Klees Birthday Party

I t was the fall of 1972, and I was driving Anni Albers down the Wilbur Cross Parkway from my familys printing company in Hartford, Connecticut, back to her and Josefs house in the New Haven suburb of Orange. The Albersesshe was seventy-four, he eighty-fivewere the last two surviving members of the Bauhaus faculty. I had been introduced to them two years earlier, and was now working with Anni on a limited edition print in which she was making ingenious use of photo-offset technique that was generally applied to commercial lithography rather than abstract art.

Anni and I were in my two-seater hatchback car, an MGB-GT which the Alberses praised as an exemplar of the Bauhaus ideals of impeccable functioning and no wasted space. We prefer good machinery to bad art, Josef had explained. But the torrential rain that afternoon was so intense that Anni was an anxious passenger. Please pull over under that bridge until the downpour gets lighter, she requested in her German-accented English, the controlled politeness barely masking an inner desperation. In Mexico, when we would go there in the thirties with friends in their Model A, we often had to pull over during storms, she added, to make it clear that she was not criticizing my driving.

The cascade of rain on the windshield was intensifying and the visibility was becoming dire as I stopped the car. Under one of the charming carved stone parkway bridges built by the WPA, Anni momentarily closed her eyes in relief. She was an adventurerluring Josef from the Dessau Bauhaus to Tenerife for five weeks on a banana boat in the 1920s, getting them to Machu Picchu in the fiftiesbut she also was chronically anxious, which she directly attributed to the period in 1939 when she had to get her extended family out of Nazi Germany; her parents ship docked in Veracruz, in Mexico, where she and Josef had to scramble to bribe one person after another before Annis increasingly desperate mother and father finally managed to disembark. At twenty-four, I was soaking up Annis life experiences as if they had been my own, and was enchanted by the consuming dedication she and Josef had to the making of art and by the way their work enabled them to withstand anything. Now, in the sports car under the bridge, the woman who had become director of the Bauhaus weaving workshop assured me that our journey had been worth its challenges because of her thrill at supervising the presswork of her latest prints, and the importance of her being there to oversee the mechanical adjustments that intensified the tonality of the gray ink.

Josef Albers, photo of Anni Albers. Anni disparaged her own looks; others considered her a great beauty. This is one of the many pictures Josef took of her over the years.

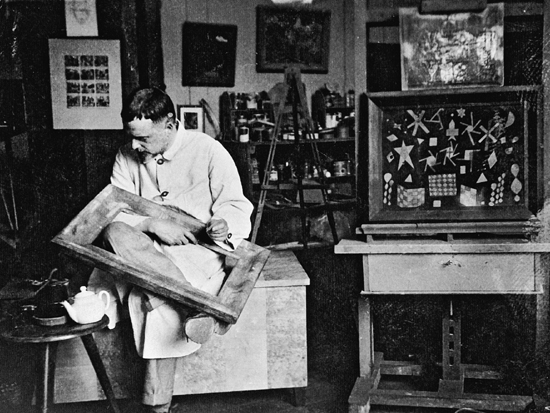

I had switched the motor off. Anni turned to me and said with a smile, You deserve a reward. I know you have been wanting to hear about Paul Klee for a long time. Since our first meeting, I had badgered her with questions when either she or Josef mentioned Klee, Kandinsky, or their other colleagues. Both the Alberses, however, were so focused on their current work and uninclined to nostalgia that I had not been able to elicit more than a few cursory remarks. I will tell you something I have never told anyone beforeabout his fiftieth birthday. It was 1929. Klee, Anni told me, was her god at the time; he was also her next-door neighbor in the row of five superb new masters houses in the woods a short walk from the Dessau Bauhaus. Although the Swiss painter was, in her eyes, aloof and unapproachablelike Saint Christopher carrying the weight of the world on his shouldersshe admired him tremendously. She had even acquired one of his watercolors after being bowled over by an exhibition in which Klee tacked up his most recent work in a corridor of the Bauhaus when it was still in Weimar. The purchase had been a rare public admission of her familys wealth, which she normally concealed: she told me that she had been so embarrassed by the appearance in Weimar of two of her uncles in a Hispano-Suiza that she had begged them to drive off immediately. But though her ability to buy the painting conspicuously set her apart from the other students in difficult economic times, she still could not resist acquiring Klees composition of arrows and abstract forms. Now, as her god approached his major birthday, Anni heard that three other students in the weaving workshop were hiring a small plane from the Junkers aircraft plant, not far away, so that they could have this mystical, otherworldly mans birthday presents descend to him from above. He was, they had decided, beyond having gifts arrive on the earthly level where ordinary mortals live.

Klees presents were to come down in a large package shaped like an angel. Anni fashioned its curled hair out of tiny, shimmering brass shavings. Other Bauhauslers made the gifts the angel would carry: a print from Lyonel Feininger, a lamp from Marianne Brandt, some small objects from the wood workshop.

Anni was not originally scheduled to be in the four-seater Junkers aircraft from which the angel would descend, but when she arrived at the airfield with her three friends, the pilot deemed her so light that he invited her to get on board. For all of them, it was their first flight. As the cold December air penetrated her coat and the pilot fooled with the young weavers by doing 360-degree turnabouts as they huddled together in the open cockpit, Anni became suddenly aware of new visual dimensions. She told me she had been living on one optical plane in her textiles and abstract gouaches. Now she was seeing from a very different vantage point, with the factor of time added in. She was too fascinated to be afraid.

She guided the pilot by identifying the house the Klees shared with the Kandinskys next door to her and Josef. Then he swooped the plane down and they released the gift. The angels parachute didnt open fully, and it landed with a bit of a crash, but Klee was pleased nonetheless. He would memorialize the unusual presents and their delivery in a painting that shows a cornucopia of gifts on the ground in good condition, even if the angel looks a bit the worse for wear (see color plate I). James Thrall Soby, who owned the colorful canvas, told my wife and me that he thought it depicted a woman passed out drunk at a cocktail party, with the golden brushwork Klee used for Annis brass shavings representing the socialites blond hair, but Annis account revealed the actual facts.