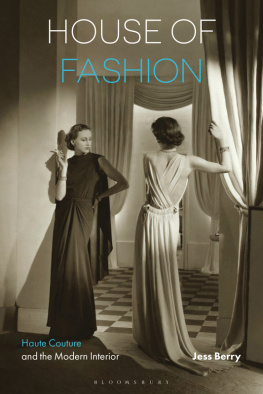

HOUSE

OF FASHION

HOUSE

OF FASHION

Haute Couture

and the Modern Interior

JESS BERRY

This book is dedicated in memory of Bonnie English. Her love of fashion and writing on the subject sparked my initial interest and continues to inspire me to think about the complexities of fashions interdisciplinary histories. I was incredibly lucky to have her as a mentor and a friend. Two other women stand out as my mentors and encouraged me to pursue this work. I would like to thank Dr. Rosemary Hawker, a scholar of enormous integrity and quality, who also happens to have a wicked sense of humor and has shared with me great kindness and wisdom over the years. More recently I have come to know and deeply respect Professor Sue Best for her intelligence, insightful understanding, and impeccable scholarship. I owe a particular debt of gratitude to Sue for giving me the initial push in the right direction to start this book and for very generously reading the manuscript. Her thoughtful feedback has been invaluable. In addition to the unwavering support of these fantastic women, I would like to acknowledge the encouragement of my past colleagues and friends at the Queensland College of Art, Griffith University.

My new colleagues at Monash University in Melbourne have been incredibly welcoming and supportive while I was finishing off this manuscript. Professor Shane Murray, Professor Lisa Grocott, and Dr. Gene Bawden have made my transition to a new working environment an exciting and rewarding experience, and I am grateful for the opportunities they have already provided me with. The design department at Monash is an extraordinarily stimulating place to work, and I would like to thank all of my new colleagues in making it so.

Part of the research for this book involved a trip to Paris to look at the existing spaces of haute couture, old apartments no longer inhabited, and work in archives that house French fashion and interior magazines. The trip was made possible through research funding from Griffith University. I am also indebted to all of the wonderful library staff at La Bibliothque des Arts Dcoratifs, Paris; the Victoria and Albert Museum Archive of Art and Design; and the library and archive, Palais Galliera, Muse de la Mode de la Ville de Paris. I would also like to thank all the organizations and individuals who have granted me image permissions that have made this book so visually rich. Thanks should also go to the little beachside town of Lennox Heads, where much of this writing was done surrounded by beauty.

The stimulating conversations and opportunities that have emerged from conferences that I have attended in recent years led much of my thinking with this book. I would like to acknowledge the importance of being able to talk about this research with Georgina Downey and Peter McNeil at a panel devoted to the interior at the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand annual conference; conversations with Jacque Lynn Foltyn and all the fabulous fashion people at the Interdisciplinary Fashion Conferences in Oxford; as well as the insightful interactions I had with Jennifer Craik, Pamela Church Gibson, Valerie Steele, Adam Geczy, and Vicky Karaminas at the End of Fashion, Wellington.

My deepest gratitude to my fantastic editor Frances Arnold, along with Pari Thomson and Hannah Crump, and the rest of the team at Bloomsbury for their interest and enthusiasm in my work and unwavering help throughout the publishing process. I also thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the initial proposal and completed manuscript.

Lastly, thank-you to my friends and family for their support, encouragement, hilarity, and hijinx whenever required: my inspirational and exciting mother Ruth Berry; Dale Hinchen and Garry Johnston, who are always willing to talk about fashion and the interior over a glass of bubbles; and my very dear friends Andrea Mattiazzi and Victoria Reichelt, who are always there and always brilliant.

It is striking that from its very beginnings, the idea of a house underlies haute couture. When historys first credited haute couturier, Charles Frederick Worth, changed the name of his fashion business from Worth et Boberg to Maison Worth in 1870, he linguistically set himself apart from other fashion merchants with a designation that implied intimacy, privacy, and aristocratic privilege. Where previously dressmakers and tailors would visit their clients in the manner of a tradesperson, Worth devised an elaborate setting for the reception of his creations that enhanced the personalized aspects of his business and obscured the commercial and the industrial dimensions. Despite vast changes to the production and consumption of fashion in the globalized luxury market, this system has continued into the twenty-first century, where the houses designated to be permanent members of the Chambre Syndical de la Haute Couture must continue to keep maison premises in Paris.

In revealing the maison de couture, or house of fashion, as a significant site for the design, production, promotion, and consumption of haute couture, this book foregrounds the interior as an important but often overlooked setting for the spectacle of fashion. The places and spaces of fashion, be they of everyday life, consumer culture, or production environments, inform how fashion is received as a site of adornment, display, and desire. Yet, there is, to date, no singular, scholarly book within the field of fashion or interior studies whose primary purpose is devoted to surveying the historical development of these confluences in relation to haute couture. This is despite the overwhelming presence of the interior in both images and written accounts of fashion from the 1860s onward, as well as the significant interplay that would occur between haute couturiers and ensembliers (interior designers) throughout the twentieth century. This book presents the salon, the atelier, the boutique, and the home as vital spaces for investigation, positioning the haute couture maison in the celebrated realm of the caf, the theater, the department store, and the street, as crucial site of urban modernity and identity formation.

This argument seeks to remedy the situation identified by a range of feminist scholarsincluding Rita Felski, Penny Sparke, and Elisabeth Wilsonthat Rather, the focus of this book differs from previous histories in the larger scope and specificity of the diverse range of interior environments and collaborative approaches under examination.

This book aims to bring the separate histories of fashion and the interior together in order to reveal their confluences and examine their impact on modes of identity formation. It does not claim to be exhaustive, but rather acts as a foundation and reference for further research. Specifically, I argue that two central concerns can be discerned from the coupling of haute couture fashion and the interior. That is, firstly, how the aesthetic stylistic response to modernism within the interior could be leveraged as a mode of social and cultural capital to enhance the fashions, identity, and business practices of haute couturiers; and secondly, how women expressed and negotiated experiences of modernity through their engagement with fashion and the interior. As such, this book offers important historical insight regarding the significant role that the haute couture maison played in female cultures of modernism. It reveals a number of themes that increase our understanding of this subject including, how collaborations between couturiers and ensembliers promoted lifestyles of artistic connoisseurship, the significance of fashion and the interior to the performance of womens lives, and the ways in which the separate spheres of public and private were negotiated and contested.

Next page