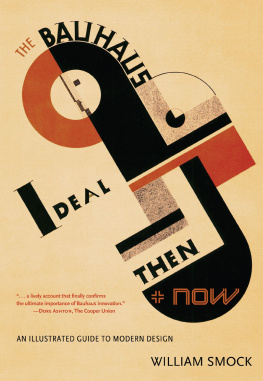

Published in 2004 by

Academy Chicago Publishers

363 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60654

First paperback edition 2009

Copyright 2004 by William Smock

Printed and bound in the U.S.A.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

All illustrations are by William Smock with the following exceptions:

: Catalogue page from Isamu Noguchi Rosanjin Kitaoji, Osaka, Yomiuri Shimbun, 1996, page 169. Photos by Kevin Noble courtesy of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation. Used by permission.

: Graphic design example 2003 Grace Sullivan. Used by permission

: Symbols from Schiphol Airport, Amsterdam

: Olympic sports palace, Rome, 1960. Figure 131 from Aesthetics and Technology in Building by Pier Luigi Nervi, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1965. Used by permission.

: Chart copyrighted by the estate of Henry Dreyfuss, used by permission. Reprinted from Henry Dreyfuss, Industrial Designer: The Man In The Brown Suit by Russell Flinchum

, bottom: Contemporary City for 3,000,000 Inhabitants by Le Corbusier, 1922. 2003 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/Fondation Le Corbusier. Used by permission.

: Top silhouette of Chandigarh by Le Corbusier, 1950-1965. 2003 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/Fondation Le Corbusier. Used by permission

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file with the publisher.

Introduction

W HAT DISTINGUISHES GOOD design from bad?

What pool of ideas and examples do architects and industrial designers draw on?

In 1960 these questions would have been easier to answer. Design was still a magic word, and the modern movement associated with the Bauhaus was reshaping the world. Its challenge to architects and designers showed no signs of flagging. Modernism offered clear, serviceable design principles.

But few would claim to be modernists now, especially the architects and designers who enlisted in the modernist cause as students. Postmodern design rejects principles. It is about desire, ambiguity, and chance. This is the Information Age, not the Great Society.

The Bauhaus was a product of its own time and placeGermany between two world wars. Long after its internal conflicts were forgotten, however, it came to epitomize the promise of design. Most modern design ideas predate the Bauhaus sans serif type, skeletal furniture, flat roofsbut the Bauhaus wrapped them up in a compelling package. The Bauhaus stood for design in the public interest, for economy, simplicity and usefulness. It told us what we ought to like.

Designers and architects around the world were inspired by the Bauhaus example. Then they reacted against it. At each stage, Bauhaus ideas about human nature, about social responsibility and taste provided the stimulus.

Modern design aimed to create meaningful order, to fit our physical surroundings to our needs and aspirations. This idea will never go out of date. Who doesnt feel a sneaking affection for Buckminster Fuller? Scolds like Donald Norman and Victor Papanek, insisting that their brand of design could revolutionize everyday life, always find an appreciative audience. Andres Duany, whose New Urbanist recipe promises to turn subdivisions into hometowns, is greeted everywhere as a Messiah. Though moralizing may be out of style, there is no pleasure like knowing best.

Warning against design moralism, Rem Koolhaas studies shopping patterns and designs expensive stores. He praises the imaginative spillover that produced Manhattan. Its true that no rational designer could have dreamed up New York. But New York is not my dream city. Neither is Berkeley, California, where I live. I cant help feeling there is room for improvement. A lot of the best things in New Yorkparks, subways, museumscame from sober design foresight.

In the prosperous period following World War II, Bauhaus-inspired modernists threw themselves into physical and social engineering. But public housing, mass transit and urban renewal did not erase big city problems. We live in a cynical time when taxpayers refuse to pay for public works, when the consumer is king and the mall is his library, church and hobby center rolled into one. What is the designers mandate now?

An answer came from Frank Gehry, Philippe Starck and Ettore Sottsass in the 1970s: design will be personal and idiosyncratic. It can be grandiose. It can be superficial. It should not be boring as modernism often was.

But very few practicing designers get a chance to show off. Most have to find a middle ground between originality and salability. This dissonance between the dream and the reality is nothing new. Design has always been a back-and-forth series of accommodations between the creative impulse and the marketplace. Bauhaus visionaries hoped that, by embracing economic constraints, they could magnify the designers role. Their plain, sensible ideas staved off the pruning impulses of the cost cutters.

I was born in the hopeful era following World War II. I learned that design was going to transform everyday life for the better. My hometown replaced a dark old Gothic high school with a new one that had big picture windows and colorful plastic chairs. I learned that art is hard to understand, and have been trying to understand Ingmar Bergman, James Joyce and Jackson Pollock ever since. Modernists believed that scientific and technical advances produced a break in history: the twentieth century was a radically new era with little to learn from the past. Modernism focused on the infinite promise of the future. That kind of confidence is no longer in the air, and I miss it.

Having visited the Vitra Museum near Basel, where modern design is sold as a luxury item, I take grateful refuge in the Bauhaus ideal. I cant afford what Vitra sells, not even the cheapest things$100 model chairs whose function has been neatly subtracted. Vitra wants you to think of good design as something like Beluga caviar, blessed with an aura of quality, desirable mostly because it costs a lot.

Taste in design does not evolve at a steady pace across the board. Architects, whose style cycles last for decades, havent forgotten modernism yet. Fashion designers, who change every season, forgot it twenty-five years ago. Graphic designers gave up Helvetica and the grid, came back, and have now progressed well into the fusion stage. In this book I talk only about the slowest workers the three-dimensional designers, whose output is all around us and built to last.

The first section, aimed at people under forty-five, tells what modern design is.

The second part contrasts the promise of modernism with its actual results. A lot of modern design, aiming for timelessness, now looks dated. Picking through the Jetsons attic, I try to separate creative design strategies from herd behavior. This quick, hypercritical shopping trip through twentieth-century design history was fun. With the benefit of hindsight, its easy to put modernism to the acid test.

The third part of the book suggests how designers can build on modernism without indulging in retro nostalgia. I propose a marriage between the best postmodern character traitsirony, critical self-awareness, modestyand the best modernist oneshonesty, generosity, and reasonableness.

No one wants to drag design back to 1960. But fifty years of modernist experimentation must hold some lessons for the future. I cant imagine a design curriculum which doesnt stress problem-solving. School is a rational way of transmitting skills and knowledge; modernists wrote the book on rational design.

Next page