Title Page

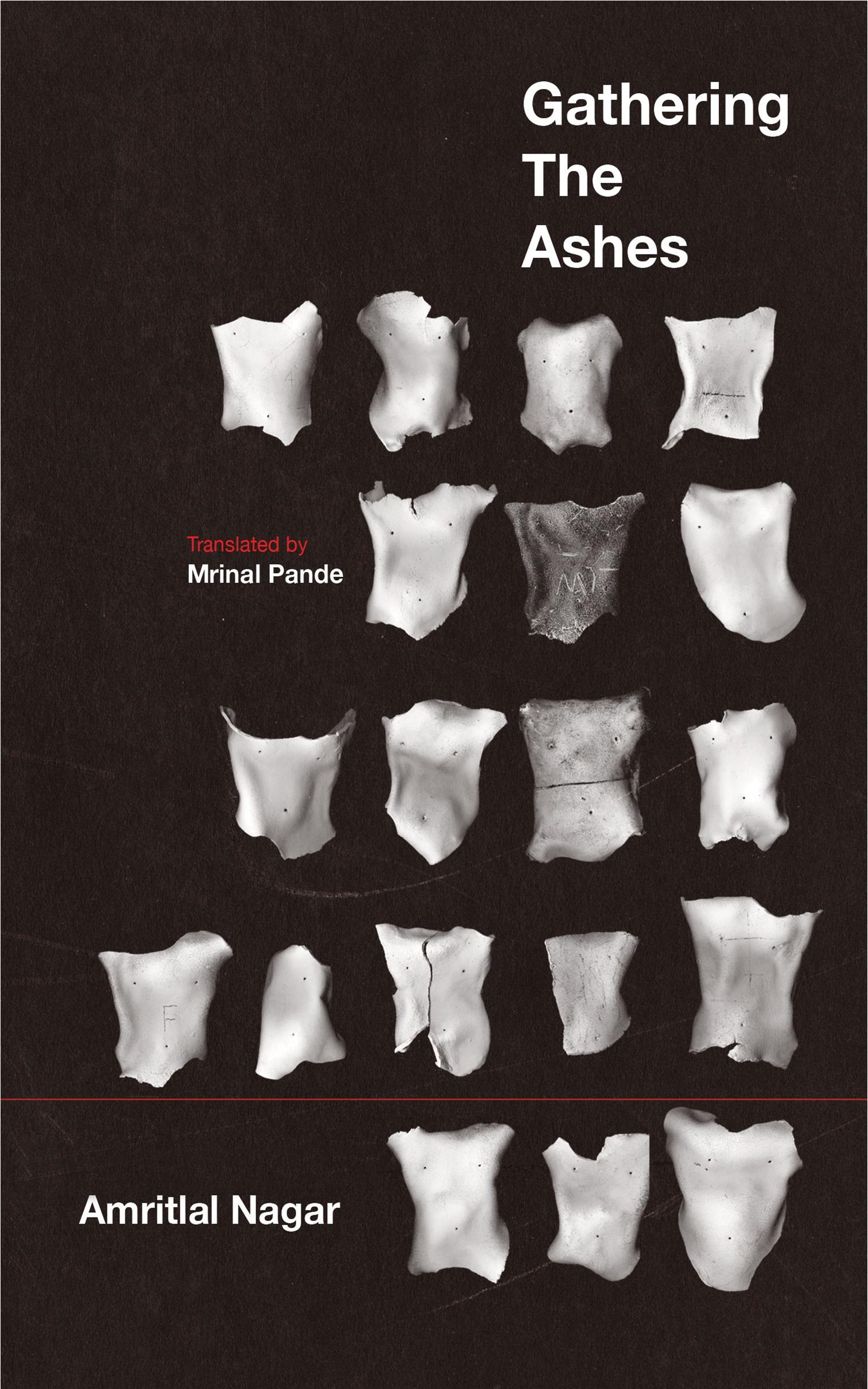

Gathering The Ashes

Amritlal Nagar

Translated by

Mrinal Pande

Dedication

To all those who have fought successfully or otherwise, for their rights and India's freedom

Contents

As I began collecting information for a novel I wished to write about the ghadar , the great public uprising of 1857 in Awadh, I began to feel increasingly dissatisfied with the material that came my way. It was evident that my task would remain incomplete until I visited the actual area where the ghadar had taken place a hundred years ago, and gathered the memories and local legends from authentic local sources that were fast fading into the mists of time. Since so little about the ghadar has been written down by our own people, the only way to understand the historic event as the local public experienced it, was to follow the orally transmitted memories and legends that had survived among ordinary families and clans in the countryside.

Therefore in 1957, as the nation was getting ready to celebrate the ghadar s first centenary, I began to think of travelling through rural Awadh to gather memories of the uprising that had been transmitted over the years. I felt the same sense of duty and veneration that families carry as they set out to gather the ashes of a dear departed one.

There was one problem though. The extensive travelling required for this task needed resources that were beyond me. Here I was helped greatly by Bhagwati Sharan Singh, director of information for the government of Uttar Pradesh and his departmental colleagues. Together, they facilitated my travels and meetings with people. Bhagwati bhai is a close friend and I am sure, expects no effusive and formal expressions of gratitude from me.

I began writing this book on 21 July 1957, and completed it within three months, on 16 September. Gyanbhadra Dixit wrote out the entire manuscript for me, by hand. My younger brother, Madan has managed to reproduce an enlarged portrait of the late Begum Hazrat Mahal, using a very small and faded photograph I acquired through her great grandson and my dear friend, Sahibzada Kaukab Qadr. I am truly indebted to all of them.

Amritlal Nagar

The Chowk

Lucknow

(The writers preface to the first imprint of Ghadar Ke Phool published by the Publications Division of the Department of Information , Government of Uttar Pradesh in 1957-58)

The route adopted by Amritlal Nagar for his travels does not follow the order of events in 1857. The ghadar had first erupted in the army camp in Meerut and then spread simultaneously towards Delhi and Lucknow, the capital city of Awadh. When Lucknow was reclaimed by the British after a long and bloody siege, the rebels fled to the countryside of Awadh where the battle continued for almost a year before the revolt was finally quelled. For various reasons, Nagar began his travels in the reverse, starting with the rural areas of district Barabanki. It is only in the last chapters that he talks at length about the events surrounding the ghadar years, the decline and fall of the nawabi regime of Awadh with its old hybridized culture and the rise of a new anglophile elite led by the now all powerful British in his beloved city of Lucknow. It was a city with which he had a very long association, and where his many friends from various communities and different strata of society had been helping him gather rare material for years.

During the ghadar years, Barabanki was one of the four districts in the Faizabad division. It is a fertile area fed by the rivers Gomti, Ghaghra and Kalyani. According to the 1871 census, the district then had thirteen large towns and four tehsils or subdivisions. It had fifty-three major talukedars who headed the rural socio-economic infrastructures and commanded a lot of respect from farmers in their areas. As a class of rural elite, the talukedars of Awadh were created by Saadat Khan, the founder of the nawabi dynasty of Awadh and a representative of the Mughal king in Delhi. Khan opted for a hereditary band of revenue collectors from among the major local landlords and later also entrusted them with the task of maintaining law and order in their allocated area. Given the immense powers they now came to exercise, the talukedars were frequently also referred to as raja.

Around the time the Nawab of Awadh was dethroned by the East India Company, these rajas owned half the land and over sixty per cent of the villages in the area, and were contributing ninety per cent of the assessed revenues to the royal exchequer at Lucknow. The clans the talukedars belonged to, had come into Awadh in waves all through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Once they had settled in, they invited their clansmen to join them, providing them with ample farming land and strengthening the kinship ties further by marrying into their families. The loyal band of brothers thus created over generations formed a security ring around the talukedars and members of this charmed circle were ever ready to go to war on behalf of their raja.

In addition to powerful talukedars, there were also 5397 wealthy zamindars and small cultivators in this region. They employed some 1354 landless labourers, mostly from the dalit communities to work in their farms. All cultivators paid a rent to the talukedar and had the right to mortgage their land in times of need, and then the person to whom that land had been mortgaged, began paying rent to the talukedar. Since the higher castes considered it shameful to hold the plough, they mostly found landless men from lower castes to till the farms and sow and reap their crops. For this, often a big loan was paid to the mans family who then became a bonded labourer for the loan giver. It was an exploitative system since all cultivators were dependent on the raja and their tenant farmers for vital livelihood. But it protected the small farmers and landless families against even more cruel moneylenders and the corrupt and exploitative officers of the Crown.

After the rebel forces lost Lucknow, the rebel leader-in-chief, Begum Hazrat Mahal issued a fervent appeal for help to talukedars in the rural areas in the name of her infant son Birjis Qadr who had been declared the regent by rebel leaders in Lucknow. By now the peasantry had also begun to exercise a great moral pressure on the rajas for throwing caution to the winds, begging them to come out in defence of Awadh and its infant nawab.

Dariyabad, the then district headquarters, was the scene of one of the major battles in rural Awadh. After the natives were defeated, the victorious British forces mercilessly pillaged and destroyed Dariyabad. Several minor battles were also fought in the nearby villages of Bhitauli and Ram Sanehi Ghat (also known as Rudauli), and the British armies, led by Sir Hope Grant finally got the rebels to surrender in Nawabgunj. Major rebel leaders like Nana Saheb and Begum Hazrat Mahal, however, managed to escape into the adjacent state of Nepal along with a few loyal armed men. After the ghadar, the district headquarters were shifted from the ruined town of Dariyabad to Nawabgunj, and ultimately to Barabanki.

Present-day Barabanki district has 1.68 per cent of the total population of the state of Uttar Pradesh, two parliamentary constituencies and seven state assembly seats. The rebel genes obviously got passed down across generations because six decades later, people from this region joined Mahatma Gandhis 1921 Civil Disobedience movement. Many protesters were jailed when they actively protested against the Prince of Waless visit to India. Among them was Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, from the well-known Kidwai clan of Bhayara village, who later rose to be a major public leader in Independent India.