Table of Contents

Also by Bill Porter/Red Pine

In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu

The Platform Sutra

The Heart Sutra

Poems of the Masters

The Diamond Sutra

The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain

The Clouds Should Know Me by Now

The Zen Works of Stonehouse

Lao-tzus Taoteching

Guide to Capturing a Plum Blossom

Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits

The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma

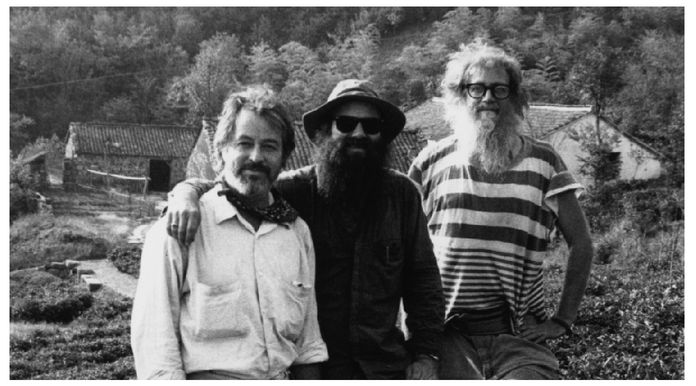

For my fellow pilgrims Finn Wilcox and Steve Johnson

So the 20th Centuryso

whizzed the Limitedroared by and left

three men, still hungry on the tracks, ploddingly

watching the tail lights wizen and converge slipping

gimleted and neatly out of sight.

from The River by Hart Crane (1899-1932)

NO WORD

I finally returned home, just as the long twilight of a Northwest summer was beginning. A few hours earlier, I had been sitting in a plane flying so low over the town where I live I could see the stand of doug fir next to my house. I wondered how high the grass had grown. I had been away ten weeks. The plane banked, and the town disappeared. Thirty minutes later, we landed in Seattle. A taxi to the Coleman Docks, a ferry across Puget Sound, and two buses later, my friend Finn Wilcox picked me up next to the Port Townsend Safeway and drove me to my side of that five-acre stand of trees someone donated to the town as a bird sanctuary.

It was the Buddhas birthday, the eighth day of the fourth lunar month, which fell on May 5 that year. Buddhists mark the day by pouring water over small statues of a standing, infant Shakyamuni. I celebrated in the clawfoot tub upstairs and thought about the journey that just ended. Afterwards, I tried to sleep. But I was still in China. So I got up and began writing this book, which begins in Beijing.

I arrived the night of February 26. It was spring. In China spring begins on New Years Day, which was January 29 in 2006. So it had been spring for nearly a month. But the ancient Chinese who decided when spring beganon the first day of the new moon closest to the midpoint between the winter solstice and the spring equinox lived along the Yellow River, three hundred miles to the south. In Beijing, it was still winter. While I was standing in the airport taxi line, I opened my pack and got out my parka. It was just a shell, and what I really needed were my long johns, but putting them on in public was not an option.

Normally I would have headed for a hotel. But my friend Ted Burger had offered a roommates bedroom. His apartment was a sixth-floor walk-up at the top of a dark stairwell in a dark building in a dark compound in the eastern part of the city. The taxi driver found the right street and the right compound, but there were a dozen buildings in the compound and no outside lights. I couldnt see the numbers, and it took me three tries before I found the right building and the right stairwell.

Ted wasnt there. He was at a film festival in America showing his documentary on Chinese hermits, Amongst White Clouds, but his American roommate was home and let me in. The apartment was small and furnished as the young furnish their apartments everywhere, as if no one was planning to stay very long and money would be better spent on something more useful, like a bottle of wine. But the place was heated, and there was a radiator in every room. It was so warm I had to leave the window open in my bedroom that night. The bedroom belonged to Teds Chinese roommate, who had offered to stay with her parents while I was there. There wasnt much in the room besides the bed, a bedside table, and a chest of drawers. But I was glad to begin my trip in something other than a hotel, and the accommodations seemed just right.

I was making a pilgrimage to places associated with the beginning of Zen in China, specifically its first six patriarchs: Bodhidharma, Hui-ko, Seng-tsan, Tao-hsin, Hung-jen, and Hui-neng. These were the men who put Zen on the map, and I wanted to pay my respects. None of the six ever made it to Beijing, but there were some underlying issues I wanted to consider before I met the old masters. The first of those issues was language. And Beijing seemed like a good place to begin.

Zen was known for its cavalier, if not dismissive, attitude toward words. To talk about it is to go right by it, those old Zenmen were fond of saying. And yet no school of Buddhism has generated as much literature. Thousands of books have been written, in the East as well as in the West, about what cannot be expressed by language. I didnt expect to find an answer to this conundrum, but I wanted to circle around from behind and maybe catch it unawares. So when I woke up the next morning, I called my friend Ming-yao. Ming-yao was the editor of the Buddhist magazine Chan, which was how the Mainland Chinese romanized the word Zen.

Whenever I say Zen, people are always correcting me: Its Chan/Chan (the Wade-Giles and Pin-yin romanizations of the word). They say, Zen is the Japanese form of Chan. Chinese Chan is different from Japanese Zen. Thats one way of looking at Zen, as a cultural phenomenon. But Chinese Chan, Japanese Zen, and Korean Son all point to the same moon of the mind. And there arent two kinds of mind.

The reason I like to point with Zen, as opposed to Chan, is that I love a good Z. Also, zen was how people pronounced this word back when Zen began (the reconstruction preferred by linguists is dzian). And the people who live in the Kan River watershed of Kiangsi Province, where zen became Zen, still pronounce it that way. The pronunciation used at court changed when the Manchus invaded China in the seventeenth century and established the Ching dynasty and their own pronunciation as the arbiter of proper usage. But down in Zenland, its still Zen. Besides, Zen isnt Chinese or Japanese anymore. It belongs to anyone willing to see their nature and become a buddha, anyone who lives the life of no-mind and laughs in these outrageous times.

So I called up Ming-yao, and he asked me to meet him for lunch. He said his wife Ming-chieh would be there too. Ming-chieh translated my book on Chinese hermits, Road to Heavenexcept, of course, for the parts about politics, the military, and the police, which never made the Chinese edition. Everyone liked her title: Kungku-yu-lan: Hidden Orchids of Deserted Valleys. Strange as it sounds, no one had ever written a book about hermits in China, and the publication of Kungkuyulan had a noticeable impact. In the Sian area, it even resulted in the formation of a hermit association, which sounds ludicrous. But the association has since compiled a record of hut and cave locations in the Chungnan Mountains south of Sian where I conducted my interviews. And it now sends someone around periodically with medicine and foodand even mail.