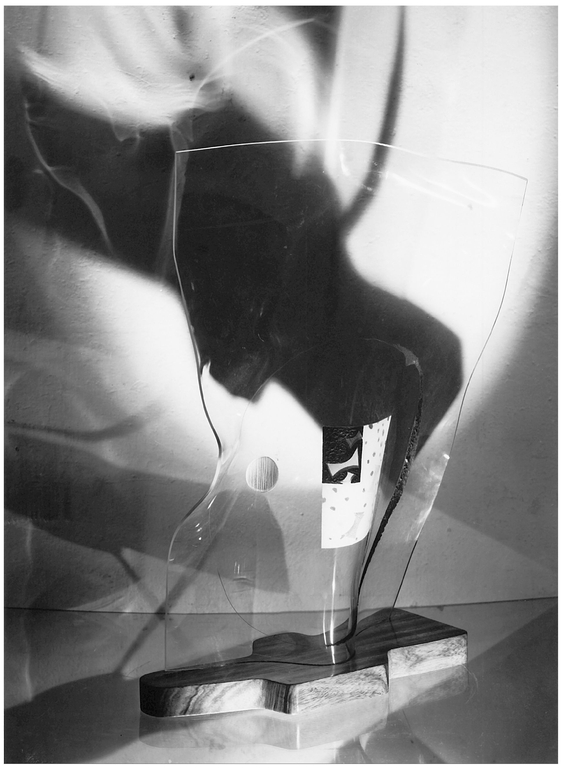

Abstract of an Artist:

L. Moholy-Nagy.

Space modulator with highlights

(Plastic shaped by hand, 1942.)

The ordinary person is bewildered by contemporary art. The teaching of a distorted history of art, rooted in dogmatic definitions of what ought to constitute art, often prevents him from approaching new modes of expression. Anything which he finds difficult to understand makes him impatient and angry, sometimes even hostile. But there are ways of meeting the situation. The observers emotional and intellectual interest can be stimulated so that he approaches the subject with a more positive attitude. He can be shown that without special preparation only a minority can follow new trendsmainly because the professional artist, through daily work with his material, acquires a superior understanding of his means, and is led to newer and newer formulations that supersede old standards. These findings are the result of an organic process, a growth in knowledge, experience, and intuition. This can hardly be matched by the layman. But the new formal solutions can act as catalysts for the few who, because of an inclination similar to that of the artist, react positively. Then, slowly and almost unnoticed, as if by a process of osmosis, the work of the new artist diffuses and penetrates through every phase of life. In from thirty to fifty years the process reaches a saturation point. The new form of expression has become part of civilization and the cycle will be renewed.

The process of diffusion may be accelerated. Intellectual preparation and criticism may undo dogmas. Though it is doubtful whether art can ever be fully explained, it may be helpful to the reader to retrace my own development, and to show how my work in abstract art grew out of a gradual grasp of means and interrelations.

Seeming chaos. I did not begin as an abstract painter. Intimidated by the apparent chaos of contemporary painting, then represented by the fauves, cubists, expressionists, and futurists, I turned to solid values, to the renaissance painters. I had no difficulty in understanding them. Was I not prepared by novelists and biographers to appreciate their monumentality? Raphaels worldly madonnas, the heavenly smile of the Gioconda and her fine hands, the weighty dignity of Michelangelothese were already interpreted by writers. We ordinarily like things which we understand, and we usually look for those things which we know by heart. They afford an agreeable reassurance, and confirm our education. It did not occur to me that beyond the illustration of a mythological and religious story, pictures must have other qualities. My eyes were not yet trained to see. My approach was more that of hearing the pictures literary significance than of seeing form and visual elements. I was conscious neither of these fundamentals nor of the technique of execution. I would not have

been able to distinguish between originals, copies, or fakes. Then came my discovery of Rembrandt, especially of his drawings. They seemed to be carried only by emotional force, radiating psychological depth and introverted suffering. Impressed by the startling discoveries of psychoanalysis, I found in Rembrandt a foreshadowing of a technique demonstrating this kind of knowledge. In addition, not having much experience in draftsmanship, but haunted by a desire for quick results, my own drawings seemed to have an affinity with Rembrandts nervous sketches. The next step was Vincent van Gogh. Again, I was more attracted to his drawings than to his paintings. The analytical nature of his ink drawings and their peculiar texture taught me that line drawings ought not to be mixed with half tones; that one should try to express three-dimensional plastic quality by the unadulterated means of line; that the quality of a picture is not so much defined by the illusionistic rendering of nature as by the faithful use of the medium in new visual relations. (Since then I have learned that the artist may mix techniques; in fact, he can do whatever he pleases, providing he masters his means, and has something to express.)

The young painter passes beyond dilettantism, mere subconscious doodling and somnambulistic repetition of examples when he begins to discover problems for himself and then tries to solve them. To consciously work out such problems does not constitute a danger, either of losing the potentiality for future development, or emotional freshness. Anyway, the complexity of an expression is usually beyond conscious grasp. The conscious part is a small component, which helps to synthesize the elements, apart from the act of intuitive coordination. Through my problem of expressing everything only with lines I underwent an exciting experience, especially as I overemphasized the lines. In trying to express three-dimensionality, I used auxiliary lines in places where ordinarily no lines are used. The result was a complicated network of a peculiar spatial quality, applicable to new problems. For example, I could express with such a network the spherical roundness of the sky, like the inside of a ball. In the same way, I could render a nude with all the complicated compound curvatures of the body which the traditionally subtly flowing shadows, translated into half-tones, had had to define as organic plastic form. Suddenly I saw that this experiment with lines brought an emotional quality into the drawings which was entirely unintentional and unexpected, and of which I had not been aware before. I tried to analyze bodies, faces, landscapes with my lines, but the results slipped out of my hand, went beyond the analytical intention. The drawings became a rhythmically articulated network of lines, showing not so much objects as my excitement about them.

This again cut a path into the jungle. I learned that the manner in which lines are related, not objects as such, carry the richer message. Van Gogh appeared in a new light. I grasped much better the meaning of his curves and shapes. That I had a minor, but entirely personal problem in my work, taught me to recognize and even to look for other painters problems. Edvard Munch, the Norwegian painter, Lojos Tihanyi, a Hungarian, Oscar Kokoschka, Egon Schiele, Franz Marcall these appeared decipherable to meor at least so I thought. I was very much affected by the discovery that, for them, nature was only a point of departure, and that the real importance

Arrangement for a Bauhaus festival, 1926.