A LSO BY G EORGE B. S CHALLER

The Year of the Gorilla

Serengeti: A Kingdom of Predators

This is a Borzoi Book

Published By Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Copyright 1973 by George B. Schaller

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Schaller, George B.

Golden shadows, flying hooves.

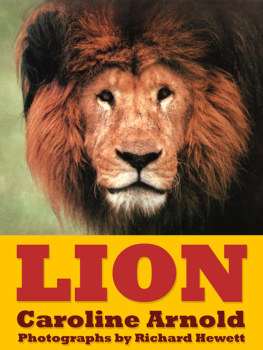

1. LionsBehavior. 2. Natural historyTanganyikaSerengeti Steppe. 3. MammalsTanganyikaSerengeti Steppe. 4. Serengeti National Park. I. Title.

QL737.C23S29 1973 599.74428 73-7280

eISBN: 978-0-307-82807-1

A portion of this book appeared in the June 1970 issue of Natural History Magazine. Natural History Magazine, June 1970.

v3.1

TO

Bernhard Grzimek

Acknowledgments

My study depended on the generous assistance of several institutions and many individuals. The National Science Foundation and New York Zoological Society provided the funds for the project, and the Institute for Research in Animal Behavior of the New York Zoological Society and Rockefeller University sponsored it. The National Geographic Society assisted with photography. The trustees of the Tanzania National Parks permitted me to do research in the Serengeti, where I received the cooperation of the Serengeti Research Institute. Many of the persons who helped me in East Africa are mentioned in the text, but I would like to extend my special gratitude to John Owen, former director of the Tanzania National Parks, who invited me to study lions, and to Myles Turner, Alan and Joan Root, Hans Kruuk, Stephen Makacha, Rdiger Sachs, Tony Sinclair, Howard and Dorothy Baldwin, Hugh Lamprey, William Holz, Hubert and Anneke Braun, and Charles Guggisberg for help in various ways. At my home institutions the late Fairfield Osborn, William Conway, Donald Griffin, and Peter Marler provided assistance. Richard Keane made the excellent lion sketches. Gordon Lowther was a stimulating field companion during our week of living the life of early hominids.

My wife, Kay, not only helped with the field work, spending many hours watching predators, but also schooled our sons, managed our home, and provided the stability and love without which the project would have lacked some of its essential ingredients.

The University of Chicago Press kindly permitted me to quote from and reproduce illustrative material from my scientific report The Serengeti Lion. Permission to excerpt some paragraphs from an article on the cheetah was granted by Natural History magazine.

Gordon Lowther and John Pfeiffer read and commented on the last chapter.

Assistance from the New York Zoological Society and a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation enabled me to spend time in writing this book.

Contents

Illustrations

M APS

Range of lion

Ecological features of Serengeti National Park 6

Serengeti National Park

S KETCHES

Aspects of play

Strutting and scent-marking postures of lions

Facial expressions of lions

The bared-teeth expression, in various situations

Walking and stalking postures of lions during a hunt

The Masai pride during its noonday rest.

A cub visits Brown Mane of the Masai pride.

A male and cub yawn in unison.

A lioness sits by her newborn cubs.

A playful cub bounds against its mother.

Masai pride lionesses with their cubs move out to hunt.

Crowded flank to flank, the Masai pride eats.

A lioness grabs the fleeing zebra with her forepaw.

A lioness pulls a zebra down.

Several lions squabble over a warthog.

Two male lions harass a bull buffalo.

A nomadic male rests on a kopje.

F OLLOWING

Wildlife concentrates near a waterhole in the Northern Extension.

A giraffe keeps a wary eye on a nearby lioness.

A reedbuck watches several lionesses.

Crowded around a waterhole, wildebeest are vulnerable.

A pack of hunting dogs scans the plains for prey.

Hunting dogs pursue a zebra herd.

A zebra foal has been overtaken and pulled to a halt.

Hunting dogs crowd around the kill.

Hunting dog pups play with a grass tuft.

A blackbacked jackal tries to chase vultures from the remains of a kill.

A hyena carries off a gazelle.

A stalking leopard.

A leopardess licks her large son.

George, playing an early hominid, captures a sick zebra foal.

Myles Turner directs the destruction of a poachers camp.

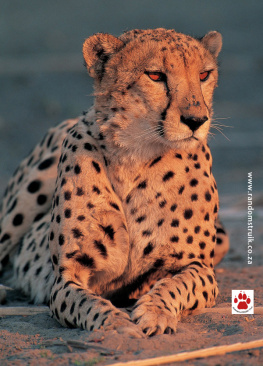

A cheetah female with her three cubs.

Cheetah family at rest.

A cheetah drags her gazelle kill.

A giraffe feeds in our front yard.

Blowing out the contents of an ostrich egg.

A picnic in the Moru Kopjes.

George feeds Giri, our pet warthog.

Fungus, our banded mongoose.

Eric and Rameses, our lion cub.

Mark wrestles with Rameses.

Introduction

The day after we arrived at Seronera, headquarters of the Serengeti National Park, I found two lionesses at the edge of the plains. They sat in the golden grass, their eyes fixed on a herd of Thomsons gazelle, their bodies straining toward the advancing animals as if willing them to come closer. As the herd continued its approach along a well-worn trail, oblivious to danger, the lionesses parted, one to the right, the other to the left. Their tawny bodies became but wisps of wind in the grass as they stalked into position to attack. Closer, closer came the gazelle until they were between the lionesses. Suddenly a breeze stirred, the gazelle scented the lions and scattered with wild leaps and twists, each racing blindly through the grass ignorant as to where the enemy lurked. One gazelle rushed toward a concealed lioness, and, spotting the motionless form too late, it leaped high in a desperate attempt to escape. But with exquisite timing the lioness reached up and with gleaming agate claws plucked the animal from the air. I took notes throughout the incidentthe size of the gazelle herd, wind direction, height of vegetation, the movement patterns of the lionesses, the age and sex of the victim and many of the other small facts that I hoped would ultimately contribute to an understanding of lion predation. The long, slow task of collecting information had begun.

When John Owen asked me to study the lions of the Serengeti, I was delighted to take on the task for several reasons. One was the lion itselfits beauty, its aura of barely contained power. Man feels an emotional kinship to these predators even though he is filled with primordial apprehension by their presence. When visiting a national park, he spends his time not with the giraffe, impala, or zebra but with the lion and leopard, vicariously exulting in the strength of these animals from the safety of a vehicle. This contagion probably reflects mans past as a hunter. Though a primate by inheritance, man has been a predator for several million years, and his whole outlook on life has been influenced by this. I knew that I would enjoy my months and years with the great cats, an important consideration, for even science may become tedious if the subject of the study does not provide both sensual pleasure and a touch of the mysterious.