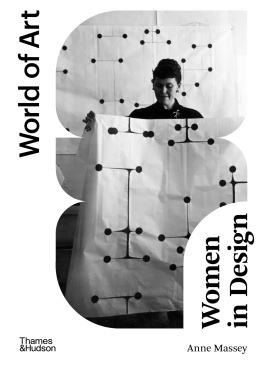

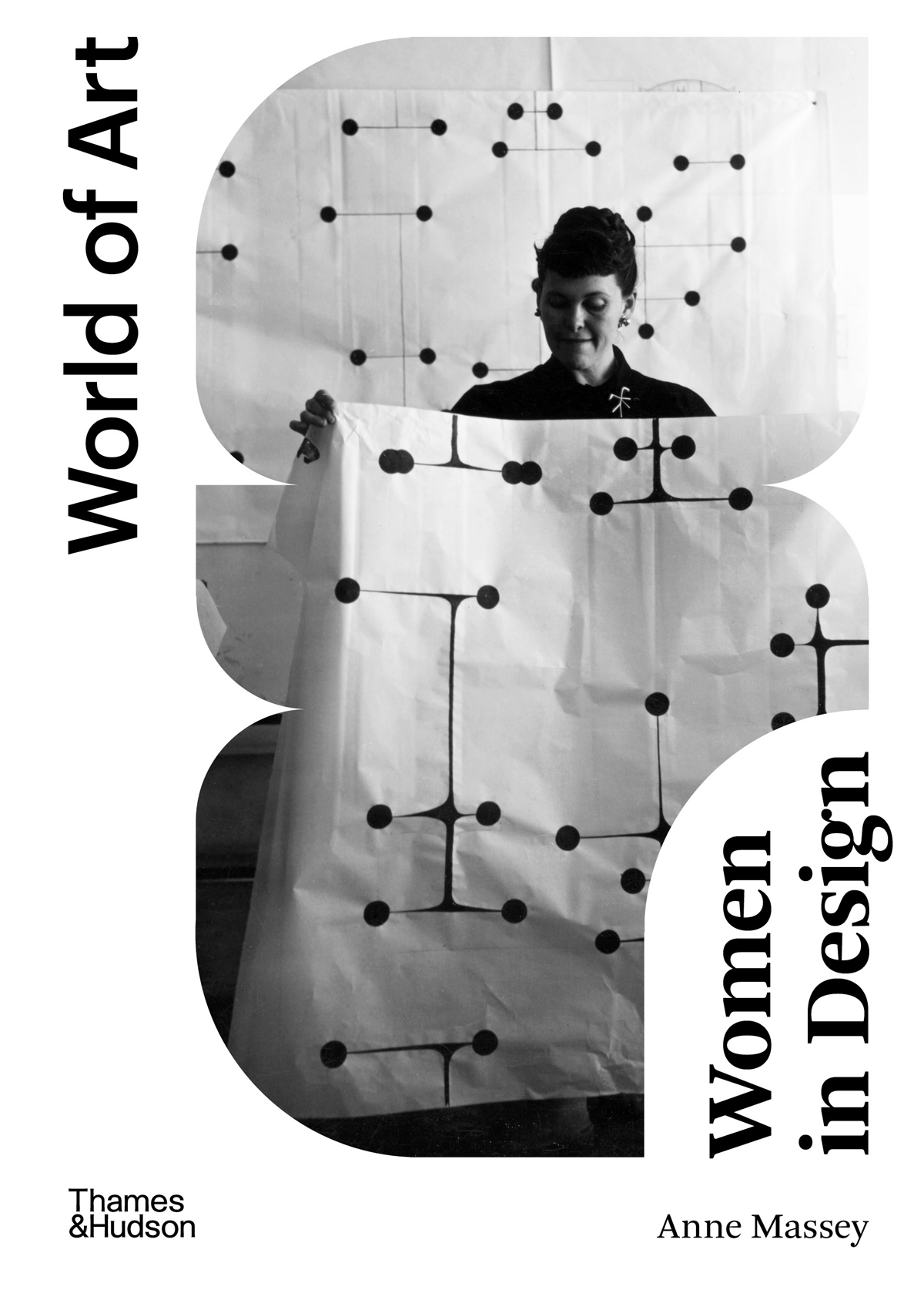

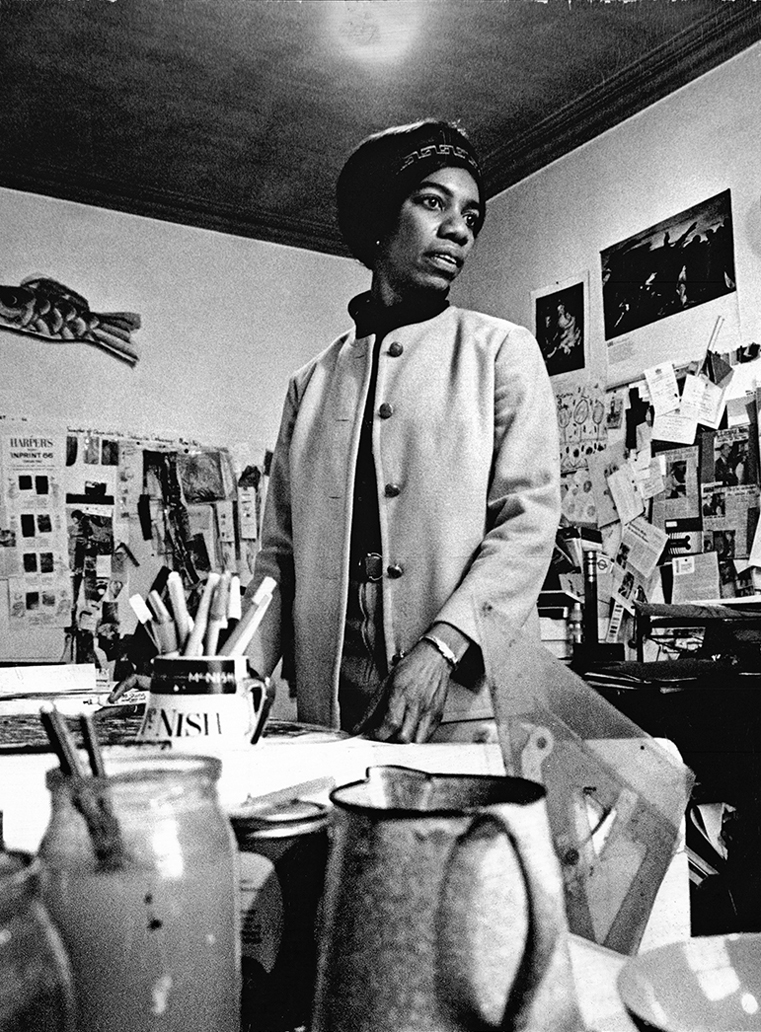

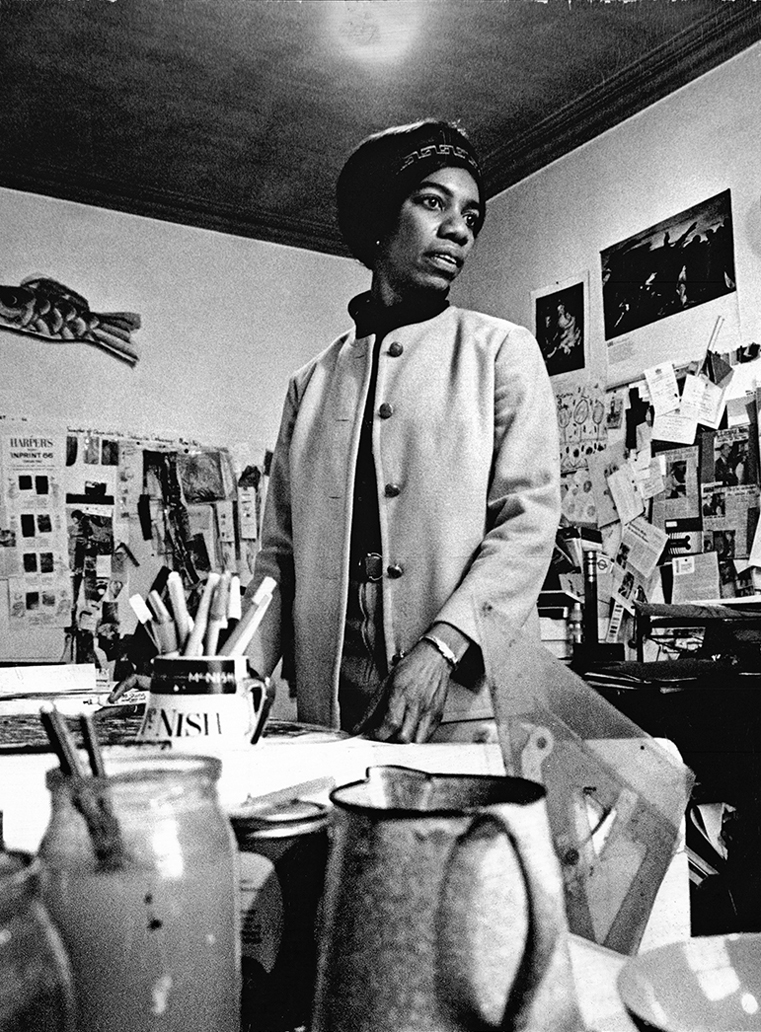

Althea McNish in the Bachelor Girls Room at the Ideal Home Exhibition, London, 1966

About the Author

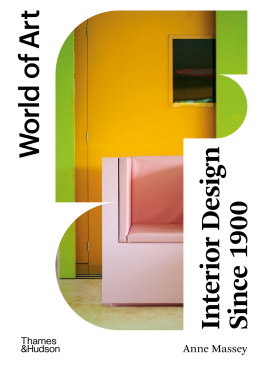

Anne Massey graduated in the History of Modern Art and Design at the University of Northumbria in 1980, and gained her doctorate there in 1984 with research on the Independent Group and post-war British culture. She has written extensively on the history of art and design, and her books include The Independent Group: Modernism and Mass Culture in Britain, 194559 (1996); Hollywood Beyond the Screen: Design and Material Culture (2000); Chair (2011); ICA 194668 (2014); Dorothy Morland: Making ICA History (2020) and Designing Liners: Interior Design Afloat (2021). Her co-edited books include Pop Art and Design (2017) and Design History & Time: New Temporalities in a Digital Age (2019). She also edited The Blackwell Companion to Contemporary Design (Since 1945) (2019) and is the author of Interior Design Since 1900 in the World of Art series.

Contents

Women in Design shines a light on the long-overlooked contribution of women to the history of design. This addition to the World of Art series highlights the pivotal role played by women in the story of modern design, making the invisible visible. For too long this story has been told from the point of view of male protagonists, forming a patrilineage of lone designer heroes. The succession of celebrity designers stretching from William Morris to Walter Gropius, based on the work of Nikolaus Pevsner in Pioneers of Modern Design (1936), now needs realigning. Now is the time to look afresh and include women in a new narrative, and not only as singular creative geniuses or heroines of design. Women in Design takes a more inclusive view of the history of design, looking at both/and, not either/or. The solo designer is included, drawing on the growing literature on women in design that foregrounds biographical accounts of the individual. But work that is the result of a joint endeavour, whether as part of a designer couple or a studio-based team, is also included.

The organizing concept for the book is the pioneering professionalization of women in the world of design. Women in Design looks at the story of womens contribution to the design process in relation to the considerable barriers to entry. At the start of the Victorian era in Britain, married women could not own property in their own right. Women did not have the right to vote or hold government positions. An all-pervading ideology placed women in the home, and the most that many could aspire to creatively and educationally was in the field of amateur handicrafts. Design education and training was barred to many women until well into the twentieth century, as was professional membership of and recognition from professional design organizations. The ways in which women squared up to these challenges and overcame them is the subject of the first chapter.

May Morris, wall hangings for Melsetter House, Orkney, 1900. The linen hangings were commissioned by Theodosia Middlemore for the home she shared with her husband, and embroidered by Morris in naturally dyed wool with help from her client.

Even when women managed to gain entry to the world of design, their work was frequently uncredited or credited to a man instead, and they were paid less than their male counterparts. Women working behind the scenes is the theme for unearths and elucidates the untold story of the female pioneers of modern design. The history of design has been so predicated on the male designer as hero, celebrating one model of what is perceived as good design, that work which is more discursive and decorative is often not included in standard accounts. Modernism, which purported to be eternal and everlasting, was anti-fashion and largely patriarchal, traits reinforced by subsequent histories. The key architect of this modern Darwinism was Le Corbusier, who ridiculed the cheap taste of shop girls for ornament in his book The Decorative Arts Today (1925), as a reaction to the Paris Exposition des Arts Dcoratifs et Industriels. In a highly racialized and sexist statement he described Decoration: baubles, charming entertainment for a savage.... But in the twentieth century our powers of judgment have developed greatly and we have raised our level of consciousness. Our spiritual needs are different, and higher worlds than those of decoration offer us commensurate experience. It seems justified to affirm: the more cultivated a people becomes, the more decoration disappears. Women were identified with decoration, with savages and a lower order of design in the view of Le Corbusier and subsequent modern architects and writers.

. Design activism, whereby women have used design to critique existing power structures, has worked to problematize this type of commercial culture, and is the subject of the final chapter. Starting with second wave feminism, design has been an essential part of protest and insurrection. The reclamation of history is an important part of this; Design History emerged as a discipline in the 1970s, and included a feminist agenda from the beginning. There has also been a growing impetus to study the contribution of women to the history of architecture and environmental design, and the history of art has also incorporated a feminist agenda since the 1970s. These areas are all overlapping and have informed the research for this book. Women in Design relies heavily on the work of others researching in the field, and I am particularly indebted to design historians Judy Attfield, Cheryl Buckley, Zoe Hendon, Pat Kirkham, Jasmine Rault, Libby Sellers and Penny Sparke. The architectural historians Elizabeth Darling and Lynne Walker have produced key works that this book draws upon, as have the art historians Whitney Chadwick and Griselda Pollock.

Women in Design is broad in its approach, and includes architecture, fashion design, graphics, interior and product design. I have included practitioners who are representative of particular fields or themes, and it has not been possible to include absolutely everyone, which goes to show what a rich vein the history of women in design is. Women in Design is structured chronologically, but also thematically, building on the monographic approach to history but augmenting this to reflect the team nature of design production. This is mapped out against a background of political events, socio-economic trends and globalization.

There continues to be a gender imbalance in both the design workplace and design education. Design Council figures from 2018 for the UK reveal that whilst sixty-three per cent of those studying design and creative arts subjects at university are female, seventy-eight per cent of the design workforce is male. Only sixteen per cent of Creative Directors are women and the lack of women in senior positions contributes to a gender pay gap. In the USA, the figures are similar, and until 2018 in some parts of the world women couldnt even hold a driving licence, let alone work as a professional designer. The focus of

Next page