INTRODUCTION

The Silk Road was arguably the most important thoroughfare in human history. Wars were waged over it and desperate diplomacy employed to keep it open. Trod by countless merchants and missionaries, envoys and bandits, emperors, kings, princesses and peasants, it brought both prosperity and disaster, providing a conduit for the trade in luxury goods, the movement of marauding armies and the transmission of devastating diseases. But perhaps most importantly, it was also an artery for ideas, a driving force in the exchange of culture and technology across Eurasia; primarily running eastwest between China and the Middle East, its impact extended even further afield.

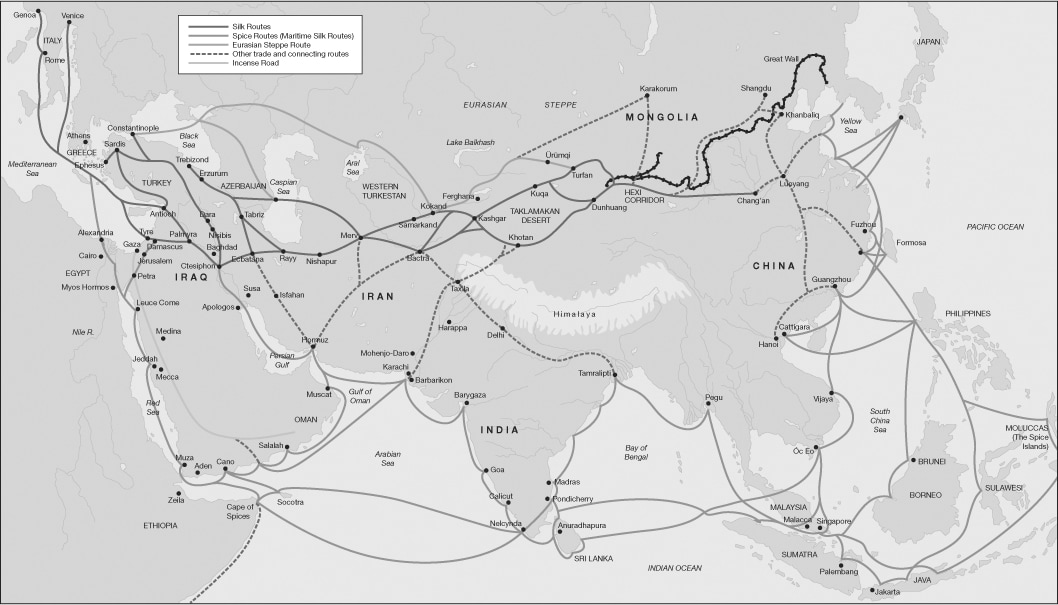

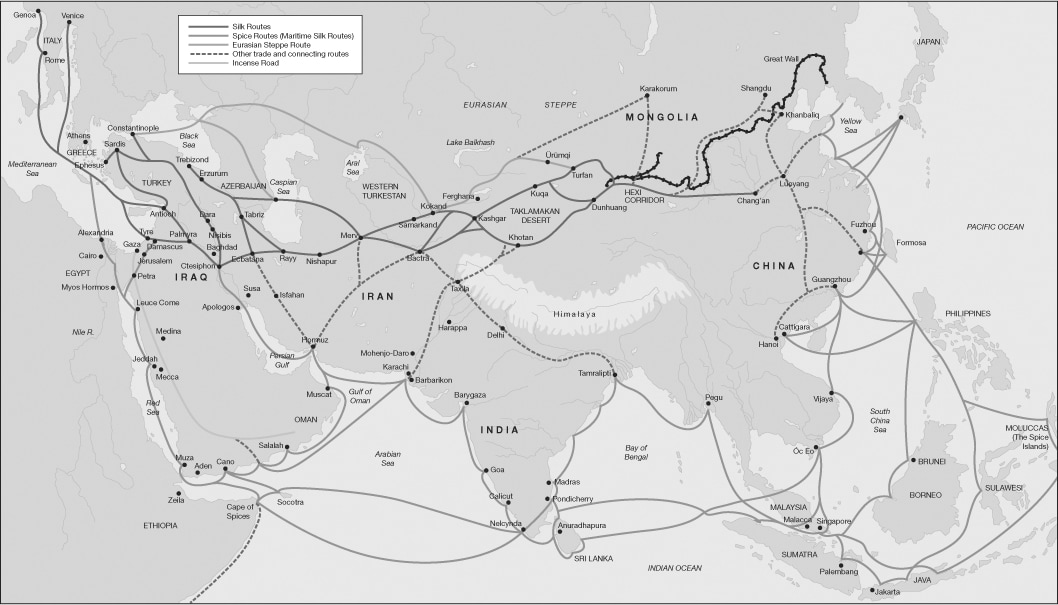

Only coined during the late 19th century, the term Silk Road is a misnomer in more ways than one. First, it wasnt a single road but an ever-changing network of routes, often barely discernible tracks through inhospitable regions hardly deserving of the name road. Second, although the Roman Empires desire for Chinese silk provided much of the early impetus for trade along the network, the routes carried much more, from spices, incense and gems to horses, porcelain and weapons. And finally, the overland routes were connected to, and eventually replaced by, a maritime Silk Road that linked ports around the margins of the Indian Ocean and through to the Mediterranean.

In telling the story of the Silk Road, the focus is sometimes on its heartland in Central Asia and Chinese Turkestan the area around the Taklamakan Desert and Pamir Mountains. In other contexts, it becomes relevant to encompass a much broader swathe across Eurasia from the shores of the Mediterranean to the East China Sea, and to look in more detail at the Middle East and central China, even India or Siberia. This book reflects that fluidity, shifting its gaze according to the aspect under consideration.

A map showing the various routes of the old Silk Roads on land and by sea.

The Silk Roads existence is a consequence of both humanitys propensity for mercantilism and the geography of Central Asia, with its formidable mix of mountains and deserts, which constrained the options available for eastwest trade. Millennia in the making, the highway entered its golden age towards the end of the first millennium CE during Chinas Tang dynasty, but eventually faded from memory as traders turned to less arduous routes and the desert sands obscured and then obliterated the ancient camel tracks.

Since they were rediscovered during the 19th century, the legendary trade routes of the overland Silk Road have captured the popular imagination, conjuring up images of parched deserts, fertile valleys and treacherous mountain passes, isolated oasis settlements and imperial cities, vast camel caravans, nomad armies and lone pilgrims. And with the opening up of Central Asia following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Silk Road tourism is on the cusp of a boom.

In the 21st century, as the world becomes increasingly interconnected, the Silk Roads have taken on a new lease of life. Their heritage value has been acknowledged by the United Nations, new rail links have already been established, and China is embarking on an ambitious (and costly) plan to reopen multiple strands of the ancient routes the beginning of a new chapter in one of historys greatest stories.

1

ORIGINS OF THE SILK ROAD

T he vast territory through which the various branches of the Silk Road and its predecessors ran includes a wide diversity of habitats, from forbidding deserts and extensive grasslands to high mountain ranges and their foothills. Chill northern forests give way to semi-arid steppe, which in turn morphs into the deserts of Central Asia: the Taklamakan, the Gobi, the Karakum, the Kyzylkum.

PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY

Mountain ranges dissect the region: the Altai, the Pamirs, the Tian Shan, the Karakoram, the Kunlun. Rising to elevations of up to 4,000 m (13,000 ft), these formidable peaks create what were, in the early part of their human history, a series of essentially self-contained areas. Far from any ocean and its moist winds, they receive scant rainfall: standing water is generally scarce, although there are some lakes, rivers and small spring-fed oases. The lack of water for agriculture constrained settlement, as only rivers flowing from the mountains provided predictable supplies.

This combination of forbidding mountain ranges, harsh deserts and a general lack of resources, in particular water, limited the options not only for the formation of settlements in Central Asia but also for routes connecting those settlements. Diversity of landscapes and climates meant that cultural development across the continent was diverse too, in both its speed and pathways. Thus physical geography shaped the Silk Roads.

The geography of the Silk Road encompassed massive mountain ranges such as the Altai in western Siberia and northwest Mongolia.

HUMAN GEOGRAPHY

Modern humans probably began to move into Eurasia about 40,000 years ago. These early hunter-gatherers were then slowly replaced from around 9000BCE as migrants arrived from the Middle East, bringing with them knowledge of primitive farming.

However, the northern steppe regions proved inhospitable to farmers. The climatic conditions low, unpredictable rainfall and high evaporation rates and infertility of the soils, combined with the low levels of agricultural technology at the time, made farming difficult, if not impossible. Yet the steppe has one thing in abundance: grass. And not just any old grass, but highly nutritious grass. Thus it provided perfect conditions for the development of livestock herding. Over time, the geographical differences between the northern and southern regions meant the northern areas were mostly populated by nomadic herders, while in the south lived settled farmers, although it was by no means a clear-cut distinction.

TIMELINE

C. 4500 BCE | Beginning of the Copper Age |

C. 3500 BCE | Domestication of the horse and the Bactrian camel; horse-based pastoralism in the Eurasian steppe |

C. 3300 BCE | Beginning of the Bronze Age |

C. 3000 BCE | Wheeled transport develops |

C. 2000 BCE | Steppe Route and Nephrite and Lazurite roads in operation |

C. 1800 BCE | Settlements begin to form in the south; nomadic pastoralism develops in the north |

C. 1300 BCE | Development of horse-based warfare |

C. 1046 BCE | Start of Zhou dynasty |

C. 1000 BCE | Nomadism spreads across the steppe; horse-basedwarfare becomes more common |

C. 900 BCE | Nomads begin to attack settled farming communities |

C.600 BCE | Horseback riding spreads across the steppe |

Next page