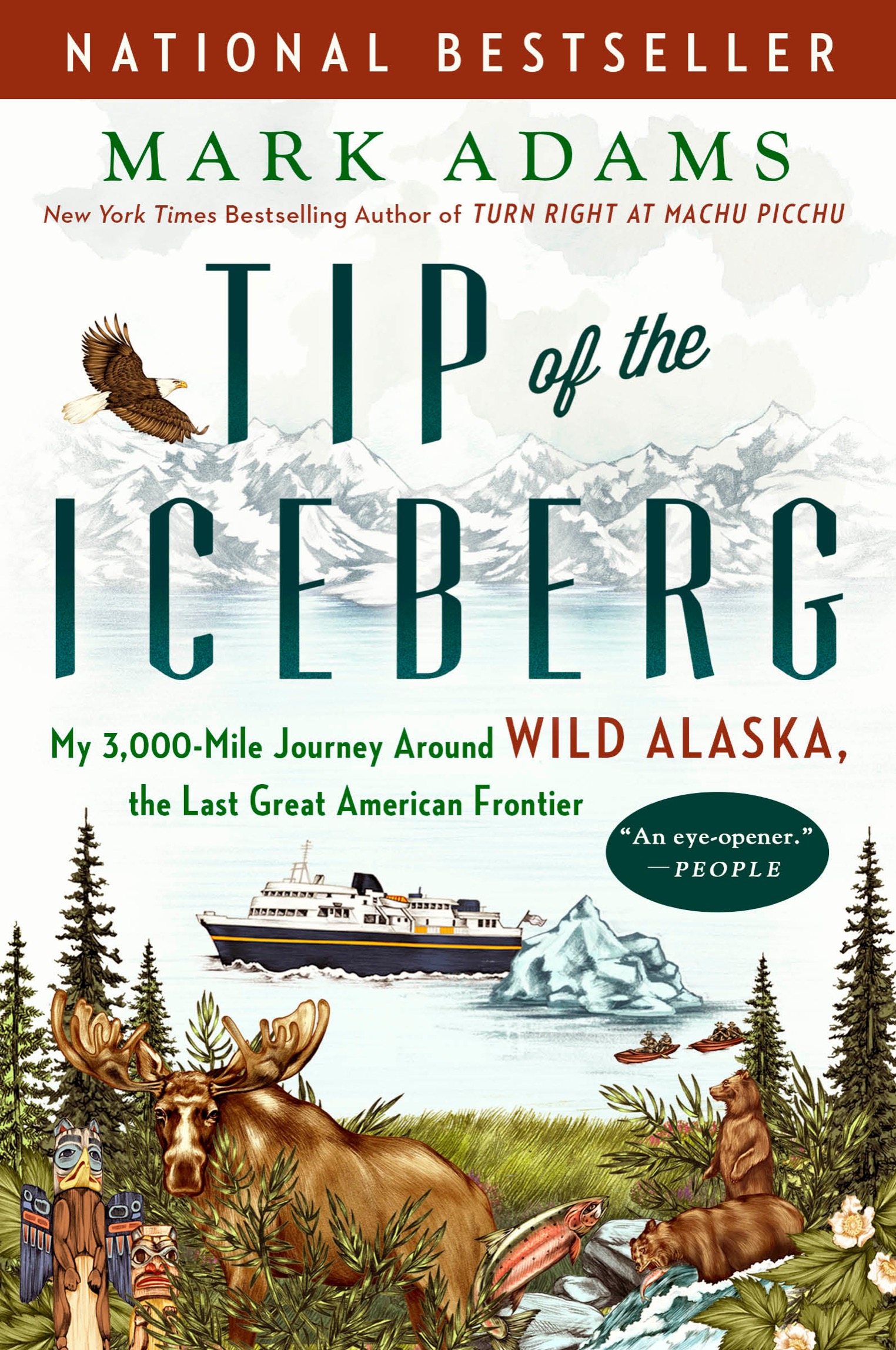

ALSO BY MARK ADAMS

Mr. America: How Muscular Millionaire Bernarr Macfadden Transformed the Nation Through Sex, Salad, and the Ultimate Starvation Diet

Turn Right at Machu Picchu: Rediscovering the Lost City One Step at a Time

Meet Me in Atlantis: Across Three Continents in Search of the 2,500-Year-Old Sunken City

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2018 by Mark C. Adams

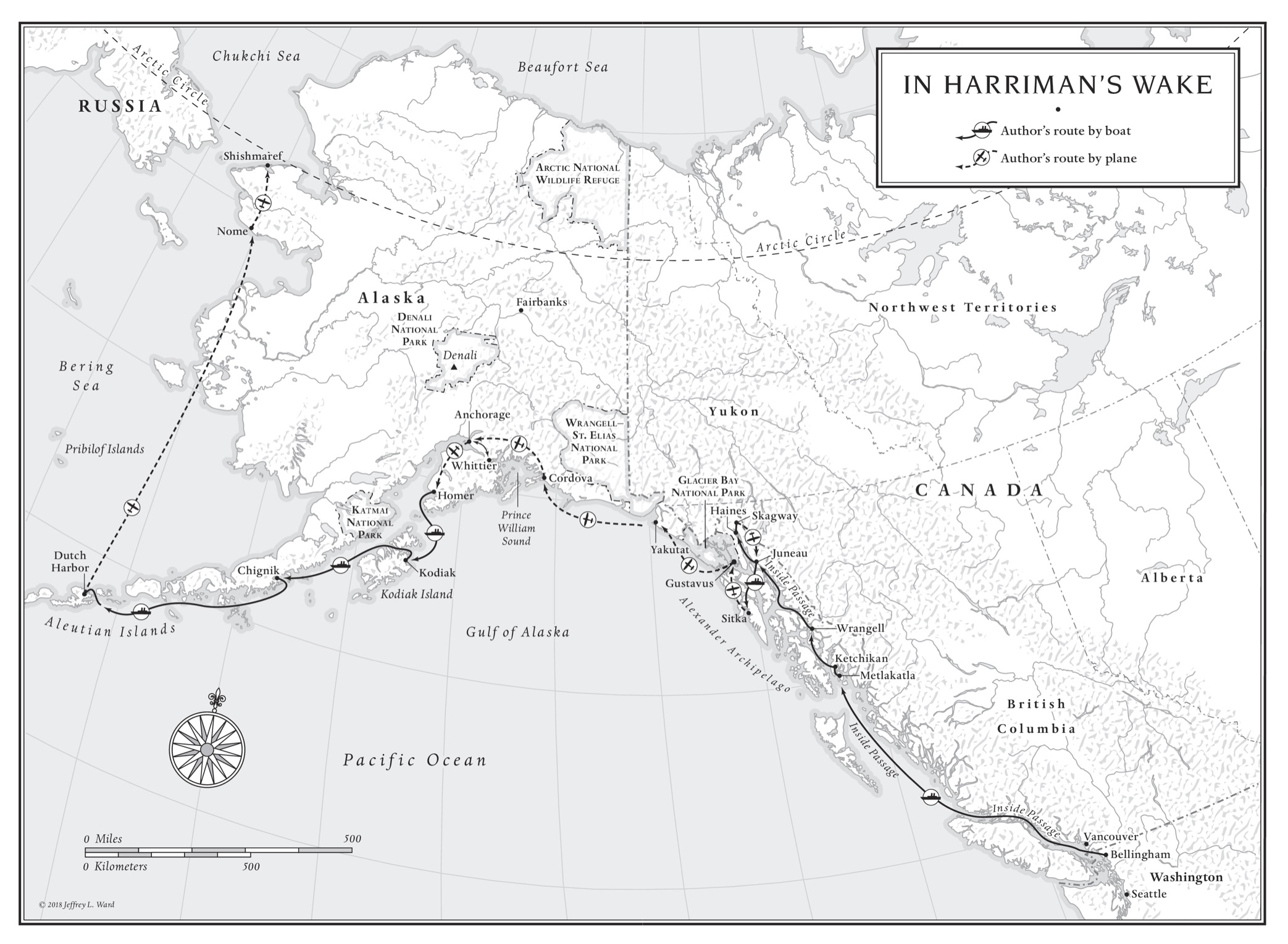

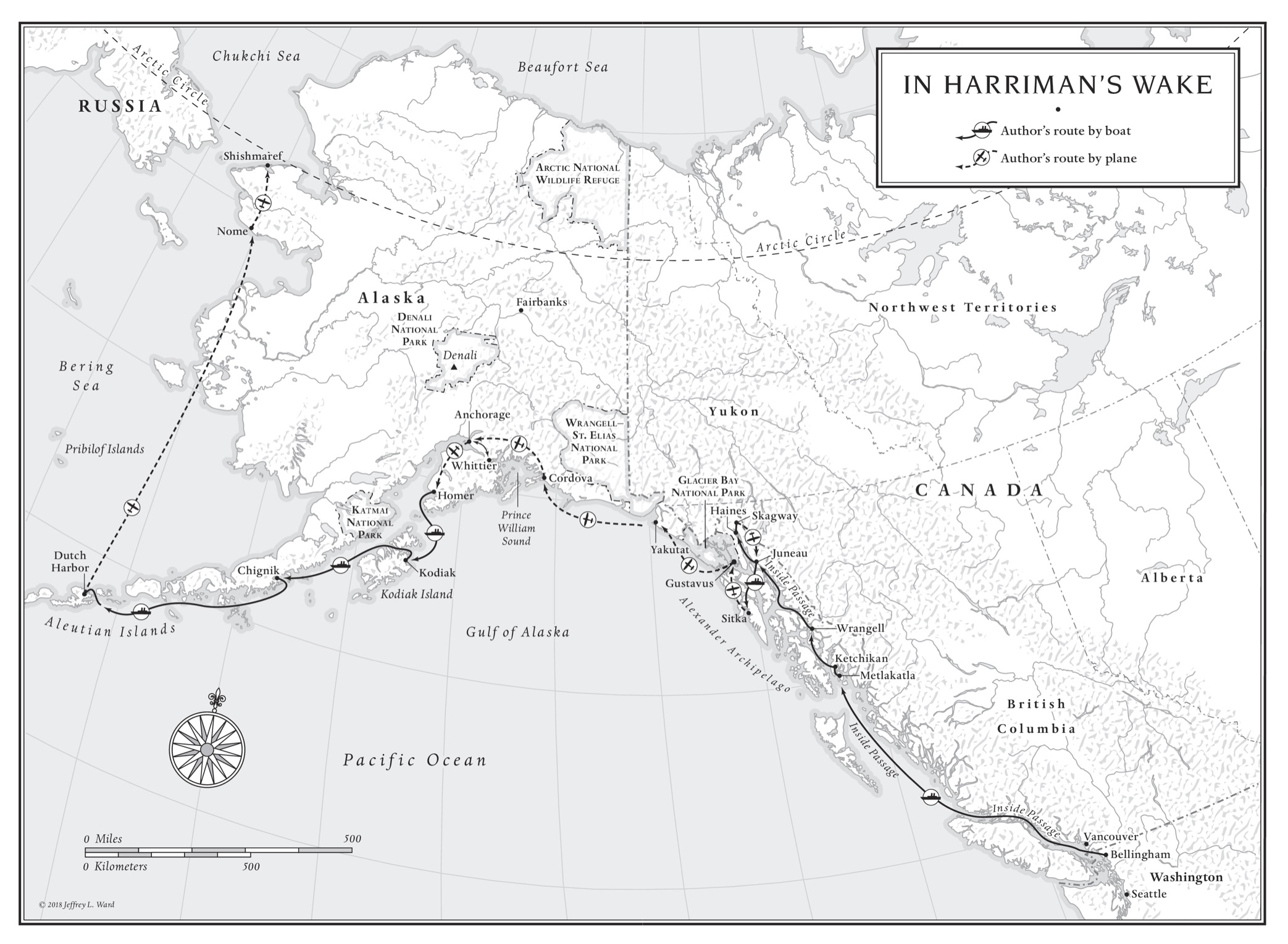

Maps by Jeffrey L. Ward

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTON and the D colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING - IN - PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Adams, Mark, 1967 author.

Title: Tip of the iceberg : my 3,000-mile journey around wild Alaska, the last great American frontier / Mark Adams.

Other titles: My three thousand-mile journey around wild Alaska, the last great American frontier

Description: New York, New York : Dutton, An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, [2017]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017039007 (print) | LCCN 2018003370 (ebook) | ISBN 9781101985113 (ebook) | ISBN 9781101985106 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: AlaskaDescription and travel. | Adams, MarkJourneys.

Classification: LCC F910.5 (ebook) | LCC F910.5 A313 2017 (print) | DDC 917.9804dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017039007

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_2

For Lauren, Kerry, Jason, and Sarahtravel companions from way back

I told him he must reform, for a man who neither believed in God nor glaciers must be very bad, indeed the worst of all unbelievers.

John Muir, Travels in Alaska

Authors Note

The figure of three thousand miles in this books subtitle was calculated on paper with a pencil and ruler, and includes water, air, and ground travel. In other words, it could be off by a little, or by a lot. My 3,286.4 Mile Journey Around Wild Alaska, Roughly Half of Which Occurred on the Sea and Should Therefore Probably Be Tallied as Nautical Miles might be more accurate, but it wouldnt fit on this books spine. Any young Scouts working on cartography badges may notice that if you count all the sea miles from Bellingham, Washington, to Dutch Harbor, Alaska, that number is also, coincidentally, about three thousand.

Also, a few minor identifying details in this story, including some names, have been changed because not everyone Ive written about knew they were going to be characters in a book.

Prologue

GLACIER BAY NATIONAL PARK

Our two-person kayak skimmed the surface of Glacier Bays glassy water, the bow pointed like a compass needle at the rocky lump of Russell Island. The sun was out, always a pleasant surprise in Southeast Alaska, and a light mist lingered around the islands upper half. Wed been paddling for about an hour, but I had no idea how far wed come or how far we had left to go. My sense of scale hadnt yet acclimated to the vastness wed enteredwater, sky, and mountains were all I had to work with. Aside from the splash of our paddles and the occasional tap-tapping of sea otters cracking open mussels, all was quiet.

Will there be anyone else on Russell Island? I asked David Cannamore, who was seated behind me. David was a former college athlete who guided kayakers around Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve all day, every day during the summer. He paddled with the metronomic grace of a professional tennis player volleying against a ball machine and accounted for perhaps 80 percent of our forward progress.

I seriously doubt it, David said. Ive camped a lot of places in this park, but never on Russell Island. There probably arent even any bears there.

Bears were just one subject Id never given much thought to back in New York City that seemed to come up again and again in Alaska. Others included the five varieties of Pacific salmon, the structural integrity of permafrost, recipes for moose meat, the declining quality of rubber boots, and a simmering resentment toward Washington, DC, that fell under the general rubric of federal overreach. Glaciers were another popular topic. As David and I paddled across the silent immensity of Glacier Bay, we were surrounded on all sides by the parks namesake rivers of ice flowing down from the mountains. Their frozen innards glowed a phosphorescent blue that eclipsed the cloudless sky above. A few times every hour, the giants discharged ice from their wrinkled facescrack, rumble, splashone of natures most spellbinding performances.

According to the slightly damp map I kept pulling out of a pocket beneath my life vest, the glaciers of Glacier Bay were doing something else, too. They were melting, and had been doing so for some time. There was no better evidence of this than Russell Island. In 1879, the then unknown conservationist John Muir had first scouted the bay in a dugout canoe guided by Tlingit Indians. Russell Island marked the furthest reach of his journey, for it was embedded in two hundred feet of solid ice, a pebble crushed beneath the leading edge of a glacier that flowed back up beyond the horizon into Canada. For the next twenty years, Muir returned repeatedly to Glacier Bay and its ever-changing landscape. On his seventh and final visit, in 1899, Muir estimated that the ice wall had retreated four miles. Russell Island was surrounded by open water.

Wavy lines on my map, each labeled with a year, demarcated the former extent of Glacier Bays namesake ice in decades past. These were the shrinking borders of an empire under siege, evidence that in the century following John Muirs visits, the frozen kingdom whose praises hed sung had been dissolving like a popsicle in the sun. Muir Glacier, named to honor the writer who literally put Glacier Bay on the map and almost singlehandedly created the market for scenic Alaska cruises, had withdrawn more than twenty miles since 1879.

For many people, especially environmentalists who revere John Muir as a nature prophet, this glacial retreat is obvious evidence of global warming. Which makes sense until you stop to ask why the ice had begun melting before the gasoline-powered automobile was invented. In some places along Alaskas coast, including Glacier Bay, one can find glaciers that are