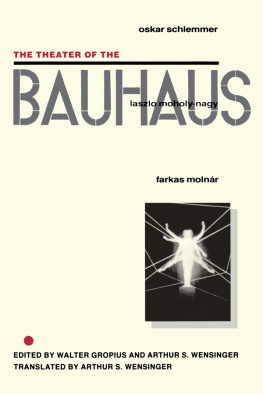

THE THEATER OF THE

BAUHAUS

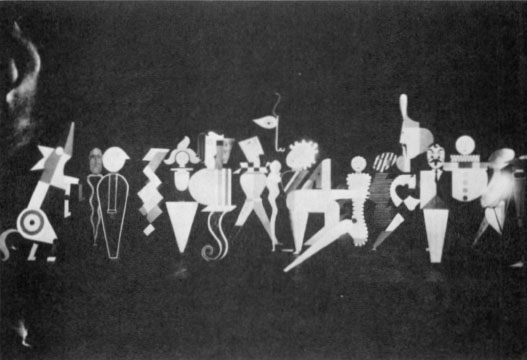

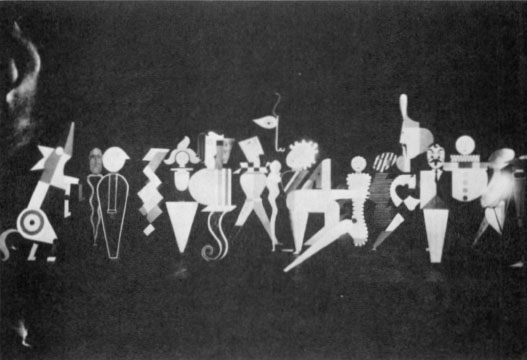

Photograph: Strauch-Halle.

From The Figural Cabinet by Oskar Schlemmer.

Technical production: Carl Schlemmer.

Production with music by G. Mnch-Dresden in preparation. (Figures patented.)

OSKAR SCHLEMMER

LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY

FARKAS MOLNR

THE THEATER OF THE

BAUHAUS

EDITED BY WALTER GROPIUS AND ARTHUR S. WENSINGER TRANSLATED BY ARTHUR S. WENSINGER

Copyright 1961 by Wesleyan University

Statements by T. Lux Feininger are quoted from his article The Bauhaus:

Evolution of an Idea, Criticism, II, 3 (Summer 1960), pp. 261, 272-274; copyright 1960 by the Wayne State University Press; reprinted by permission of the author and the Wayne State University Press.

ISBN 0-8195-6020-0

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 61-14239

All inquiries and permissions requests should be addressed to the Publisher, Wesleyan University Press, 110 Mt. Vernon Street, Middleton, Connecticut 06457. Distributed by Harper & Row Publishers, Keystone Industrial Park, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18512.

Wesleyan Paperback, 1971; second printing, 1979; third printing, 1987

CONTENTS

WALTER GROPIUS

INTRODUCTION

During the all too few years of its existence, the Bauhaus embraced the whole range of visual arts: architecture, planning, painting, sculpture, industrial design, and stage work. The aim of the Bauhaus was to find a new and powerful working correlation of all the processes of artistic creation to culminate finally in a new cultural equilibrium of our visual environment. This could not be achieved by individual withdrawal into an ivory tower. Teachers and students as a working community had to become vital participants of the modern world, seeking a new synthesis of art and modern technology. Based on the study of the biological facts of human perception, the phenomena of form and space were investigated in a spirit of unbiased curiosity, to arrive at objective means with which to relate individual creative effort to a common background. One of the fundamental maxims of the Bauhaus was the demand that the teachers own approach was never to be imposed on the student; that, on the contrary, any attempt at imitation by the student was to be ruthlessly suppressed. The stimulation received from the teacher was only to help him find his own bearings.

This book gives evidence of the Bauhaus approach in the specific field of stage work. Here Oskar Schlemmer played a unique role within the community of the Bauhaus. When he joined the staff in 1921, he first headed the sculpture workshop. But step by step, out of his own initiative, he broadened the scope of this workshop and developed it into the Bauhaus stage shop, which became a splendid place of learning. I gave this stage shop wider and wider range within the Bauhaus curriculum since it attracted students from all departments and workshops. They became fascinated by the creative attitude of their Master Magician.

The most characteristic artistic quality in Oskar Schlemmers work is his interpretation of space. From his paintings, as well as from his stage work for ballet and theater, it is apparent that he experienced space not only through mere vision but with the whole body, with the sense of touch of the dancer and the actor.

He transformed into abstract terms of geometry or mechanics his observation of the human figure moving in space. His figures and forms are pure creations of imagination, symbolizing eternal types of human character and their different moods, serene or tragic, funny or serious.

Possessed with the idea of finding new symbols, he considered it a mark of Cain in our culture that we have no symbols any more and worse that we are unable to create them. Endowed with the power of genius to penetrate beyond rational thought, he found images which expressed metaphysical ideas, e.g. the star form of the spread-out fingers of the hand, the sign of infinity of the folded arms. The mask of disguise, forgotten on the stage of realism since the theater of the Greeks and used today only in the No theater of Japan which as we believe Schlemmer did not know, became a stage tool of great importance in Schlemmers hands. I want to quote a vivid and characteristic report of a Bauhaus pupil of Schlemmers, T. Lux Feininger, who saw with breathless excitement, admiration, and wonder an evenings performance of the stage class in the Bauhaus theater. He writes:

At an early age I had occupied myself intensely with the making of masks in various materials, I hardly could say why, yet sensing dimly that in this form of creation a meaning lay hidden for me. On the Bauhaus stage, these intuitions seemed to acquire body and life. I had beheld the Dance of Gestures and the Dance of Forms, executed by dancers in metallic masks and costumed in padded, sculptural suits. The stage, with jet-black backdrop and wings, contained magically spotlighted, geometrical furniture: a cube, a white sphere, steps; the actors paced, strode, slunk, trotted, dashed, stopped short, turned slowly and majestically; arms with colored gloves were extended in a beckoning gesture; the copper and gold and silver heads were laid together, flew apart; the silence was broken by a whirring sound, ending in a small thump; a crescendo of buzzing noises culminated in a crash followed by portentous and dismayed silence. Another phase of the dance had all the formal and contained violence of a chorus of cats, down to the meeowling and bass growls, which were marvellously accentuated by the resonant mask-heads. Pace and gesture, figure and prop, color and sound, all had the quality of elementary form, demonstrating anew the problem of the theatre of Schlemmers concept: man in space. What we had seen had the significance of expounding the stage elements (Die Bhnenelemente). The stage elements were assembled, re-grouped, amplified, and gradually grew into something like a play, we never found out whether comedy or tragedy. The interesting feature about it was that, with a set of formal elements agreed upon and, on this common basis, added to fairly freely by members of the class, play with meaningful form was expected eventually to yield meaning, sense or message; that gestures and sounds would become speech and plot. Who knows? This was, essentially, a dancers theatre and as such, sufficient unto itself as Oskar Schlemmers genius had created it; but it was also a class, a locale of learning, and this rather magnificent undertaking was Schlemmers tool of instruction.

Indeed it was a treat to watch the precision, aplomb, the power and the delicacy of action. His language, too, although unable to assume command, was an expressive tool. His was the most personal vocabulary I have ever known. His invention of metaphors was inexhaustible; he loved unaccustomed juxtapositions, paradoxical alliterations, baroque hyperbole. The satirical wit of his writings is quite untranslatable.

Schlemmers unorthodox approach to the phenomenon of creation, which expected form to yield meaning, has recently found an eloquent advocate in Sir Herbert Read, the English poet and art critic. He has devoted his book Icon and Idea to the question whether image or thought initiates a new phase of development in human history. He comes to the conclusion that it may well be that the formative artist receives the first message from beyond the threshold of knowledge, which is then interpreted by the thinker, the philosopher.

Next page