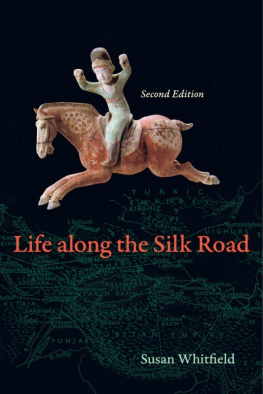

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

My original intention in writing this book was to exploit the manuscripts and other sourcestextual and materialdiscovered at Dunhuang and other sites in Chinese Central Asia to attempt to provide an accessible and reliable introduction to the complex history of this region in a widerSilk Roadcontext. The original book was published under a U.K. trade imprint, John Murray, and therefore was not in a format that allowed notes. I am pleased now to have the opportunity to include them. Where possible, I have included references to primary sourcestextual, visual, and materialand also to translations of the textual sources. This accords with my attempts to make the study of the Silk Road accessible to more people. For this reason I have also added links to online versions of translations and articles where available and to illustrations of the manuscripts and artifacts excavated from the Silk Road sites. Many of them are also freely available online through the International Dunhuang Project (IDP; online at http://idp.bl.uk).

Following the publication of the first edition, I started work on an exhibition at the British Library using much of the research and showing many of the objects used for the book (Whitfield and Sims-Williams 2004). I followed this with another exhibition in Brussels showing new finds from the Silk Road in China (Whitfield 2010), and both projects expanded my understanding of the material culture of the first millennium AD. In additions to new excavations and finds, new textual sources have emerged, and I have therefore been able to supplement the text and revise some of my interpretations. I am also delighted that many more secondary historical sources now exist to help students, and I have cited these where relevant and hence reduced some of the historical background that I felt was necessary in the first edition. However, this field is still comparatively sparse. For example, there is as yet no historical monograph in English on any of the Tarim kingdoms, though there are now sufficient sources to write one.

Thanks to the new finds and publications and the research of other scholars, my own knowledge has increased, though I am always aware of how many yawning chasms remain. I have also traveled more widely in this area, visiting many more of the major and remote archaeological sites in the Taklamakan desert and other sites in Central Asia. I have retraced the steps of the Chinese and Tibetan solders fighting from the Amu Darya, now in Afghanistan, to the ancient kingdom in the Yasin valley, now in Pakistan, told in The Soldiers Tale, and some of the route over the Lowari pass into the Chitral region, told in The Pilgrims Tale. This has given me a more acute awareness of the challenges of travel in this region and a great respect for these early travelers of the Silk Road.

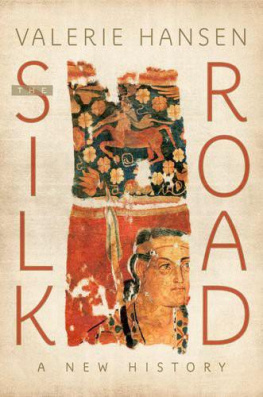

In the first edition, I limited the geographical region to eastern Central Asia into China, including the Mongolian steppes and Tibetan plateau. I also concentrated on the Tarim basin and Dunhuang because of my knowledge of and access to the wealth of primary and material sources for that region. I decided not to set a story in the ancient kingdom of of Turfan, despite the rich sources, as everyday life there had been covered well in English by others, notably Valerie Hansen (1995, 2013). I also limited the timescale to the last quarter of the first millennium AD. This was partially dictated by the primary sources and by my own knowledge, but it also allowed the chapters to overlap and offer the same events from different perspectives in order to deepen understanding of this complex period and the many peoples and cultures that populated it. The book was intended to be a slice of Silk Road history, to give the reader a taste for the whole and thus a hunger to discover more. The original story took place as the Silk Road was changing: the decline of cultures such as the Sogdians, who had played a key role in early trade, the rise of new powers on the steppes, and the introduction of Islam and the subsequent decline of Buddhism and the other religions of the area.

For this revised edition, I added a chapter (within the original timescale but extended geographically) and a prologue (set some two centuries previously). These new chapters are intended to incorporate the steppe and sea routes and to bring Africa and Europe into the story while retaining the core focus on Central Asia and the Tarim. I decided not to extend the timescale beyond the tenth century despite the temptation of a number of rich primary sources. There are now excellent studies on the Chinese maritime routes and Indian Ocean trade of this period and later, during the Mongol period, with the unification of much of Eurasia under a single power. A brief survey with references is given in the epilogue for those who wish to explore further.

My new prologue, The Shipmasters Tale, takes us to the early sixth century and introduces two aspects of the Silk Road that have often been neglected (though this is changing): the involvement of African merchants, and the interdependence of the land and maritime routes. It also introduces Christianity and Judaism. Although I have had an interest in the Axumite kingdom for many years and have visited several of the sites, it is not my area of specialism, and I have thus relied more heavily here on secondary sources and the comments of kind colleaguesbut, of course, any errors and omissions are my own. In addition, only limited information is available on maritime travel, and I have therefore not been able to add many details to that section. Fortunately, the field of maritime archaeology is developing and bringing up many more finds from the seabed, so it is expected we might learn much more over the coming years.