all.

Mailer had once described theirs as a difficult friendship, and that was certainly true. There had been fights and struggles, battles and arguments. But despite their seemingly polar outlooks on Americaone left, one rightthe two men had been intimates during the 1960s and 1970s, when their ideas seemed to be vying for the soul of the nation. They had debated in huge venues; drunk together in intimate night spots; exchanged dozens of private letters; socialized together at the most memorable parties of the era; traded books, articles, and laughs, and, perhaps most vitally of all, had shared a deep love of America. They had dramatically different visions of what the country was and of what it could become. But they loved the promise and the dream. Their efforts to shape and improve America had made them key players in the revolution that was the 1960s.

Next page