All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

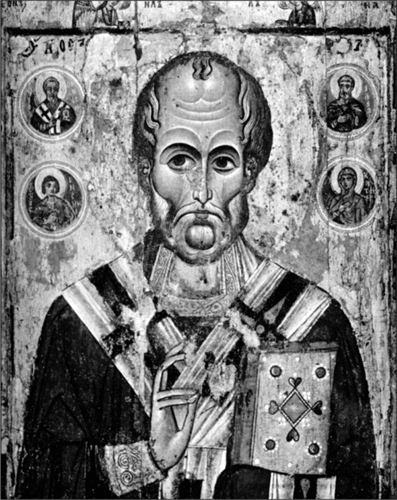

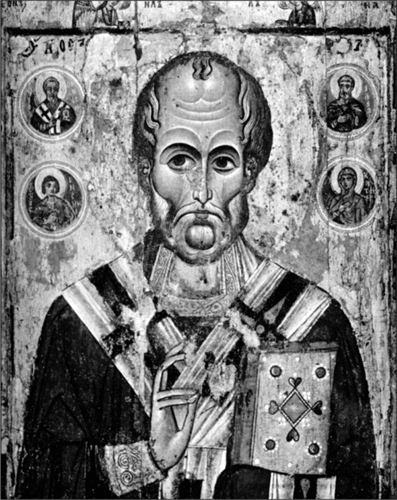

1. Santa Claus. 2. Nicholas, Saint, Bishop of Myra. I. Title.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

75 Sherbourne Street

Toronto, Ontario

M5A 2P9

www.mcclelland.com

ALSO BY GERRY BOWLER

The World Encyclopedia of Christmas (2000)

Contents

Introduction

C hristmas is the most important season of our existence. We spend at least one month out of each year of our lives under the spell of the planets most widely celebrated holiday. At no other time are our feelings as intense; at no other time are we so caught up in a relentless round of preparation, enjoyment, and recovery. We plan, we drive, we shop, we buy thus making merry the hearts of jewellers, booksellers, and purveyors of toys, perfumes, and motorized tie racks. We wrap, we conceal, we wait. We clean and decorate; we bake, cook, brew, and ice; we fast, worship, pray, and celebrate. We visit, we host; we tell stories to our children (sometimes true ones) and listen to the wishes (always sincere) they tell us. We write cards, address envelopes, and lick stamps. We renew our acquaintance with holly, pine boughs, gingerbread, marzipan, and tinsel. We seek out, transport, and erect in our homes dead trees, which we then ornament with baubles that hold meaning only for that month. We sing songs, some of great spiritual power, some of consummate silliness at what other time of the year is our speech of reindeer, angels, elves, chestnuts, and kings? We joyfully open gifts in the presence of loved ones and think sadly of those who are absent. We eat, drink, and are bloated. Too much is our catch phrase we are too generous, too gluttonous, too sentimental, and too tired. We vow that next year will be different, forgetting that excess lies at the heart of celebration.

If, for reasons of religion or irreligion, we choose not to participate directly in the Christmas phenomenon, we discover that its reach is everywhere. There is no way to avoid the holiday music on the radio or in the malls; we are assailed by hearty greetings, beset by long lineups, and daunted by the hunt for a vacant parking spot. If we are repelled by the consumerism of our neighbours or made melancholy by their happiness, we dare not voice our unease, lest we be called Grinch, or worse. Christmas is inescapable.

Two deities preside over the season. One is the baby Jesus, the divine infant, God incarnate to all Christians, adored by shepherds and angelic hosts, celebrated in carols, stained glass, and midnight masses. Numberless are the books, films, and works of art dedicated to exploring his significance. Christmas marks his birth two thousand years ago in a Middle Eastern stable.

The other is Santa Claus, the dominant fictional character in our world. Neither Mickey Mouse nor Sherlock Holmes, Ronald McDonald nor Harry Potter wields a fraction of the influence that Santa does. He is a fundamental part of the industrialized economy; he is a spur to consumption but also to charitable giving. He provides employment for millions, encourages good behaviour in the young, and unifies families and nations in seasonal rituals. He is celebrated in story, song, movies, lawn displays, and malls. His image is recognized and loved all around the planet.

All of Santas prestige derives from his role as the chief gift-bringer during the celebration of Christmas. Though Christmas is an ancient festival and one with which gifts have been associated from the very beginning, Santa Claus himself is a rather more recent arrival. Where did he come from? Is he a figure of mythology, a creation of literature, a tool of clever capitalists? How did he come to hold sway over such a large part of our existence? An account of his life will tell us much about the power of memory and magic, the duties of childhood and parenting, the clash of the commercial and the sacred.

I

His Long Gestation and Obscure Birth

O ne evening in Bethlehem, in the twenty-sixth year of the reign of Caesar Augustus, a party of astrologer-magicians knocked on the door of a house where a young family from Nazareth was staying. Ushered into the presence of the new mother and her child, these foreign visitors, whom legend would number as three and name Gaspar, Melchior, and Balthasar, unwrapped their bundles and presented the baby with gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Thus were the very first Christmas presents delivered.

Strangely, centuries would pass before the connection between the celebration of the nativity of Jesus and gifts became widespread. Early Christians thought that marking the birthday of their Lord was not unlike the way pagans honoured their rulers. The Alexandrian theologian Origen in the third century spoke out against observing the anniversary of Christs birth as if he were some sort of King Pharaoh. Believers tried to live inconspicuously among their neighbours in the Roman Empire and walked a fine line between harmless cultural accommodation and taking part in forbidden heathen ceremonies. Since most festivals of the time had strong religious components, it is not surprising that Christian leaders had serious misgivings about how their flock celebrated the holidays, particularly those extravagant festivities that marked the end of the year.

The Roman world began their festivals in late December with Saturnalia, which during the five days starting on December 17 honoured Saturn, an ancient agricultural deity. All work, except the preparation of food, was forbidden, and the world, for a short time, was turned upside down. Slaves and masters temporarily reversed roles, and a Lord of Misrule was elected to oversee this brief return to an older Golden Age. It was a time of obligatory merriment, banqueting, gambling, suspension of quarrels, cross-dressing, and masquerades. Houses were decorated with candles and greenery, and small presents were exchanged between friends; children were given little dolls (perhaps as a token of the time when human sacrifices were made to ensure fertility of the crop). Next came the winter solstice, Brumalia, and after its introduction in A.D . 286, the Feast of the Unconquered Sun a day meant to inspire patriotism and good thoughts about the emperor, and this led to the Kalends of January, which marked the beginning of the New Year.