To my mother and father, Anita and David Abrams, in their ninety-second and ninety-third year

Contents

This Must Be ProgressThe Master of Modernism on God, Graphics, and Other

Devotions

Foreword

Deyan Sudjic

Janet Abrams began her career as a critic at what, in retrospect, seems a very particular moment in the 1980s, a time when there seemed to be a major shift in attitudes toward architecture and design. The first whispers of a reaction against an ascendant post-modernism were already in the air, sometimes with paradoxical results. Feeling insecure, SOM put itself on the couchand on the lookout for alternatives to corporate modernism. At the first Venice Architecture Biennale, held in 1980, postmodernisms defining moment, the Strada Novissimaan installation of twenty facades by twenty architectsput Rem Koolhaas on show alongside Michael Graves. Everything was in play, and future directions were still to be defined. Meanings and context seemed as important as plans, appearances, and techniques.

The upstart London monthly Blueprint, founded in 1983 by a group of journalists, photographers, writers, and designersof which Janet was one and I was anothervigorously attempted to play its own skeptical, Anglo-Saxon part in this process. The magazine set out to be both iconoclastic and disposable, while aiming to root architecture, design, graphics, fashion, and their visual representation in the popular culture of the time. We thought we were going to turn design and architecture upside down. As is usually the case, this took the form of doing all that we could to champion a new group of names, drawn from among our contemporaries. As they rose, so would we. (Now that print has lost much of its authority, we wait with more or less resignation for another generation to dispatch us, in electronic haiku, 140 characters at a time.)

Fashion cycles are the natural means for edging out one generation to make room for another, but they dont always make for the most reliable of critical judgments. Janet, however, has never been interested in adopting fashionable attitudes. What drives her is the exploration of ideas, and that is what makes her writing compelling reading today. She combines endless curiosity and erudition with a fascination for observation and detail across the broadest cultural spectrum, in a way that might reflect an early interest in the work of the trenchant English critic Reyner Banham, who, like Janet, combined a sharp wit with a determination to extract every scrap of meaning from the smallest of details. Banham, too, made the decision to move to the United States, but his influence was still pervasive at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London when Janet arrived there as an undergraduate student immediately after his departure.

The breadth of her writing shows her ability to engage with some of the most formidable voices of our time, dealing with Peter Eisenmans bicoastal psychoanalysis and Koolhaass first significant completed buildings on her own terms. She has found herself in Los Angeles, talking to Disneys Michael Eisner, and in a casino designed by David Rockwell, exploring the nature of mapping, play, and craft. Writing, for Janet, is a voyagea mission to understand, to explain, and sometimes to hold to account. She has the ability to frame complexity in pursuit of clarity.

Janets perspective over the years has grown beyond architecture to encompass the wider horizons of design, technology, and their meaning for the world. It follows her professional trajectory, from journalism in London to a doctorate at Princeton University to directorship of the University of Minnesota Design Institute, and then on to an MFA at Cranbrook Academy of Art with interludes at the Netherlands Design Institute in Amsterdam and the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal. Its a list of institutions and actions like no other, one that reads like a timeline of most of the key developments in design culture over the past four decades. Her writing also reflects the impact of the digital explosion, and the subsequent renewal of interest in the physical and the mark of handwork. That interplay between thinking and doing is what makes her uniquely qualified to explore the nature of the material world against the background of accelerating change.

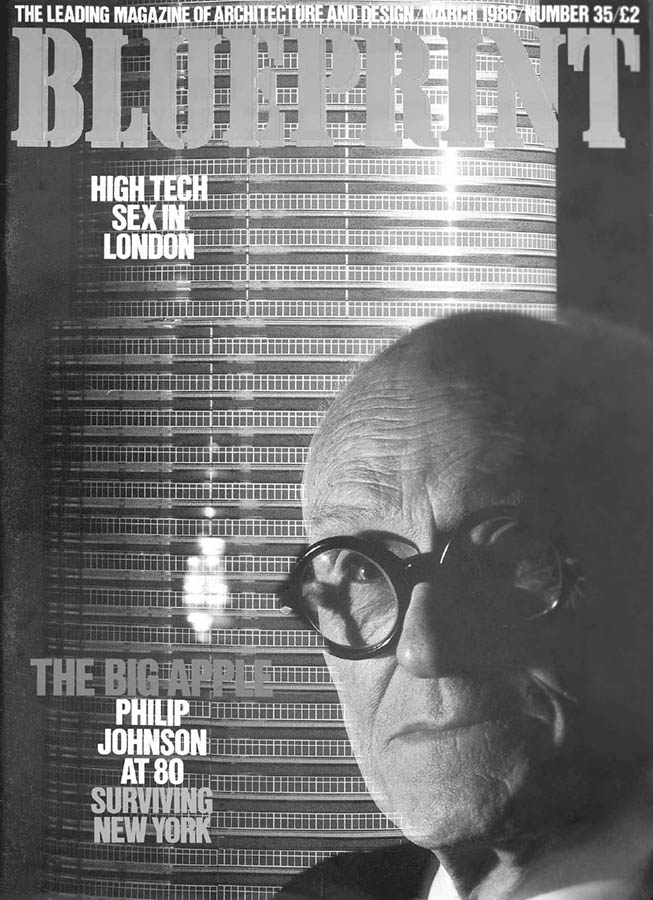

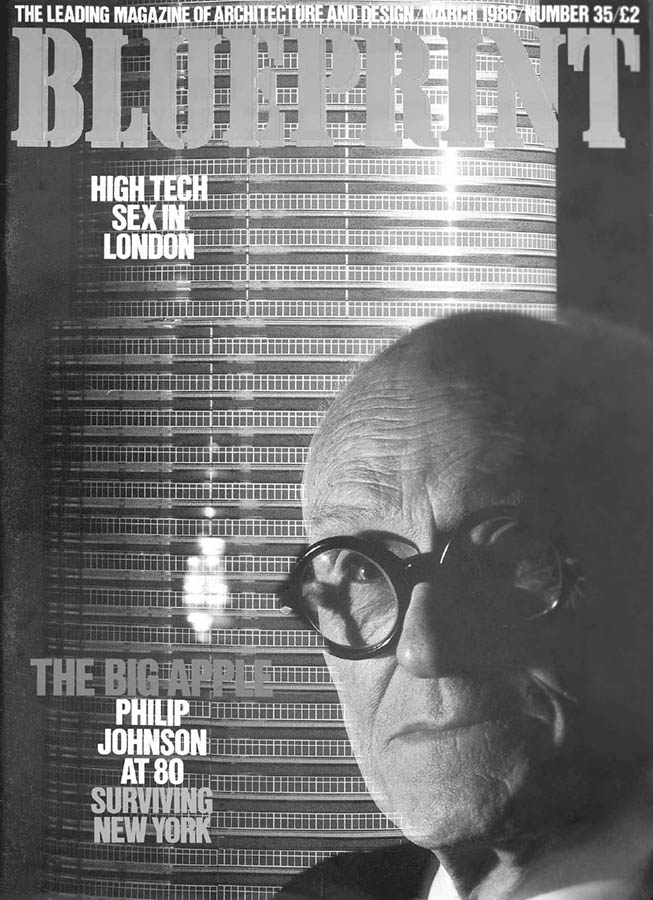

Blueprint, March 1987 (despite the error in the date on the cover): Philip Johnson, photographed by Phil Sayer, for a special issue on New York

Introduction

Tightrope Walking with the Circus of the Perpetually Jet-Lagged

Janet Abrams

Have you ever wandered down a street in a familiar city, noticed a new building asserting itself in strident aesthetic contrast to the surrounding urban fabric, and asked yourself: What were they thinking? Or navigated a cumbersome website and wondered: Isnt there a simpler way?

These are the kinds of questions that drove me from the 1980s to the 2000s, as a critic on architecture, design, and digital media. Early in my journalism career, I gravitated toward the interview as a mode of inquiry; the extended profile soon became my preferred format. I wanted to get beyond press release platitudes, to dig into the ideas, theories, and even emotions underlying the work of contemporary architects and designers. Their creative choiceswrit large as buildings, interiors, urban spaces, mass-produced objects, everyday information design, and commercial softwareplay a profound role in shaping our lives then, as now, even if the dominant aesthetics today are quite different from decades past.

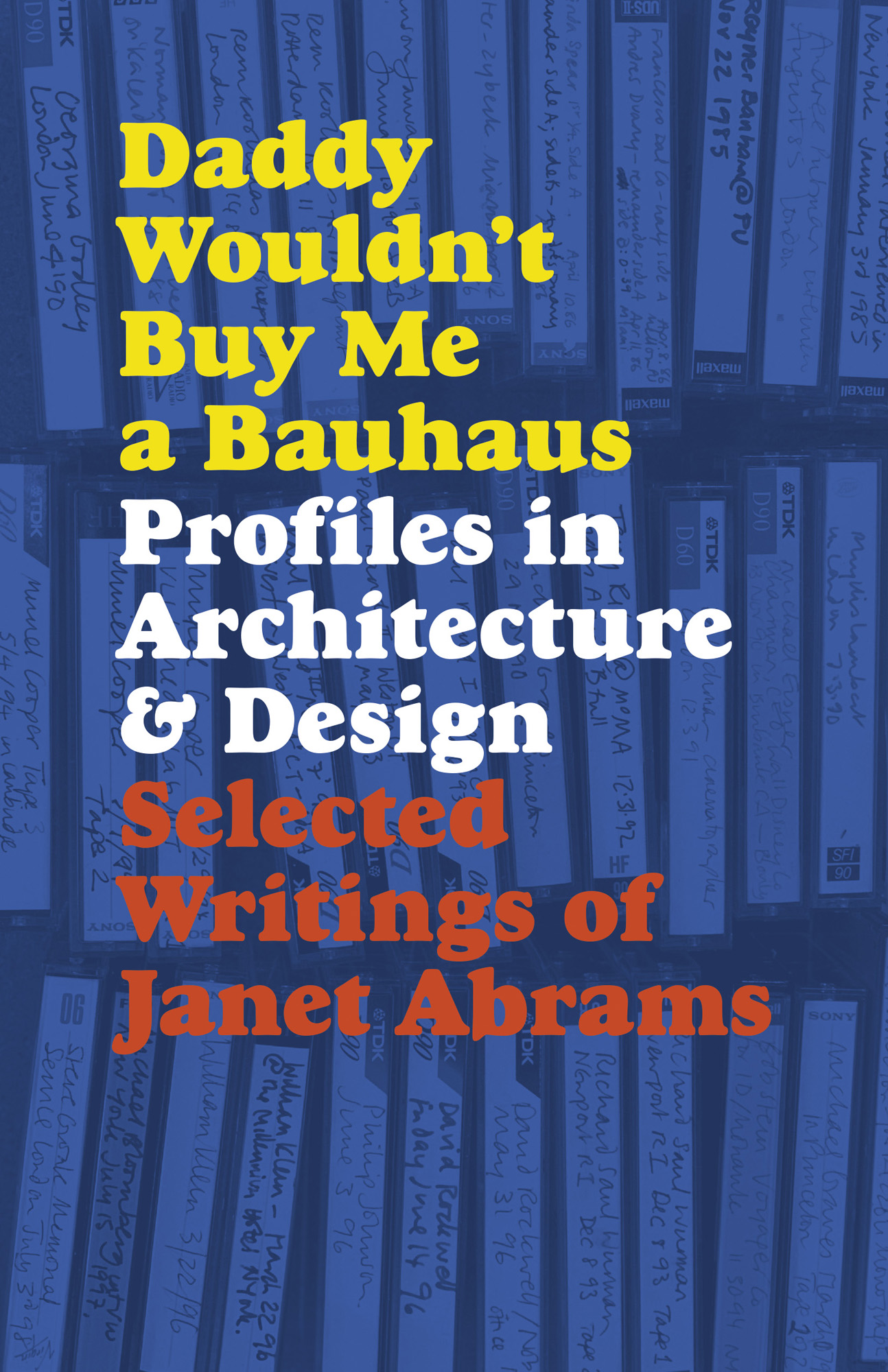

Daddy Wouldnt Buy Me a Bauhaus gathers twenty-six profiles, the majority of which originally appeared in two design magazines:

Collectively, they form a portrait of an era: the cusp between analog and digital, in which the solid objects of architecture and design were beginning to face significant competition from the distributed virtual experiences of the Internet and other new media platforms.

It was also the era in which certain architects began to garner international celebrity. During the 1980s and 1990s, the expansion of networked electronic communications and adoption of computer-aided design made it easier to design buildings in one time zone and construct them in another, transforming architectural practice into a multinational enterprise. Architects based in the United States and Europe became increasingly sought-after by clients around the globe, who, thanks to a bevy of international architecture magazines, clamored for buildings that would become cover stories (or today, ready fodder for Instagram). Suddenly, signature styles were an export commodity modified somewhat to acknowledge the specifics of site and local culture. Hence Rem Koolhaass wry expression, which I have borrowed from our conversation (pages 97108) for the title of this essay.

My role as critic and outside observer, especially as US correspondent for Blueprint in the 1980s, enabled me to select individuals for interview whose work and opinions were not yet widely known, particularly on the other side of the Atlantic. (It should be noted that few of them worked alone; if their practices then consisted of just a handful of people, today they may employ dozens, even hundreds, in multiple offices around the world.) Some were already renowned veterans of their discipline at the time of my interview (architects Berthold Lubetkin and Philip Johnson; graphic designer Paul Rand); others were on the cusp of international fame (architects Frank Gehry and Rem Koolhaas). Information designers such as Muriel Cooper and Ben Fry were barely known beyond a tight circle of fellow specialists, but would come to be recognized as pioneers who laid the intellectual and aesthetic groundwork for the digitally mediated culture we now inhabit.

Next page