To June Hyde, with gratitude

When you meet a man who talks like that you should run for your life.

Fifth victims brother

He is our dearest treasure on earth and we commit him to the God of all Graces.

John Haighs parents

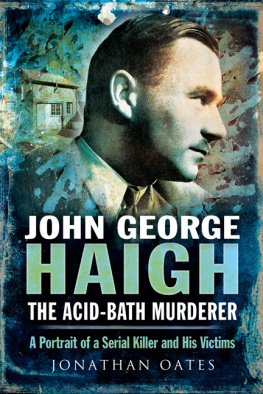

John George Haigh. (Dunboyne, Lord (ed.), Trial of John George Haigh )

Contents

O n what was to be her last day on earth, Mrs Olive Durand-Deacon sat down for breakfast as usual at eight oclock at the Onslow Court Hotel, South Kensington. It was Friday, 18 February 1949 and the widowed Olive, who would have been 70 the following year, had been living at the Onslow Court, a residential hotel for the wealthy retired, for the last six years. The loneliness and shock of finding herself a widow at the age of 54 was partly tempered by her holding stocks and shares worth 36,000 (nearly 900,000 today). The companionship of her new friends and fellow residents at the hotel, particularly Mrs Constance Lane, who sat at the table in the dining room to her left, and Mr John Haigh, who sat at the table to her right a comparative newcomer as hed only lived at the hotel for the last four years was also a comfort.

The only thing unusual today was John Haighs empty table. Admittedly, he had to come down from his room on the fourth floor but as a rule he was there before Olive, ready to do his rounds, as he called his business trips. She was concerned about this and hoped he hadnt been taken ill in the night. Although he was a young man of 40 she thought he overdid it, careering around the country in his lovely Alvis motor car, and he sometimes looked quite worn out in the evenings when they sat down to dinner.

But, however tired John might be, there was always a smile on his face and time to exchange pleasantries about the day. Olive was surprised that a catch like him hadnt been snatched up years ago by some lucky girl and spirited off to a leafy suburb in the home counties. He did occasionally bring in a girl, whom he called Barbara, for afternoon tea, but as nice as she was she seemed young enough to be his daughter. He hinted to Olive over coffee one evening at the hotel that there had been a wife at some stage but never said more than that.

Sometimes thered even be a little prize for Olive or one of the other good ladies in the form of a piece of jewellery or bottle of perfume, something they couldnt get with rationing still in force after the war. They came at a price, of course, like the lovely crocodile handbag hed brought her a year ago, charging only a modest 10 when in the shops it would be a lot more, if you could get something of such quality at all. And there was the exquisite blue sapphire and diamond ring she wore without ever telling a soul how much she paid John for it.

Then, to her relief, she spotted him on the other side of the dining room, stopping at a table and pulling out a long box with a watch or necklace wrapped in tissue. The expression of sheer delight on the face of the lady on the receiving end said it all, and she was gazing up at him and mouthing a question at which John was shrugging his shoulders and smiling his usual wonderful smile.

Perhaps if Olive were thirty years younger she might have designs on John herself, but at the age of 69 all that was over now and so what was the point; John Haigh, with his slightly high voice and petit bourgeois manners, would not be suitable for Olive Durand-Deacon, the widow of an army officer, in any case. But whatever you said about John, he did bring a lot of happiness to everyone at the hotel, and she for one wouldnt hear a word against him.

Ah, Olive, good morning, he greeted her as he passed her table, almost as if he were surprised to see her despite going through this ceremony every morning.

Good morning, John, looking after us all as usual I see, she replied with a regal nod of the head. People said she looked like Queen Elizabeth, who with her husband King George had looked after them so well during the war. Although not a vain woman, Olive liked to think she at least dressed like the queen and, while twenty years older, agreed that, well, there was something a little royal about her.

John hesitated before sitting down at his table. We must talk about your nails today, Olive, he said.

It would be a pleasure, she replied, beaming.

She looked back at him as he poured his coffee and spread a piece of toast. Her examination of him was no intrusion because the single tables in the dining room at the Onslow Court were arranged and angled each on four tiles of floor space, like pieces on a chessboard, to maintain at least the pretence of privacy. The hotel was perfect for them, near the Science Museums and the Victoria and Albert, Harrods and the shops, and of course the Royal Albert Hall at the top of Queens Gate for concerts.

Olive still worried about John even though he was now safely eating his breakfast. Despite wearing his usual immaculate suit, white shirt and silk tie, he looked weary and a little beaten. The hair was oiled and carefully brushed back and he was clean-shaven apart from his small moustache the waft of Brylcreem and aftershave hit you as he passed. But there were bags under the piercing blue eyes and his effusive manner had gone over the last week it was Friday and she hoped he would be more himself over the weekend.

Whatever was on his mind that morning, John was deep in thought until hed finished his second piece of toast and drunk his second cup of coffee. Then he came over to Olives table and pulled up a chair to sit beside her. He put his hand over hers on the pristine white tablecloth and patted her ringed fingers, something hed never done in all the time theyd known each other. Now Olive, he crooned, we have business to do and I have everything planned for you.

But if shed had an inkling of what John was planning for her that Friday afternoon, Olive would have run for her life.

J ohn really had arranged everything, down to the last nail. The business they were discussing was the manufacture of artificial fingernails. Olive Durand-Deacon had a box full of them in her room, and when she heard that John was an inventor and the director of a light engineering company, she asked if he might be interested in a little business venture: he could manufacture the nails and she could design and market them.

Hed told her about the machine he wanted to market that threaded cotton through needles and a wonderful toy fort where all the soldiers moved around on a pulley system. Shed bought a couple of his handheld electric fans, but these had gone wrong rather soon, which embarrassed her because shed bought two more and given them to friends going to Australia on a new ship, and she hoped these hadnt suffered the same fate.

But the fingernails were all her idea after shed cut out pieces of newspaper and laid them to be painted on her own nails. While her marriage to a war hero with the Military Cross had been varied and fulfilling, she always harboured the idea that at heart she was a businesswoman. With the Second World War now four years behind them, women were starting to think how they looked again, about luxuries like decent hair and nails.

And John Haigh, despite the expensive cars, the suits and the silk ties, and despite, as he told her, being a solicitor specialising in probate matters in a past life, could himself do with a new business venture right now. Because, not for the first time in his life, he was financially embarrassed or, to put it less kindly, flat broke, down on his uppers, skint however you wanted to describe it.

Next page