Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Joanne

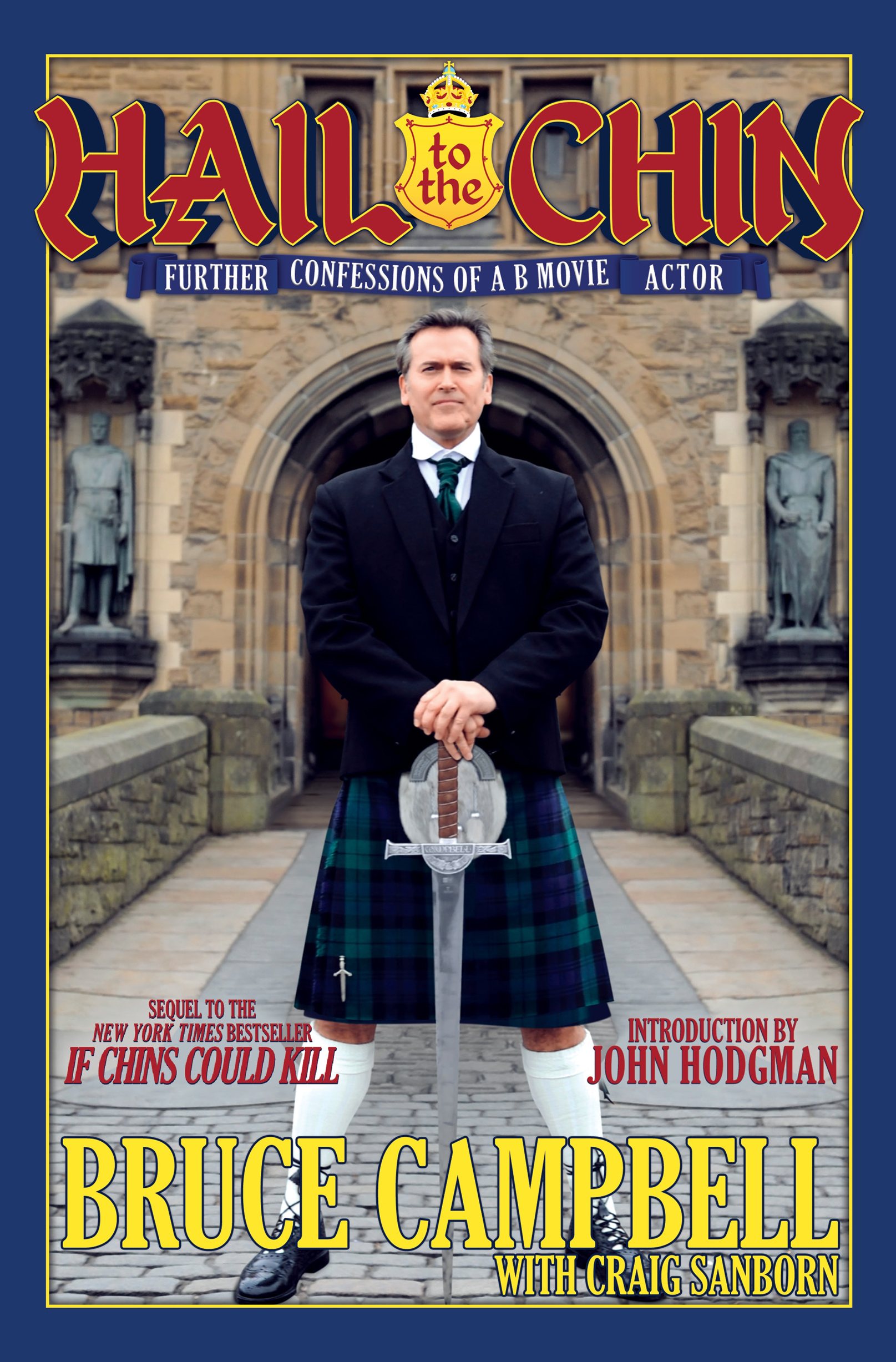

BY JOHN HODGMAN

When I first got access to decently fast internet, I did what everyone did: I typed in my own name. It was twenty years ago. I was an assistant at Writers House, an accredited literary agency in New York City, and we had just gotten a T1 line. Prior to this my internet experience had been walled in by the slow, screeching garden of dial-up AOL. Now I had the World Wide Web indeed, the world on my desktop. And with new and remarkable speed, Alta Vista told me I did not exist in it.

The next thing I did was to type in Bruce Campbell.

I knew about Bruce because in high school Nicholas McCarthy showed me The Evil Dead. Then in college, I watched The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. with Jonathan Coulton before it was briskly cancelled. Bruce was already a cult celebrity by this time, but it is both important and difficult to remember that this time, before Internet had meaningfully saturated our lives, cults still met in the dark. Before YouTube, social media, even blogging, nerds only found their fellow cult members in slow motion, via letter columns and yearly regional conventions. They had not yet mobilized via the Web into a massive, cranky, demanding, and inspiring consumer and cultural force. Since I didnt exist on the internet, I wanted to know if there was anyone else out there like me. So like any nerd, I typed in some code words a single ping into all that darkness and waited for what echo came back. What came back was Bruce.

Along with a half dozen Bruce Campbell fansites was bruce-campbell.com. It didnt look that great. The design was unflashy and homegrown. There may have been some Comic Sans in use. But because it was so cheesy and charming and great at the same time, I knew it could only be real Bruce behind it. And it was. I am usually right.

Aside from posting the dates of his appearances at upcoming horror movie conventions, Bruce told stories on his Web site. He wrote about the tedium of leaving his family to live in Mexico for months to shoot his few scenes in a movie that no one would remember (unless you happen to be the nerd who runs a Tumblr devoted to Tom Arnolds interpretation of McHales Navy ). He wrote about the sweat and fake blood that he and Sam Raimi and Rob Tapert had to pour into The Evil Dead to get it, impossibly, made. He wrote about the strangeness of being like unto a God within the hotel ballroom that is hosting this small horror movie convention, only to step into the hotel lobby, a suddenly anonymous, unfamous Shemp. He wrote about a fox he saw one day when he went out for a bike ride.

I thought it would all make an interesting book. (Well, not the fox part, though I still love that story. There is something unmistakably Bruce his openness to the world and small pleasures in his turning to the Internet to report that he saw a cool fox that day). I clicked on the link that was an e-mail address. I typed a few more words into the darkness, and then forgot about it. Until Bruce wrote back.

Of course Bruce checked his own e-mail. At least then he did, because he could. He knew how few of us weirdos were out there enough to delight with his Web site and fox tales, but not enough to bother him with too much attention or money. I did not understand this at the time. I thought I had hit a gusher. Someone had just sold a Whoopi Goldberg book for almost a million dollars. And since I had the cultural face-blindness of the young nerd that could not differentiate between the fame of Bruce Campbell and Whoopi Goldberg, I thought Bruces sudden blind trust in me was not only A) astonishingly kind, but also B) well-placed, and C) the start of a very successful career as a professional literary agent. Only A was true.

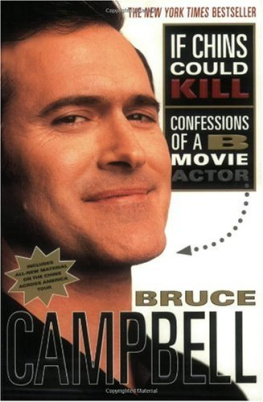

Bruce mentioned casually in his own afterword to If Chins Could Kill that it was not easy to find a publisher for that book. I will be less casual: it was rough. Bruce wrote an amazing proposal along with the help of his incredible assistant Craig (who I am thrilled to see back in the byline with this book). But as I called around, I realized I had underestimated how many New York book editors loved Army of Darkness; and equally, I underestimated the sniffy contempt so many New York book editors would have for those nerds who did. Army of Darkness was a cult movie, beloved by a few weirdos, but dismissed by the mass mono-culture that could only be reached by big publishers and studios and record labels and broadcast TV, the same mass mono-culture that was the only way to make money and which would go on forever and ever. The rejections poured in, each a humiliating gut punch: I was not only failing, I was failing my hero.

In 1999 or 2000, I went with Bruce to a horror movie convention at the New Yorker Hotel near Penn Station. Conventions were still like Bruces old web site: small, a little ramshackle, and summer-campy. No one was coming to launch a major media property there. It was weirdos who loved weird things, including Bruce Campbell. Seven hundred or so people crowded into the room for his Q&A. Bruce answered every question. He reassured the crowd that they should not be worried: his old high school pal Sam Raimi was the perfect person to bring Spider-Man to the screen. He encouraged them to get out there and make movies just like he and Sam had done. He pointed out that the most profitable movie of that year had been The Blair Witch Project, which had been self-produced, shot on consumer grade equipment, and home-publicized using the Internet. Things are changing, Bruce pointed out.

I had sent out a videotape (a videotape!) of an appearance like this, from an earlier convention, with each proposal. Who knows if the publishers watched it, and if they did, whether they were impressed. All of them rejected the proposal except one, Barry Neville, of St. Martins Press.

Barry was there with me now at the New Yorker Hotel. It was the spring before If Chins Could Kill would be published. We watched the fans line up, hundreds of them, to bring their T-shirts and Ash figurines and bared chests for Bruces signature. In a few months they would come back with books in their hands. This would happen in dozens of cities across the country. Im sure its sales did not rival Whoopi Goldbergs, but it was enough to put it on the New York Times bestseller list. And I guarantee it made the publisher a profit, because I know what the advance was.

Barry was brave to have fought to acquire the book, but his was a bravery of love, not of business. Neither of us knew the book would succeed. We only guessed based on what Bruce had told and shown us: you can cultivate a good and profitable artistic career by knowing your audience and keeping them close; that soon we would all have to do that, because mass mono-culture was largely not going to exist anymore; and that Sam Raimi would do a good job at Spider-Man. By the time Spider-Man opened to almost 100 million dollars in one weekend, it was becoming clear: what mass culture would remain would be nerd culture.

Was Bruce ahead of his time? Yes. But the success of Chins, like all his successes, stems more from the fact that he is an old-fashioned good dude. Before he signed with me I had to meet his manager. It was a hot summer Sunday. He was in town for some premiere, and I had just bought a blazer to make myself look like a grown up. It just made me sweat, and that sweat grew cold in the a/c of the Au Bon Pain where we sat as I tried to figure out how I was going to convince this man to put his client into my soft, inexperienced hands.