To Lisa Diamond and Tim Duke

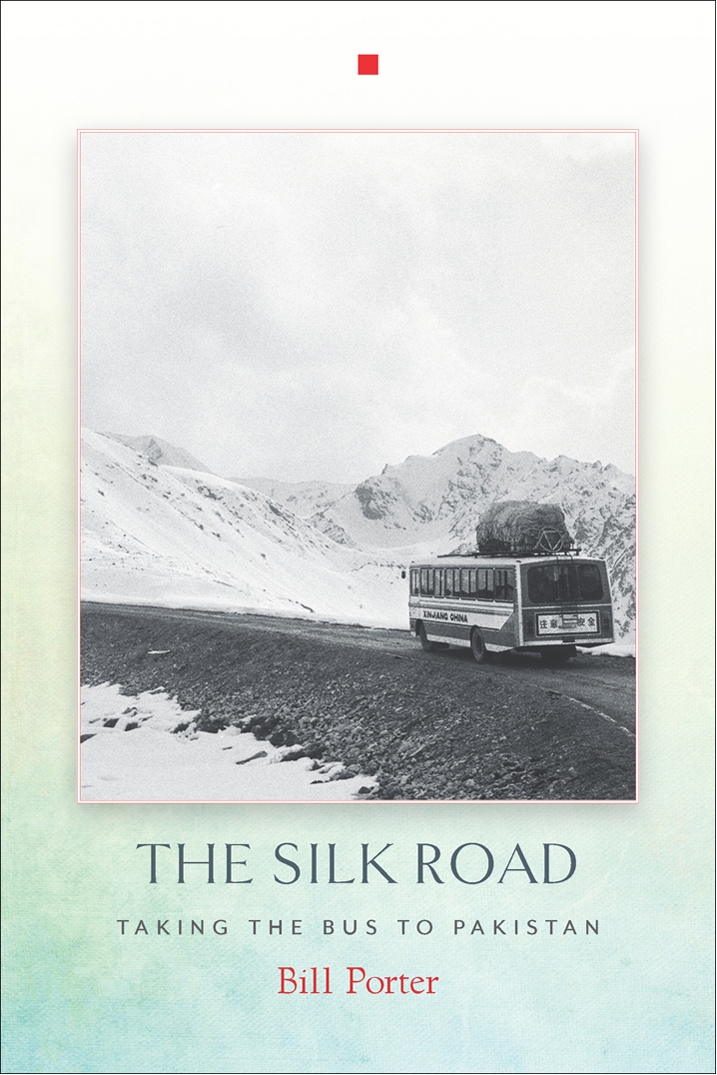

Text and photos copyright 2016 by Bill Porter

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Cover and interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

Typesetting by Tabitha Lahr

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

e-book ISBN 978-1-61902-751-0

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

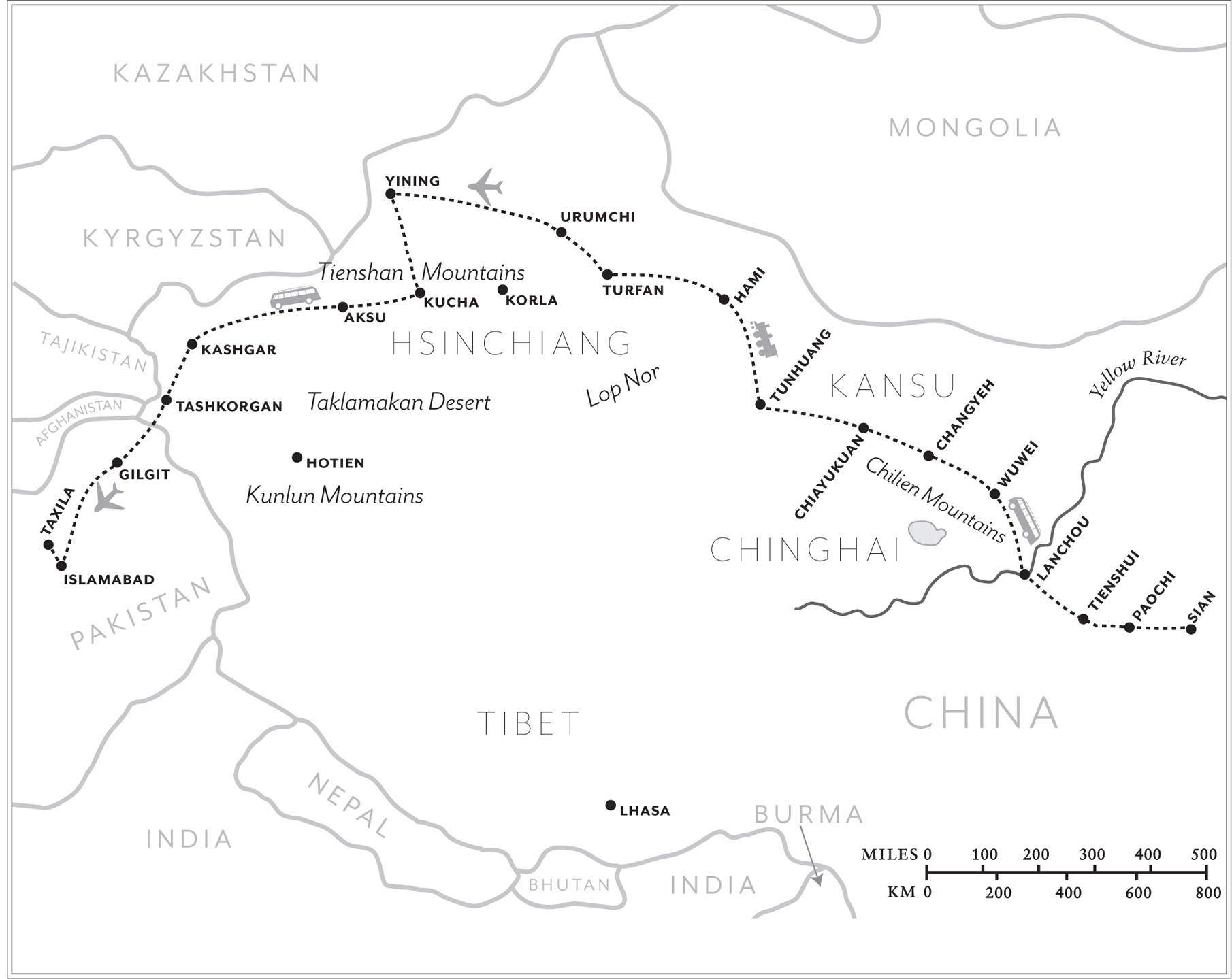

E VER SINCE WE HUMANS FIRST BEGAN to walk, we have worn paths to our neighbors house and to the next village and beyond. And ever since we discovered the wheel and learned to tame four-footed beasts, some of our trails have become roads. Among the more monumental examples are the hewn rock ramparts of ancient Romes Appian Way and the poured concrete cloverleafs of the LA freeways. A much older, much longer, and at the same time less tangible example of our peripatetic nature is the Silk Road.

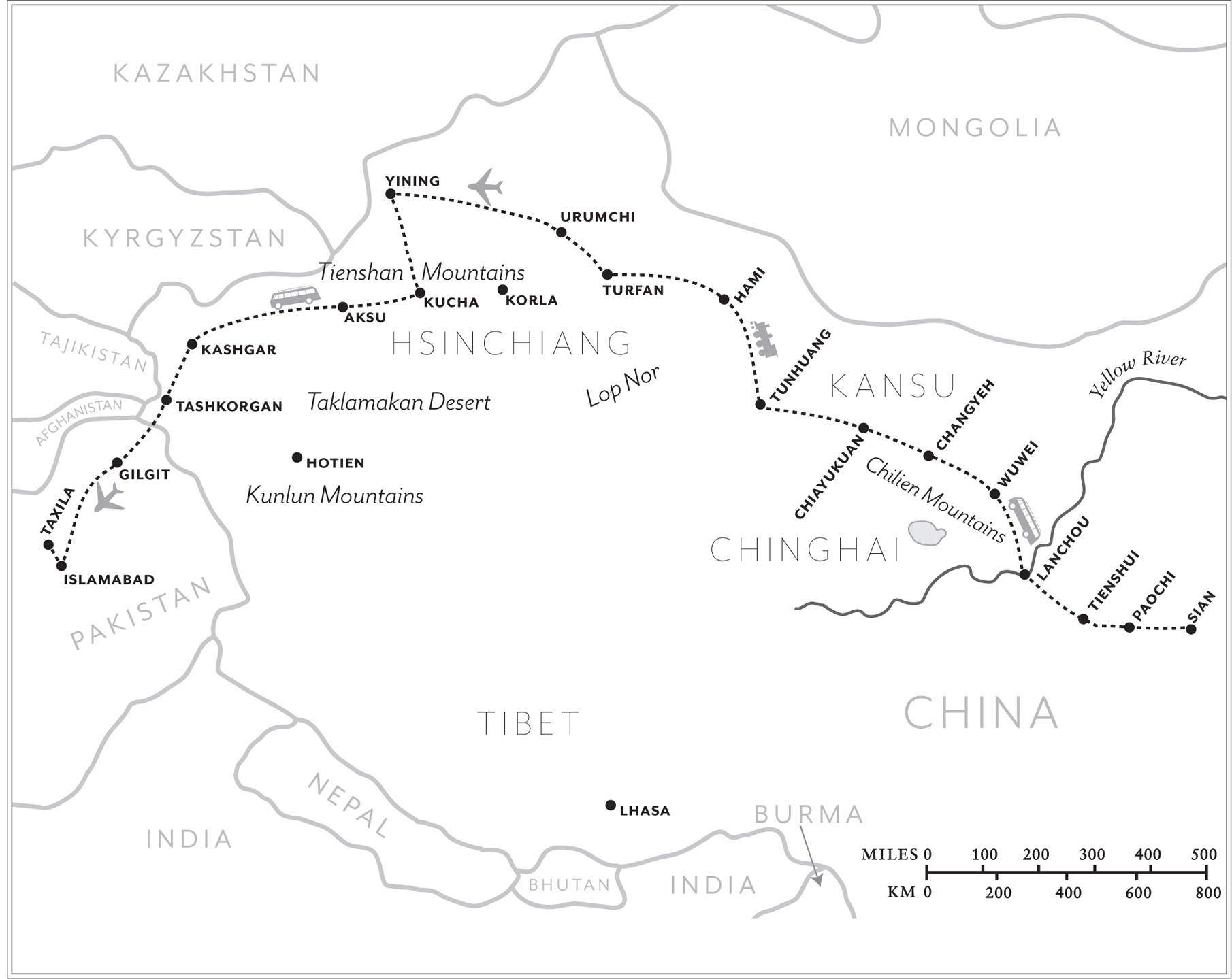

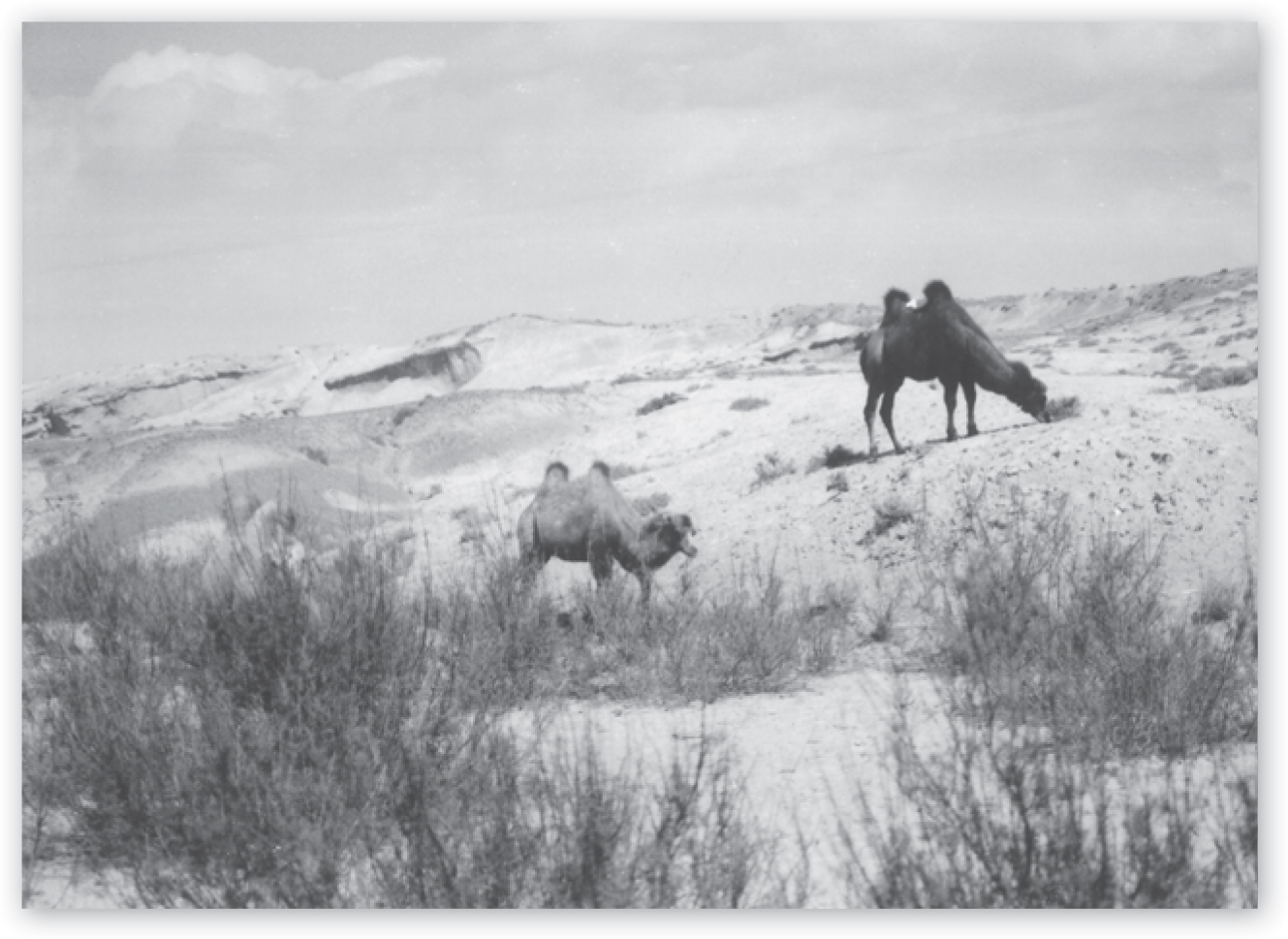

During its heyday, this will-o-the-wisp highway carried bolts of silk from the Yangtze delta towns of Suchou and Hangchou across all of Asia to the shores of the Mediterranean, where it was exchanged for its weight in gold. But silk was only one of the roads important commodities. The Chinese spent just as much on incense and precious stones coming the other way. The road also brought many of the items still associated with China: musical instruments and forms of dance and art and religionthings we think of as integral to Chinese culture. For their part, the Chinese never called it the Silk Road. That honor goes to the nineteenth-century German scholar Baron Ferdinand von Richthofenthe uncle of Snoopys nemesis, Manfred von Richthofen. The Chinese knew it only as the Road to the West. And traveling it was one of the most dangerous missions a person could undertake. It was a road through swirling sand and searing heat, past demons and apparitions, into lands that only the demented, exiled, or simply foolhardy dared venture. I wasnt sure to which category I belonged, but in the fall of 1992 I decided to travel this road, from China all the way to Pakistan. Because it was going to be a long and an arduous trip, I decided not to travel alone. I asked my friend Finn Wilcox to join me. Finn made his living planting trees and doing yard work. Fall was the beginning of his slack season, and so he signed on.

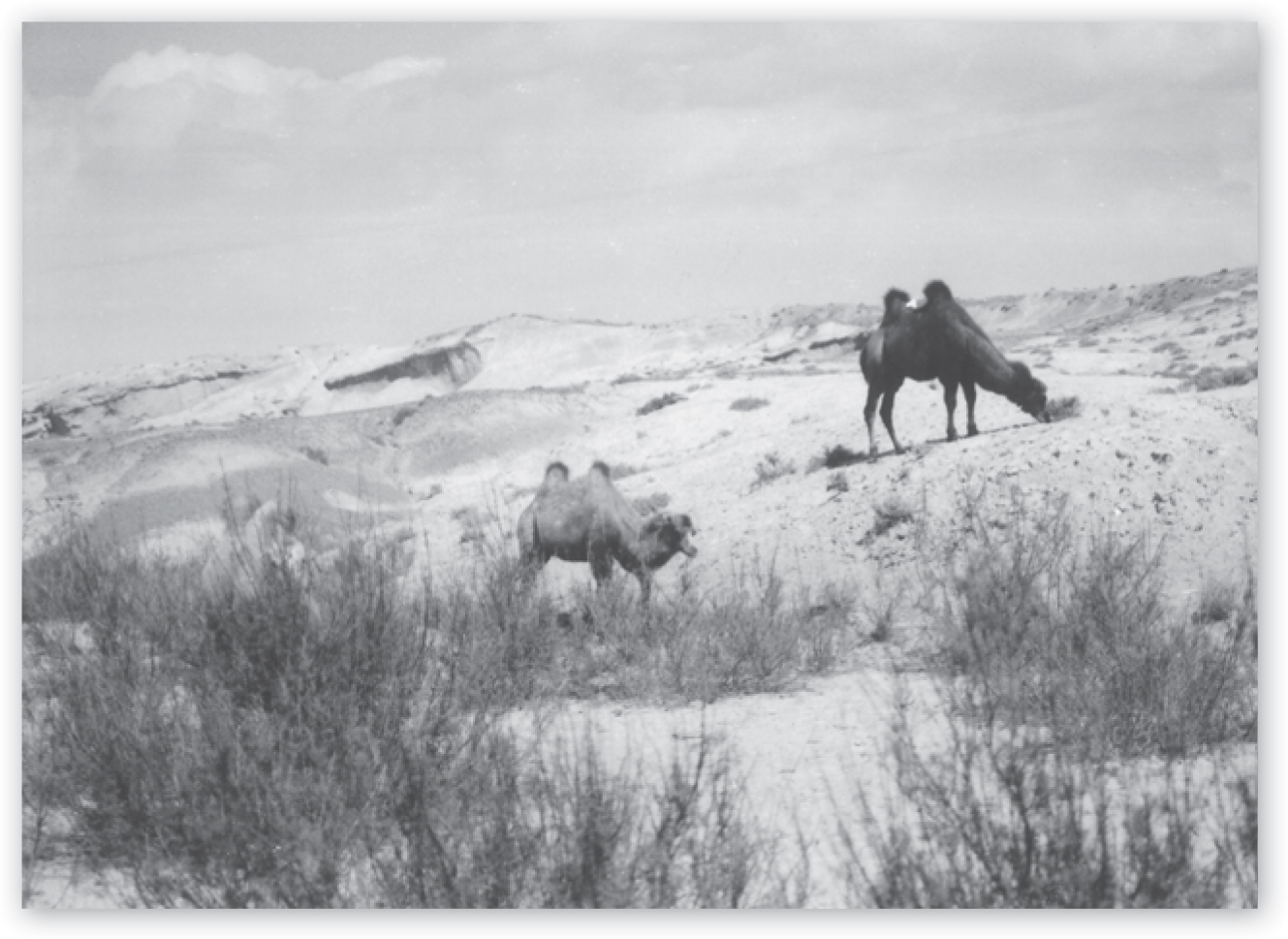

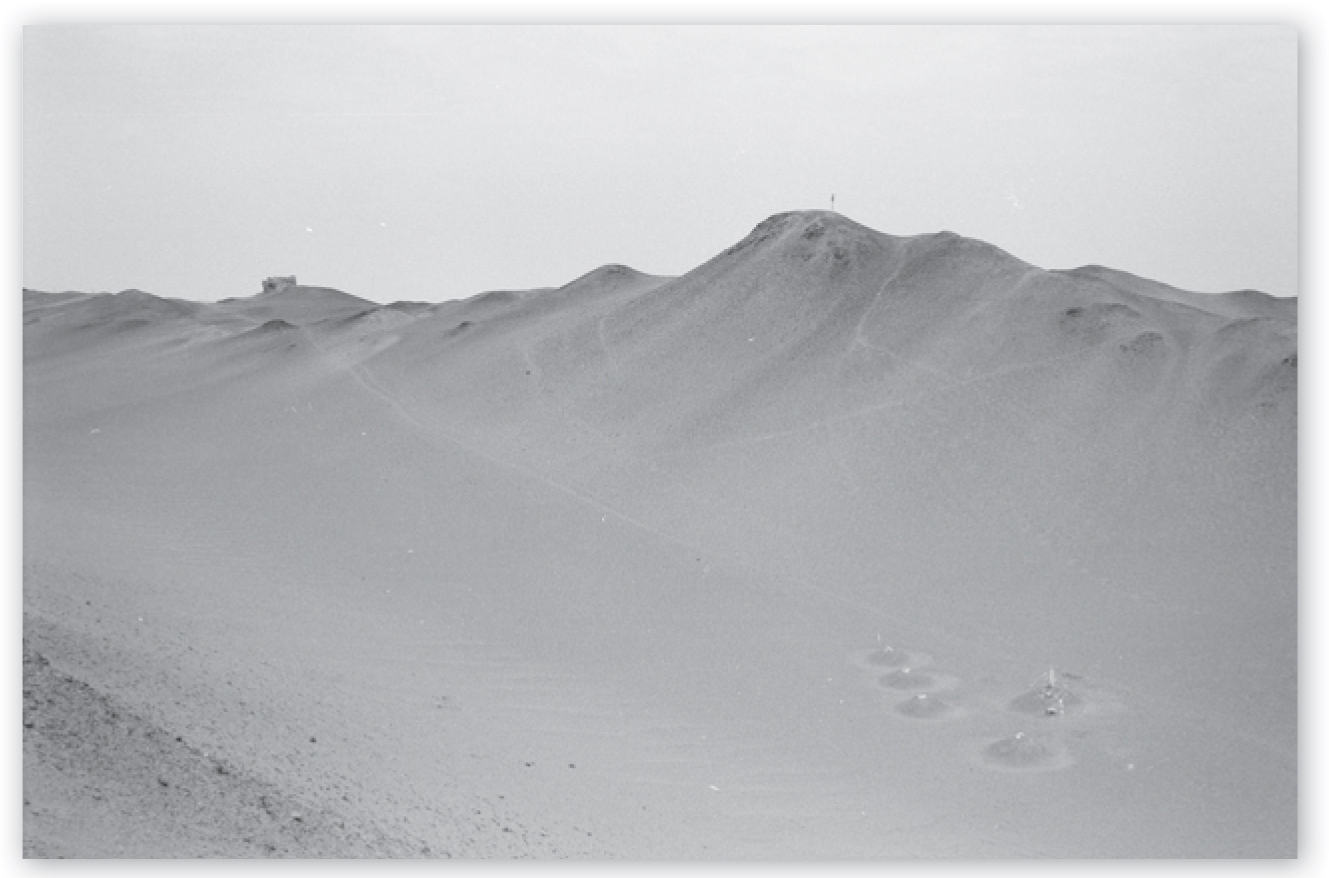

The Silk Road wasnt what a person would normally think of as a road. Until recently, there was no actual road, simply a trail of bones and animal dung left by the most recent caravan. A passing dust storm, and the road was gone, until the next caravan found its way across one of the worlds more barren landscapes to the next oasis.

Exactly when or how this trade route developed, or who was responsible for its creation, remains a matter for archaeologists to work out. The migratory routes of nomads who lived in the grasslands of Central Asia crisscrossed this region, and certain groups stayed behind to settle low-lying pastures and oases. And when some found it more profitable to carry goods between these oases than herd their flocks, they provided the string that linked these islands of green together. But it wasnt until the time of Julius Caesar that this string turned to silk.

As I began to get ready, I considered what to take. Since I wasnt joining an organized tour that took care of baggage and transport problems, a suitcase was out of the question. And since I wasnt planning any sorties into the wilderness, so was a backpack. The problem with a backpack was that if the frame didnt break when someone threw something heavy on it, it got in the way trying to squeeze onto a bus or trying to work ones way down a train corridor. What I needed was a rucksack, in other words, a pack with shoulder straps but without a frame. And I just happened to have one. It was my old Forest Service rucksack. It repelled water and pickpockets, up to a point, and while it was only half as big as most backpacks, it held all that I needed.

First, I needed something to keep the whiskey in. Bottles were out of the question, and metal flasks weighed too much. I opted for a pint-size plastic bottle, one whose top screwed on securely. I couldnt afford to waste a drop. The Silk Road was littered with the bones of those who couldnt make it to the next oasis. Once I had the pack and the whiskey out of the way, the rest was easy: a couple changes of clothes, long johns in case it turned cold, a cashmere vest for stepping out at night, and a lightweight jacket, a wool hat and gloves, just to make sure. And I never forget pictures of friends and family and earplugs and a flashlight and spare batteries and toilet paper. That was all I needed, that and a thermos. Finns pack was pretty much the same.

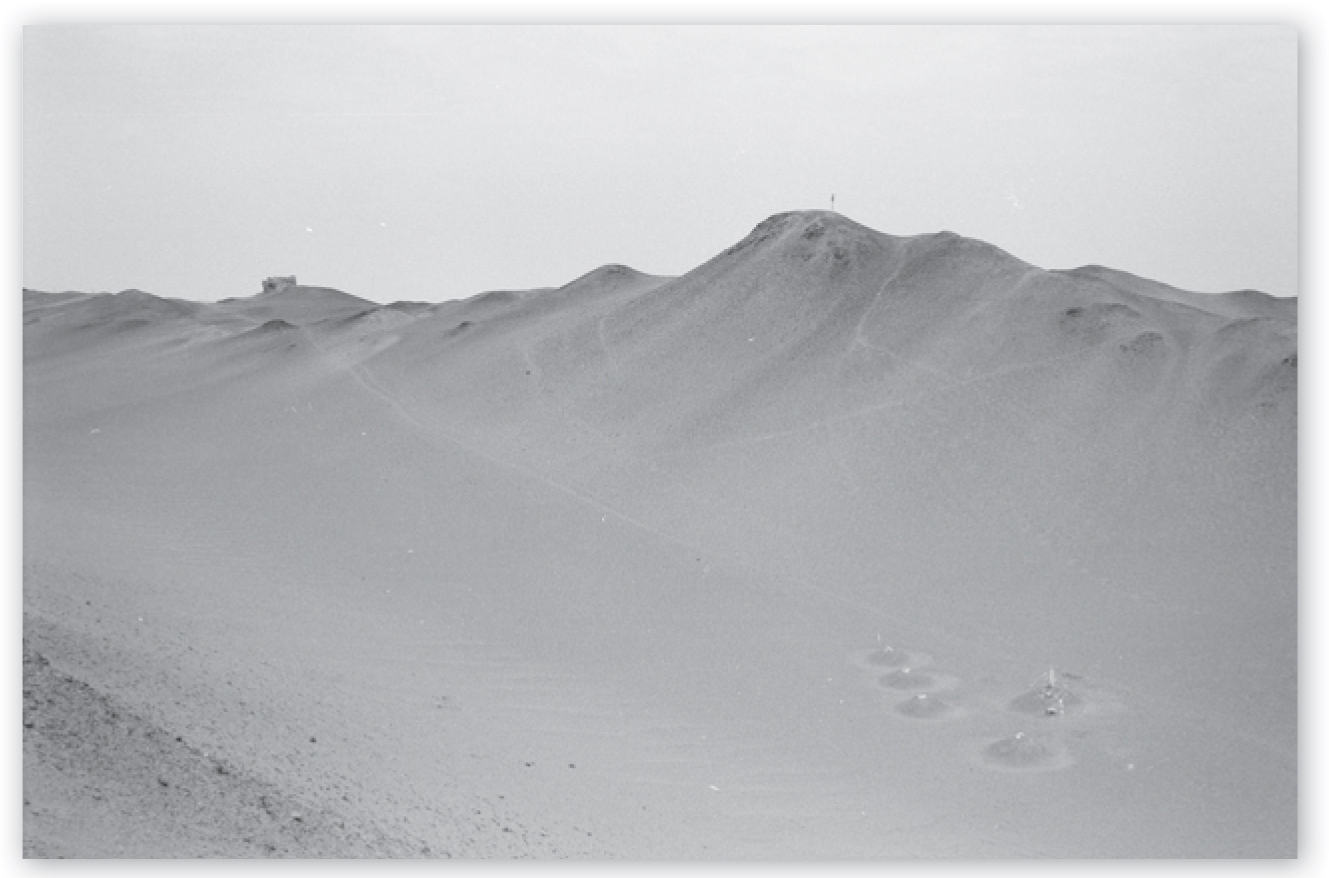

Travelers graves beyond Yangkuan Pass

Once we were packed, it was time to begin our big adventure. But where to begin? Since my plan was to travel westward as far as Pakistan, the most natural place to begin was at the Silk Roads eastern terminus in China. But it turns out that during the many dynasties that ruled China over the past few thousand years, the capital, and thus the eastern end of the Silk Road, varied. Sometimes it was in Loyang, and sometimes it was in Kaifeng. Sometimes it was even in Beijing. Usually, though, the road ended at the gates of Chang-an, or Sian, as its now known. So that was where we headed.

Since we were entering China from Hong Kong, we could have taken the weekly direct flight from the Crown Colony. But there was also a daily flight from Kuangchou, and flights from Kuangchou, being domestic flights, were 50 percent cheaper. So we headed for Kuangchou. Unfortunately, the day we began our trip was August 29, which turned out to be the beginning of Hong Kongs four-day Liberation Day weekend, which celebrated Hong Kongs liberation from Japanese occupation during World War II. Train tickets to Kuangchou had been sold out for weeks, so we had no choice but to take the subway to Lo Wu and walk across the border to Shenchen. Easier said than done. Despite getting an early start, by the time we arrived at Lo Wu, half of Hong Kong was in line. There we were just starting out, and already we were beginning the weight-loss program that was part of every trip to China. The temperature was in the nineties. We felt the ounces rolling off as we shuffled slowly forward toward the oldest bureaucracy in the worldwhich China introduced to the West, you guessed it, via the Silk Road. Still, it was a bureaucracy that worked, and we finally made it through immigration and customs. But when we came out the other side, we found ourselves part of a mob. There were at least 10,000 people milling in front of the Shenchen train station. Like us, they were all trying to get to Kuangchou.