Published in 2019 by New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2019 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2019 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Alex Ward: Editorial Director, Book Development Brenda Hutchings: Senior Photo Editor/Art Buyer Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Rosen Publishing

Greg Tucker: Creative Director Brian Garvey: Art Director Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Crime / edited by the New York Times editorial staff. Description: New York : New York Times Educational Publishing, 2019. | Series: Changing perspectives | Includes glossary and index. Identifiers: ISBN 9781642820133 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642820126 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642820119 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: CrimeJuvenile literature. | Criminal investigationJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC HV6789.C756 2019 | DDC 364.152'3dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

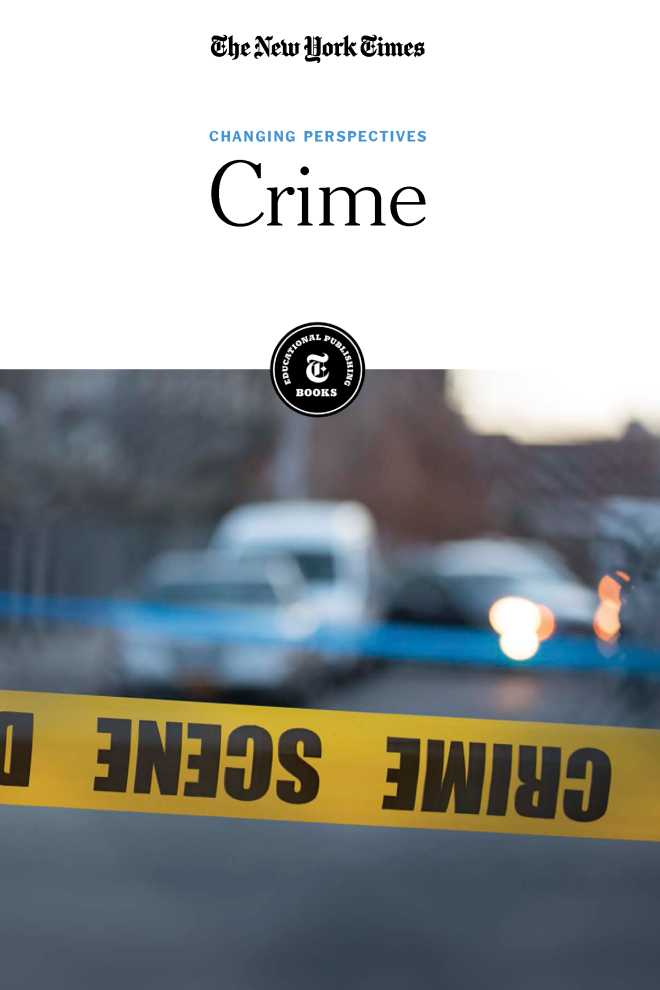

On the cover: The NYPD investigates the crime scene in 2016 where a man was shot and killed in the Bronx; Edwin J. Torres for The New York Times.

Contents

CHAPTER 1

The Late 19th Century

CHAPTER 2

The Early 20th Century

CHAPTER 3

The Mid-20th Century

CHAPTER 4

The 1980s and 1990s

CHAPTER 5

The 2000s and Beyond

Introduction

IS THAT A CRIME? Well, it depends. Crime is a social construct it means what people agree it means. What constitutes a crime changes over time. And it can change depending on who is in power. Certain acts, such as rape, murder, assault and larceny, are universally thought to be criminal. But what about slavery, the exploitation of workers, extortion and prostitution? When The New York Times began reporting in 1851, these activities were not illegal. In fact, the first police forces were established in part to protect the interests of the people engaged in running such businesses. Police officers were paid to capture escaped slaves, suppress worker strikes, extract payment from small business owners for protection from powerful gangs and ensure that those who frequented the red-light districts paid for services rendered. In short, the police were there to protect the wealthy, educated upper classes from the dangerous poor, immigrants and racial minorities. Although the role of the police force has changed over time, this history has determined the ways in which we think about crime and criminals today.

Ideas about crime and criminal behavior changed significantly throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century. One way to follow these changes is to look at the criminalization of the drug cocaine. In the late 1800s, cocaine was hailed by doctors and druggists as a miraculous cure for common colds and toothaches. Immensely popular, it was added to beverages, cigarettes and beauty treatments. However, when it became clear that the drug was more harmful than helpful, heavy restrictions were placed on its manufacture and distribution. In the 1960s, cocaine re-emerged as big business on the black market. And in the 1980s, use of its high-addictive concentrated form, crack, had become widespread in urban black communities. Addiction-fueled property crime and gun-related homicide rates jumped. President Richard Nixon declared a war on addiction in 1972, and drug-related arrests became common. Prison populations exploded, and a disproportionately high number of black men were incarcerated.

RAMIN RAHIMIAN FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

As another drivers car is towed away in the background, a man is detained for avoiding a San Jose Police Department Sobriety and Drivers License Checkpoint in San Jose, Calif.

This is just one example of the ways in which ideas about what is criminal have evolved. This book looks at several, including organized crime, white-collar crime, sex crimes and politically-based crimes. Some acts that were legal in the mid-19th century, such as enslavement, prostitution and selling cocaine, are criminal today. And some acts that were illegal during the early 20th century such as selling alcohol and public homosexual behavior are now legal. Crime changes to suit the times.

Chapter 1

The Late 19 th Century

The first municipal police forces were established in the 1830s. Their jobs were to capture and return escaped slaves and maintain order among the people. Sometimes this meant apprehending murderers or grand larcenists, but often it meant arresting the homeless poor, the desperately hungry and the uneducated laborers drunk on alcohol sold by the barrel. Corrupt police officers were ruled by businessmen and politicians, and crime was defined as any act that ran counter to the interests of the ruling class.

Law Courts: Court of General Sessions

BY THE NEW YORK TIMES | OCT. 13, 1853

BEFORE RECORDER TILLOUS The case of Patrick Darcy, whose trial on an indictment for manslaughter has for some days been dragging its slow length along, has terminated in a verdict of not guilty.

COUNTERFEIT MONEY.

John Meehan was placed at the bar on an indictment charging him with passing a counterfeit Bank note for five dollars, purporting to be of the Fall River Bank of the State of Massachusetts. The District Attorney in summing up the case, told the Jury that at this moment the amount of counterfeit money in this country was absolutely equal to half the genuine notes in circulation. The Jury having found the prisoner guilty, with a recommendation to mercy on account of his previous good character, he was sentenced to five years imprisonment.

JUVENILE CRIME.

James Hepan, a youth found guilty of stealing nine pieces of silk handkerchiefs, worth $38, the property of James S. Davies, was sent to the House of Refuge.

IMPRUDENT ROBBERY.

Thomas J. Muhony was indicted for stealing a horse and wagon, the property of Benjamin C. Leveridge. It appeared that the complainant, who is a physician residing at No. 149 East Broadway, drove, in the course of his profession, to No. 98 Chatham Street, and went in, leaving the property outside the door. On returning outside again he missed it, and it was soon afterwards found in the possession of the prisoner, at Third Avenue, near Forty-second Street. The accused could only account for his having the property in his possession by saying that he was very drunk and really did not know. The Jury, after some deliberation, found him not guilty.

GRAND LARCENY.

Sophia Hutchinson was found guilty upon an indictment charging her with stealing a gold watch, and sentenced to three years imprisonment.

THE HORNS OF A DILEMMA.

Francis Gallagher was placed at the bar on an indictment charging him with stealing a cow belonging to James Whalon. It appeared that the animal in question was kept in a yard, the security of whose enclosure was anything but satisfactorily established, and in some way or another found its way out thereof. The prisoner was seen by an officer leading it by the horns in Fourth Avenue, and on being questioned, was, as the police functionary said, very scarey. He, however, subsequently stated that he found the animal, and was trying to take her home. He was, moreover, inebriated at the time. The Jury was placed on the horns of a dilemma as to whether he intended to commit a felony or not, but after retiring to deliberate, found the prisoner not guilty.