Copyright 2020 by Ben Brooks

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Running Press Kids

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.runningpress.com/rpkids

@RP_Kids

Originally published in Great Britain in March 2019 by Quercus Editions Ltd, a Hachette UK company

First U.S. Edition: October 2020

Published by Running Press Kids, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Running Press Kids name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Illustrations by Quinton Winter.

Cover design by Arnauld.

Interior design by Sarah Green.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020934922

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-7215-4 (hardcover), 978-0-7624-7214-7 (ebook)

E3-20200825-JV-NF-ORI

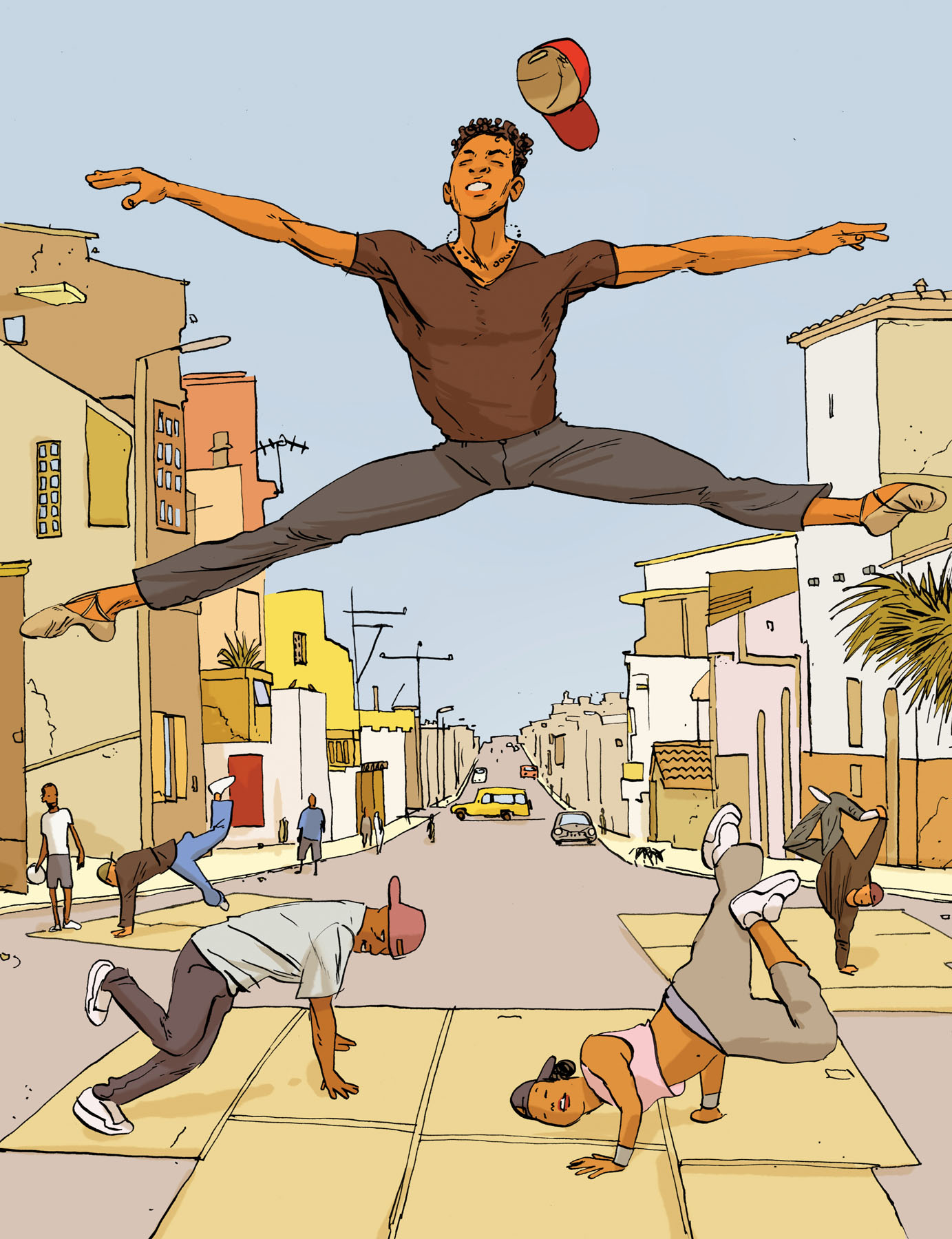

(BORN 1973)

Carlos grew up in a poor neighborhood in Cuba. He was kicked out of school when he was young, and his dad ended up in prison. Carlos was sent to the National Ballet School of Cuba simply because it was a place that could afford to feed him.

But his natural talent soon became apparent.

In 1990, Carlos won the Prix de Lausanne, a competition that pits hundreds of dancers from across the world against each other.

Carlos then traveled to Russia and became the first foreign person to become a guest artist for the Bolshoi Ballet. At twenty-five, he became the first black person to become a principal dancer at the Royal Ballet in the United Kingdom, as well as the first black person to play Romeo in a ballet.

Nobody who looks like me has ever played the roles I dance, said Carlos. When I first appeared in Swan Lake at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the auditorium was packed with black people.

He blew spectators away with his speed, precision, grace, and power. His otherworldly, flowing, electrified way of moving brought new life to many old ballets.

But ballet is famously tough on the body. Joints creak, feet bleed, and blisters form and burst. At forty-two, Carlos embarked on a farewell tour to mark his retirement from ballet. Five thousand people a night would turn up to cheer and cry as the dancer whod lit up their lives whirled across the stage for the final time. After his last performance, the audience hurled roses onto the stage and gave him a standing ovation that lasted an entire twenty minutes.

Carlos is now creating an academy in Cuba where people can study dance for free, hoping to nurture the beloved dancers of the future.

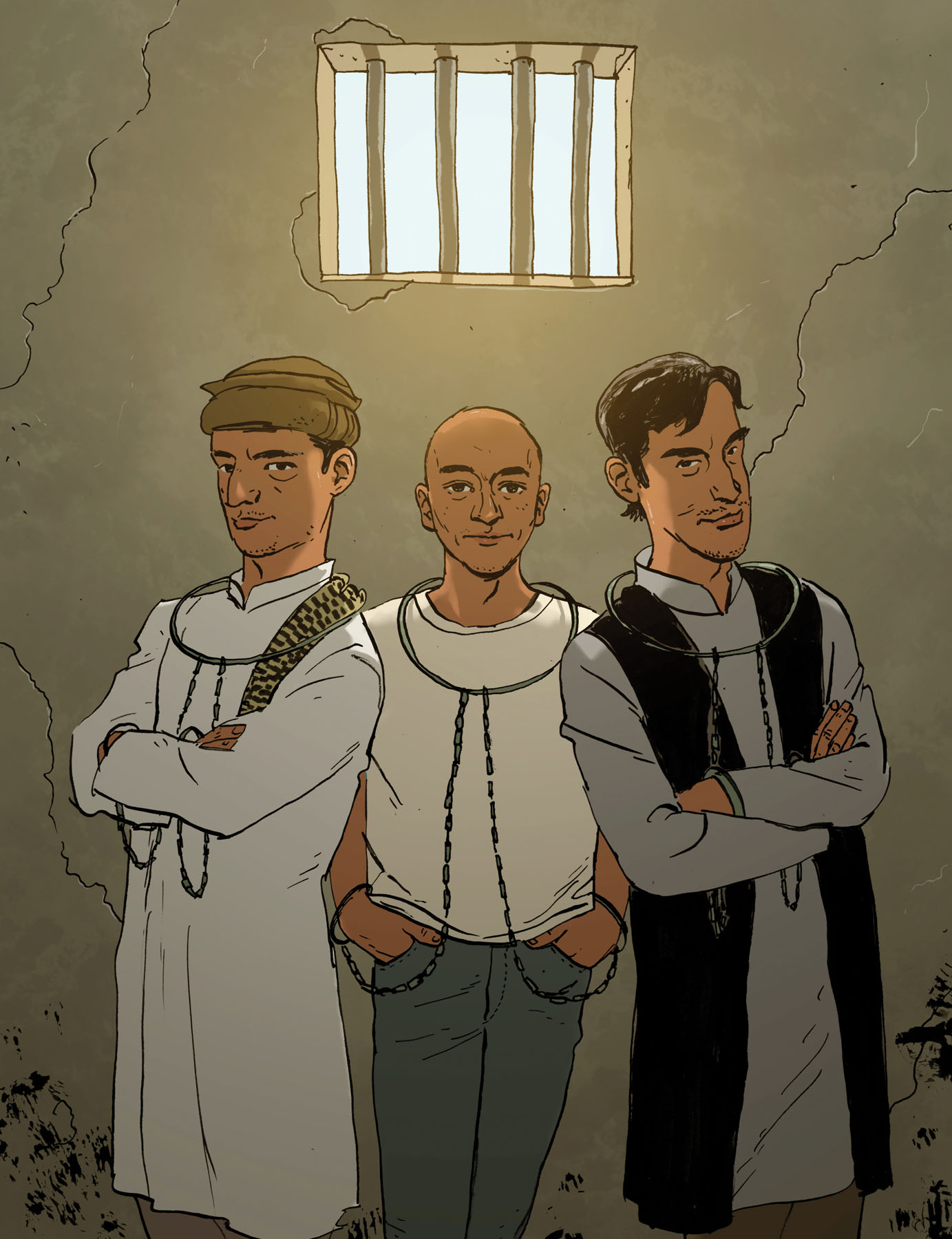

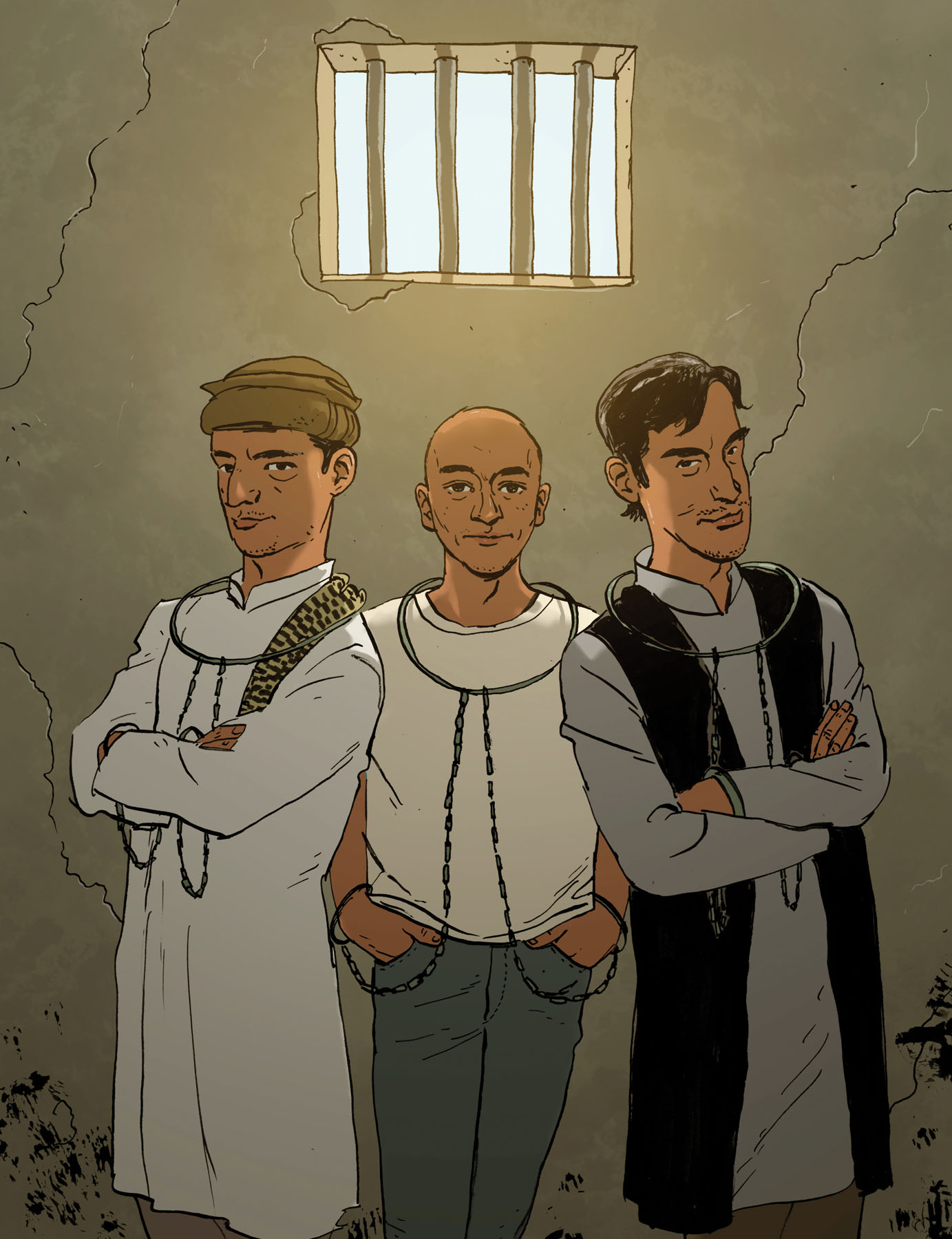

In 2002, a British reporter named Amardeep Bassey traveled to Afghanistan to chronicle the impact that the American invasion was having on its people. It was a dangerous place and, for safety, he hired two local guides, Noushad and Khittabshah.

Both Noushad and Khittabshah belonged to Pashtun tribes who dwell in the Khyber Pass, a dangerous, mountainous route that is the main connection between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Together they helped Amardeep successfully cross from Pakistan to Afghanistan. In the capital city of Kabul, the reporter interviewed ordinary people about how the war had affected their daily lives. Then he headed back into Pakistan with Noushad and Khittabshah.

They were stopped at the border. Amardeep was told he didnt have the correct visa to pass through.

You two may go, the border guard told the Pashtun tribesmen. But we are taking him.

The guards were convinced that Amardeep was an Indian spy. They hauled him off to jail, where he was locked in a small cell filled with robbers, murderers, and terrorists. Coming from the West meant he would have very likely been a huge target for violence inside the prison. However, he was not alone. Noushad and Khittabshah had volunteered to be arrested alongside him. They were not going to abandon a man theyd promised to protect.

Without them, I would have crumbled, said Amardeep.

The two men looked after him for twenty-eight days. When Amardeep was finally released, they were made to stay inside the jail until hed left Pakistan.

The three of them kept in touch. Some years later, Amardeep returned to Pakistan to thank the men who went through prison to help a stranger from a distant land.

(BORN 1988)

Ibrahim grew up with thirteen siblings in Deir ez-Zor in Syria. They would spend their days playing basketball, practicing Judo, and swimming in the blue waters of the Euphrates River. Then civil war broke out.

One day, Ibrahim was in the street when rockets crashed down around him. He threw himself into the nearest building for cover. That was when he started hearing cries for help. His friend had been hurt and was lying in the open.

Sprinting out to help him, Ibrahim was struck by a rocket.

He managed to haul himself to safety, but the damage to his leg was irreparable. It had to be amputated. Medical services and supplies were so limited that Ibrahim woke up twice during the harrowing operation and was sent home the next day without any pain relief.

Seeking better medical care, Ibrahim traveled to Turkey and made the dangerous crossing to Greece on a rubber dingy. He was granted asylum and settled in Athens. Initially, Ibrahim used a wheelchair for transport but was eventually fitted for a prosthetic leg. He used it as a chance to get back into swimming.

Two years later, Ibrahim competed in the Paralympics in Brazil, as part of the Independent Paralympic Athletes Team, a group made of refugees and asylum seekers. He was also chosen by Greece to carry their Olympic torch. Proudly, Ibrahim raised the lit beacon as he walked through a refugee camp in the center of Athens.

I am carrying the flame for myself, Ibrahim said. But also for Syrians, for refugees everywhere.

There are now an estimated sixty-five million displaced people around the world. Ibrahim hopes he can act as proof they can rebuild their lives.