Epilogue:

The Late Interiors

[S]he is, in spite of herself, weighing the value of the wordthe value of the gifts. Little by little she stows them tranquilly away. But there are so many of them that in time she is forced, as her treasure increases, to stand back a little from it, like a painter from his work. She stands back, and returns, and stands back again, pushing some scandalous detail into place, bringing into the light of day a memory drowned in shadow.

Colette, Break of Day

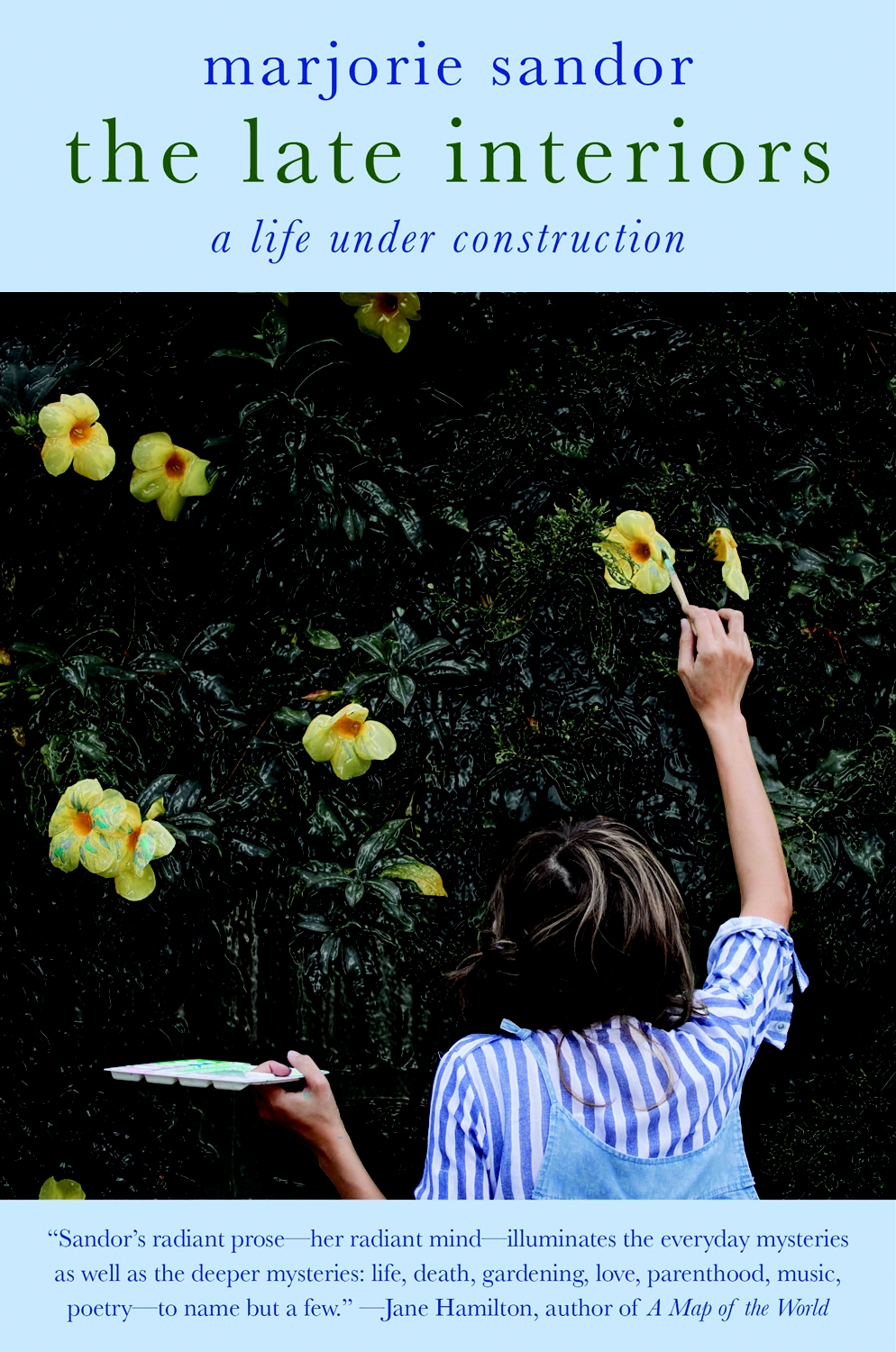

C onsciousness , Bonnard scribbled in his daybook, the shock of feeling and memory. In his late still lifes and interiors, he chose to stay close to the objects of his studies, to dab at the canvas a little at a time, walk away and come back, so he wouldnt stray too far from the original impulse, that ephemeral thing always slipping away. Its been said of him that he didnt so much paint what he saw as paint what he remembered. So it is that gradually, over the long process of composition, his domestic scenes begin to shape an image, not of some recognizable place, but of the memories contained in their colors, their shapes. We see, at the edge of the frame, or feel the absence of, the wife who once poured tea from the teapot, or lifted the lid of the blue butter dish. So in the vibrant presence of the breakfast table, there is absence, too. The grief already dwelling in us, and the grief we know is coming our way. For it will come. In what form we cant know.There is, finally, no way to prepare for it.

In his later years, after his wifes death, Bonnard turned more and more to the self-portrait, as if preparing the canvas for his own absence. Even when he paints his own shadowy self, bald and bespectacled and bare-chested, seated before the bathroom mirror, he is ever the withdrawn observer, the recording angel. As before, its the little domestic objects on the shelf that hover and speak: the shaving brush, the bar of soap, the glass bottle gone faintly gold. These are the eloquent objects, heightened by the shadowy, naked human figure who watches them, quietly amazed.

What lies ahead? What treasuring up and what loss, and how will we endure it? How can we prolong the evening light flooding in through the dogwood?

The dogwood, which, to be honest, began to suffer blight in the ten years since I began my garden journal. Men come in a truck three times a year to spray it now. It is healthy again, but always desperately leaning away from the blue spruce, trying to get enough light. We trim back the spruce, but its vigor is astonishing.

Not long ago,Tracy bought me two copper cowbells to hang in our backyard. It took me a while to figure out where to put them. In the logical spota thick, low-hanging branch of the blue sprucethey were too well protected from the wind and rarely touched each other, and when they did, rang only faintly. One day I moved them onto a fragile, exposed branch of the delicate dogwood. And only thenvulnerable, unsheltereddid they make their music.

To wait, to wait, wrote Colette, striving to learn how to fight the impulse to go after life, after love, to feed her sensual hungers as they arose. In her early fifties, the age I am now, she held her favorite fountain pen in her hand, the one with the softened gold nib, and did not write. Then she wrote, later, of not writing. In this way she learned, after a fashion, to wait, though this was not her natural inclination.

There are other forms of waiting to learn.We waited several years for a seed to germinate, take hold, in my womb. It didnt happen: like my mother in her late forties, I had two fibroids clinging to the uterine wall, blighting the growing place, and a hysterectomy was recommended. Still, in the midst of that disappointment, such joy at watching Hannah thrive and grow into a young woman.

We live with the doctors words to Tracy after the heart surgery: his warning that the transplanted bypass vein eventually wears out, usually after ten years. Youll let us know, wont you? Not a day goes by that Tracys chest muscles dont twitch or twang, a physical reminder of what hes been through, of what might lie ahead. Not a day goes by that I dont find myself registering the specific depth of his blue-green eyes, the color that blooms beneath his cheekbones. I remember how he once stood at our back kitchen window, holding out his arms, then bringing them in close to his body, as if to capture the last of the afternoon light.

Such thoughts propel me, on a midsummer day, out into the back garden, out to pull up the tenacious weeds starting up between the beds. The shepherds purse and dandelions, the bunchgrass and oxalis. The ones whose names Ive yet to learn.

These days, its the act of prying away at the roots of the intransigent dandelions that calms me. Returns me to the present.

Listening helps too, and in this regard, the cowbells have been a great gift. Theyre the first music I can hear from this kneeling position: just behind me and over my head, they lightly knock into each other and produce a quiet lowing. Above them the dogwood rustles, and past that, the trees of the Newman Commons courtyardthe old elm and fir and that young aspenrattle and whisper. The elm looks a bit fragile this yearfewer leaves, it seems to me. But the canopy is more or less intact, and sometimes theres singing in the new chapel back there, or the sound of an afternoon barbecue in front of the new apartment building. Hillside is intact, with all its mullioned windows, as are two other of Margaret Snells cottages. Painted pale green now, with white trim. Students live in one of them, and in the other are two seminarians and a priest, all from Argentina.

From farther out comes the slick swoosh of traffic on Monroe Street and campus, itself composed of many layers, the grinding of trucks bringing deliveries to Chemistry, the softer roar of cars, bicycles, skateboards, a blur of sandpaper and thunder.Voices human and animal, and at night, still, the pleasure cries of the young emerging from the pubs and cafs.We could swear theyve gotten wilder in the past ten years. But it could just be that were getting older. Soon well be white-haired professors with our earplugs firmly lodged.