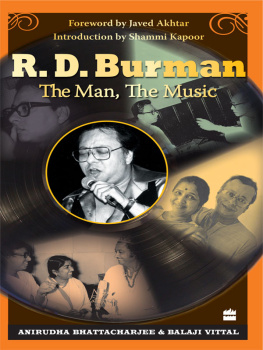

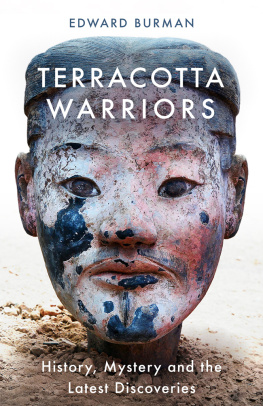

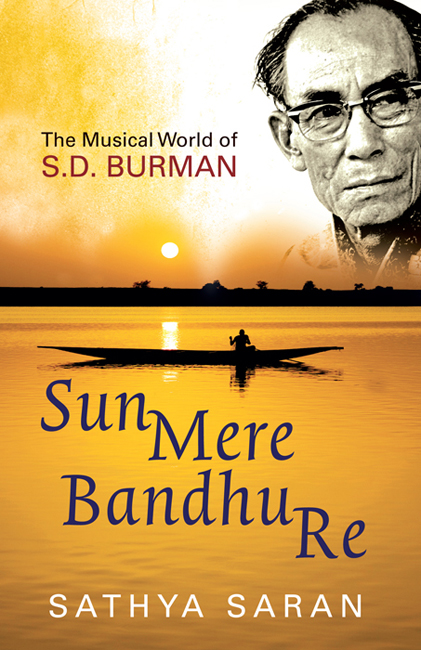

Sun Mere

Bandhu Re

THE MUSICAL WORLD OF S.D. BURMAN

SATHYA SARAN

HarperCollins Publishers India

To my sister Nithya.

Because we grew up singing many of the songs in this book.

Contents

Afterword

Sachin Dev Burman: The Man behind the Legend by Moti Lalwani

One thing usually leads to another. The thread of destiny unravels in surprising ways, sometimes telescoping the past and present into a concrete moment.

I have never met S.D. Burman. I know his songs of course, have grown up singing them to myself. I had seen the rare picture of him somewhere, and held the impression of a calm, spartan face that could have been etched in solitude by a calligraphists pen.

Beyond a chance second-hand encounter with the composer through Abrar Alvi while researching my book on Guru Dutt, I knew nothing about S.D. Burman. And Alvi revealed him only as a gentle soul, possessive about his paan and careful with his money not much to build an image from.

But one thing led to another. A young man who worked in the same building I used as an office for a while came up to say that his father had read my book on Guru Dutt. He wanted to know if I would take on the writing of a biography of S.D. Burman. His father, the young man continued, was a huge fan of the music director, and had collected clippings published about him for the past few decades, which he was willing to hand over to me.

And so it was that I met Moti Lalwani who came bearing his treasure trove. A meeting that resulted in two bulging files in my custody.

This was followed up by a series of interviews that had been conducted for the four fan-page web sites he administered, and an offer to continue to do interviews of prominent players in S.D. Burmans musical world. Of course, I gratefully accepted.

For almost four months after this, I refused to look at the material on hand. Material that kept coming in, in the form of fresh interviews, and relentlessly stared at me from my inbox everytime I logged on. When I finally began to read, it was like entering a labyrinth. I could so easily be lost in this uncharted territory, where voices spoke from every direction; some echoing, some contradicting one another. Despite so many voices speaking about him, I could find S.D. Burman nowhere. The man was missing.

Adding to my confusion was a package that landed on my table one morning. From Bangladesh. A book on S.D. Burman by a venerable researcher of the composers work, H.Q. Chowdhury.

My heart sank. Was I heading to a dead end? Was there place for a second book? What could I say that was new about a man I had never met or known?

It was S.D. Burman himself who came to my rescue. His slim autobiographical note, Sargamer Nikhad, written with simplicity and a charming lack of self-consciousness was the first real insight into the person I had been looking for. His stories of his youth, his description of his interactions with those who mattered to him in his musical journey through life gave me the clue on how to shape his story.

I put aside everything I had read as notes and interviews. I listened to the songs, I let myself listen to the world around me as someone who heard only the music in every sound.

And the book began to take shape in my mind.

I listened to the music of the birds, to the beat of a butterflys wings as it flitted past my window. The rat-a-tat of the local train, the shouted cadences of the fruit sellers voice, the spoon hitting the side of the pot in the kitchen I imagined a musician listening to them and capturing the music inherent in every sound.

And destiny took me back to the days when I walked barefoot in the grass, chasing dragonflies, or lay in the shade of a spreading rain tree watching alternately the clouds or the brown tufts at the ends of the leaves of grass waving in the breeze while far away a man selling mud violins played a tune I knew the words of.

It was easy then to blend the real with the almost real. To let imagination colour the calligraphists portrait in the shades of music.

By the time this book went into edits, another book on S.D. Burman had come out, this time by an Indian, by someone who shared the surname. But by now I was no longer worried about the content. Another book wasnt going to make a difference because I had decided on a new approach to the narrative altogether.

This narration of S.D. Burmans life follows his journey through it and through his music faithfully. There is nothing in the book that has not been documented elsewhere in print or recorded through interviews for this book. It is only in the telling of the story that I have, like the subject of this book, let myself roam free. Just as he would take the seven notes of music and spin out of them an endless fabric of songs, I have tried to take the many facts and milestones of his life and weave a tapestry that reveals in its intricacies the genius of a man whose life was simply dictated by music.

In doing this, I hope to present S.D. Burmans amazing story not just to those who have thrilled to his songs, but to a generation that can learn the blessings of a way of life dedicated so passionately to excellence. A passion that never waned, and so touched the hearts of at least two generations of moviegoers.

On learning I was writing this book, a friend asked me why I chose to write on dead people. I replied that I seem to be so chosen. And take it on gladly because I could then try, through my writing, to make them come alive again.

Sathya Saran

April 2014

He missed being home. The green fields, the chatter of birds, the cries of men hawking their wares.

Here, the very music of life was stilled, and he could not bear the silence. Yet he had no option. This was the way of princes; to learn, to study and grow into fine men who could rule.

And though his father should have been a ruler, but was not; though he himself would possibly never be a king, he was yet a prince.

And so here he was, Sachin Dev Burman, reverentially called Sachin Karta, living among other princes, learning geography and history and math, but also learning somehow to be a prince.

He wondered if knowledge could be thus imparted or princely demeanour thus learned; the masters might know their subjects, but what could they possibly know of how to be a prince? And his mates were an unruly lot: used to getting their own way. Boisterous, pushy and loud, they intimidated the masters. He had little to say to them, or they to him. He was so different, lost in a different world.

At night, when the noise of the school day finally stilled and others slept, he lay awake, his ears straining to hear the music that lay hidden in his mind. The sound of his father expounding on a note, letting a raga unfurl. The flute as it was played in the field nearby, as the farmer sat against a tree, his days work done, the music soothing his tired limbs. Some nights he could swear he could hear Madhab chanting the singsong shlokas of the Ramayana under his breath as he worked, or singing them out loud in the evenings

In fact, the music never really went away. Yet one morning when it curled like smoke and played itself out even as the master pointed out hills and mountains on a map on the classroom wall, he put his head down on the desk to fight back the tears.

Next page