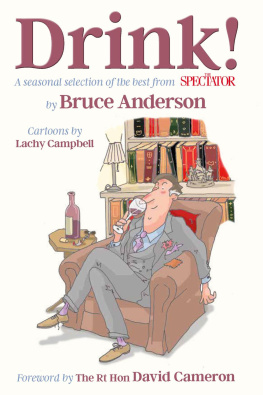

A nyone who has had lunch with Bruce Anderson could be forgiven for thinking that the big mans interest in wine was about quantity, not quality. They would be wrong. While Anderson lunches particularly in the 1990s would often involve him ordering and opening four bottles of wine even before the first one was finished, his knowledge of what he was drinking was always second to none.

And he has never been one of those wine snobs who focus only on France. He would scour wine lists (and your cellar, if you had one) for interesting pinots, rieslings and grenaches from around the world.

On a brief tour of southern Spain he ordered the oldest and most obscure Riojas he could find. One was brown and full of sediment but he pressed on, instructing me to close my eyes and focus on the flavour.

While legendary for vast expenses claims that have tested the patience of newspaper editors for the last four decades, Bruce could always spot a bargain. I recall one lunch where a restaurant had mispriced some 82 Pomerol and he refused to leave until we had finished the entire stock.

Bruces Speccie columns are a great mix of wine, politics, gossip and wisdom. I first met him when he stood in for Sir John Junor who wrote a column for the Mail on Sunday. As a young researcher at Conservative Central Office I used to feed the legendary Junor with tidbits, mostly about Labour splits. In turn, he would feed me with lunch in Kensington High Street where the conversation was all one way: his stories about dealing with Beaverbrook and his undying love for Princess Diana, Margaret Thatcher and, intriguingly, Selina Scott.

After a week Bruce concluded that I was marginally less useless than the rest of Smith Square and so our friendship began.

Bruce is a forest of contradictions. A student Marxist who became a committed Conservative. A harsh critic one minute and a passionate supporter the next. A political obsessive and street fighter but with a hinterland that includes a knowledge of music, opera, art and theatre that is hard to beat.

Bruce has written and said things that put your teeth on edge (and thats putting it mildly), but youre never bored reading his columns or hearing his stories.

His wine columns are one of the things that makes the Speccie unmissable reading and bringing them together in one place is long overdue. Not least because his friends can now access the Anderson wisdom on wine without jeopardising whats left of their livers.

The Rt Hon David Cameron

M ary Queen of Scots had four Marys. The Spectator only has two, but at least neither is likely to be put to death. There is Dear Mary, that wry and sardonic counsellor. No-one since Jeeves has been so adept at navigating through the shoals of social embarrassment. The other is Mary Wakefield, who is a cross between Gerard Manley Hopkins All things counter, original, spare, strange and Little Gidding. She seems wholly suited to a Dearly Beloved, via media Anglicanism, redolent of scholar gentlemen doing good works in country parishes while also acting as beacons of humane studies and, of course, basing their services on 1611 and 1662. Her debut in The Spectator was an arabesque of delicious reportage about a different sort of service. It took place in Holy Trinity Brompton, where there was a sermon about hamsters while yuppies serenaded God to the raucousness of electric guitars. Her gentle, more-in-sorrow-than-in-anger prose only highlighted the comprehensiveness of the intellectual filleting. Yet Mary has left for Rome, relieved that she no longer has to worry about the Church of England. Were I an Anglican, I would regard her departure as a grievous loss. The salt is losing its savour.

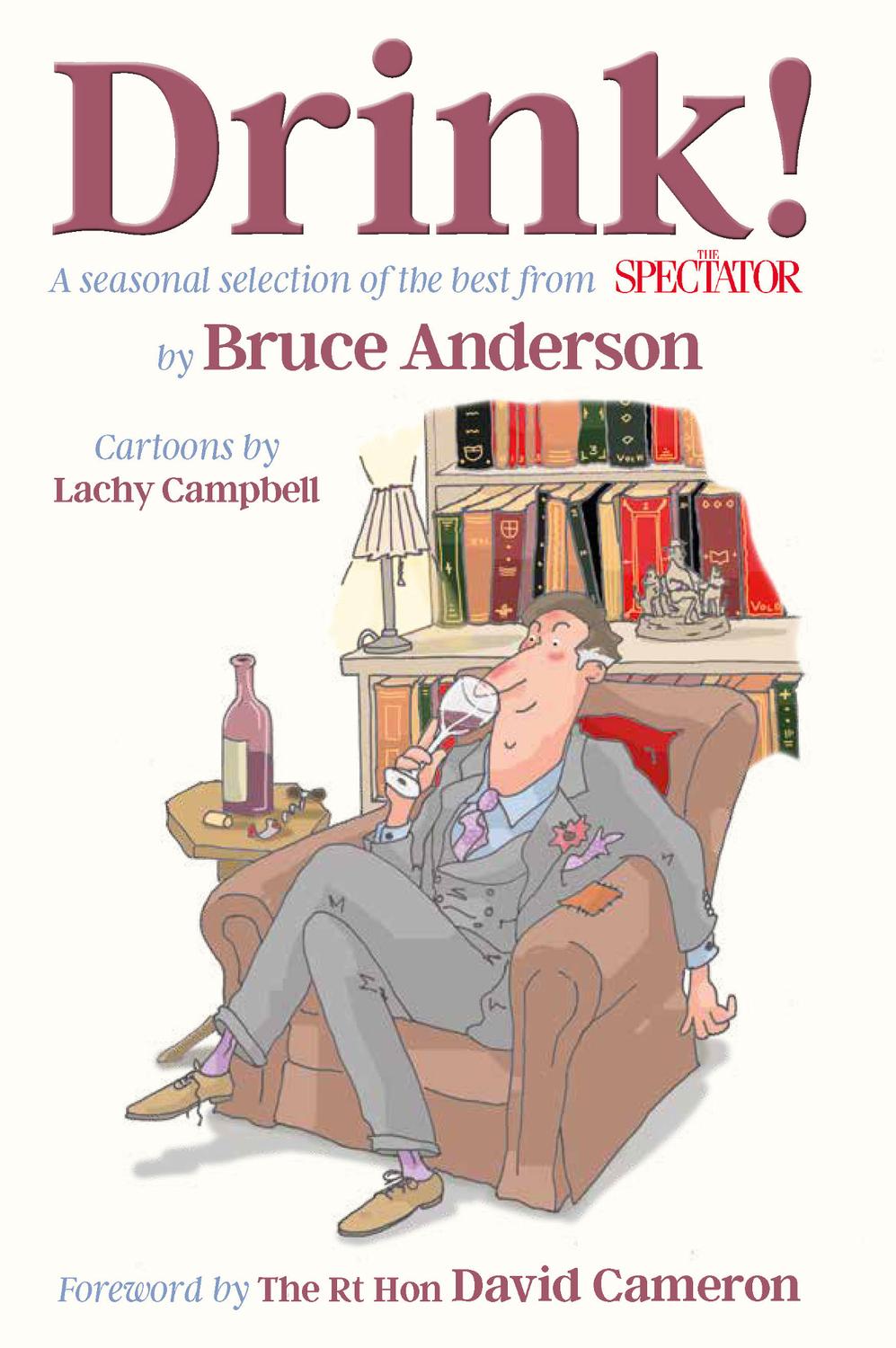

She is also responsible for all this. Around a decade ago, she decided that I should write a wine column for The Spectator. I protested that I knew nothing about wine. She demurred. A demurral from Mary is a formidable experience. She is not exactly Eve or Delilah. Nor is she Beatrice, or Violet Elizabeth Bott. As a literary model, it is more a matter of Elizabeth Bennet. But she knows how to get her way. I insisted that on wine, although I might have acquired a certain amount of bottle-learning, I had little book learning. Nor do I have an expert palate. She brushed all that aside. We agreed that the column should be entitled Drink rather than merely wine, and that I should weave in other topics. I do not think that either of us realised just how far that warp and weft would reach. Anyway, it was her idea. She is to blame, or even, perhaps, praise. With the exception of that two-hours-before-the-deadline moment, known to all hacks, when everything seems dark and doubtful, it has been fun to write. Somehow, the darkness always dispels. I hope it has also been fun to read.

Bruce Anderson

M y friend Jonathan Gaisman recently gave rise to a profound philosophical question concerning wine. Jonathan is formidably clever. He has a tremendous reputation at the Commercial Bar. Although he brushes aside any compliments from the unqualified, there was a recent case Excalibur where his performance won the awed approval of lawyers to whom even he might concede quasi-peer status. They aver that his preparation was exemplary, his cross-examination ruthless and relentless; his triumph total.

That said, he is anything but a monoglot lawyer. Not only a music lover but a musicologist, modesty alone would prevent him from claiming that Nihil artium a me alienum. Among the minor arts, he is a practised oenologist. But he is also thoughtful and combative on the subject of religion, on which he and I have had many exchanges. In a recent issue of Standpoint, he wrote an essay, The devout sceptic, which came close to convincing this devout atheist. Almost thou persuadest me to be a Christian.

Almost, but there is a basic problem. It is not clear to me that Jonathan himself is a Christian. I have argued that no one can call himself a Christian unless he believes not only in the Incarnation but also in the literal truth of the Resurrection. If it is not true Christ died on the cross and was raised from the dead, Christianity is meaningless. This point irritates Jonathan. He does not see why I should prescribe rules for a club to which I do not belong. But I would retort that without the Resurrection, his version of Christianity has no theology and no historical continuity. It is merely a matter of aesthetics and ethical aspirations.

Jonathan once asked me whether I believed that there were mystical truths. Caught off intellectual balance, I replied: No. I am still trying to decide whether I agree with myself. What is truth? said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer. It depends what you mean by truth, C.E.M. Joad would have asserted. I will be temerarious enough to assert that truth is only a useful concept if it relates to a subject matter that is verifiable. So mysticism may be beautiful. That does not make it truthful.

It is so tempting to conflate truth and beauty. Titians Assumption in the Frari, the Mass in B Minor, Durham Cathedral. Surely none of them could have been created without faith. As ones soul soars in response to their sublimity, it seems churlish not to genuflect to that faith.