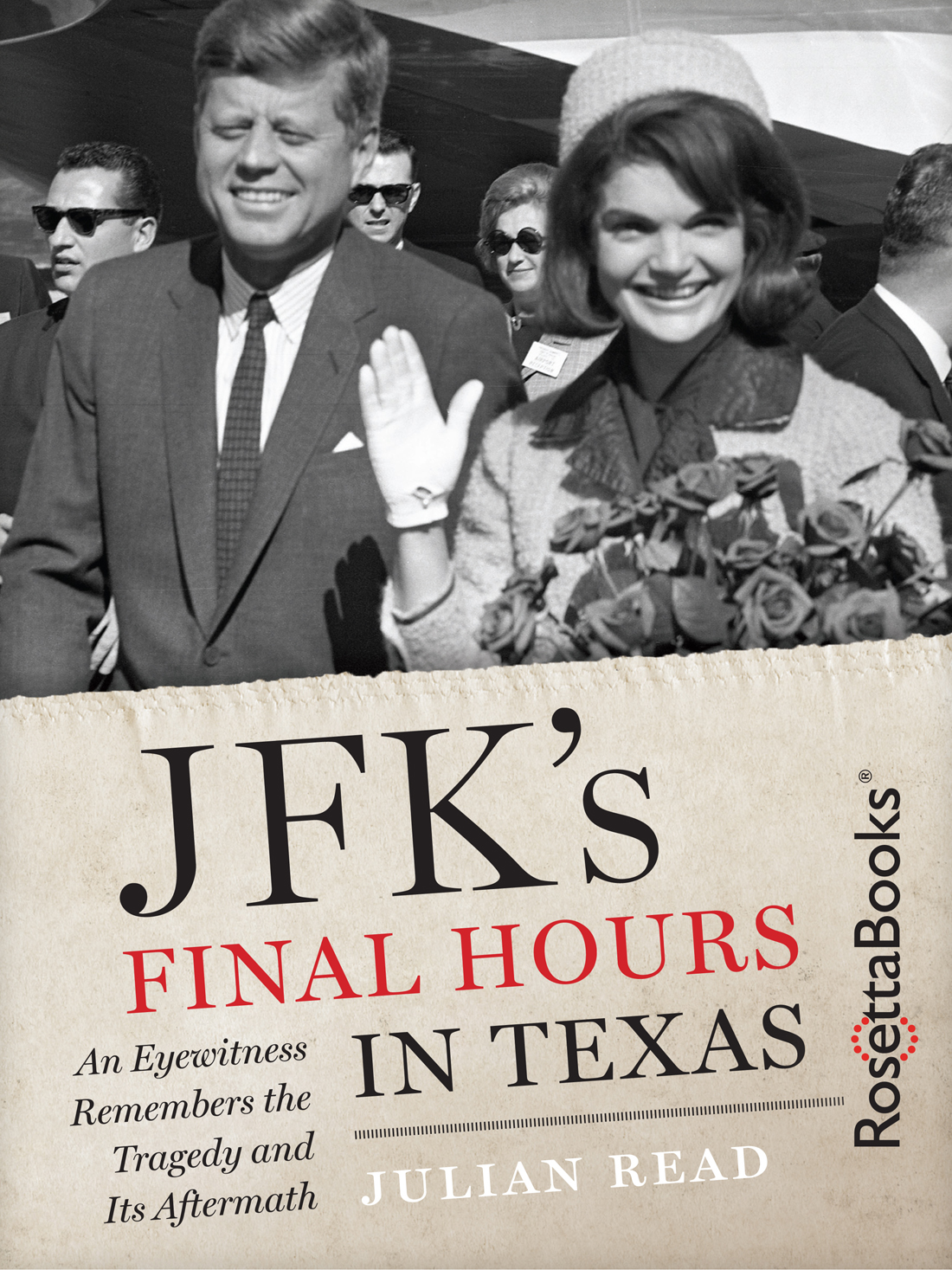

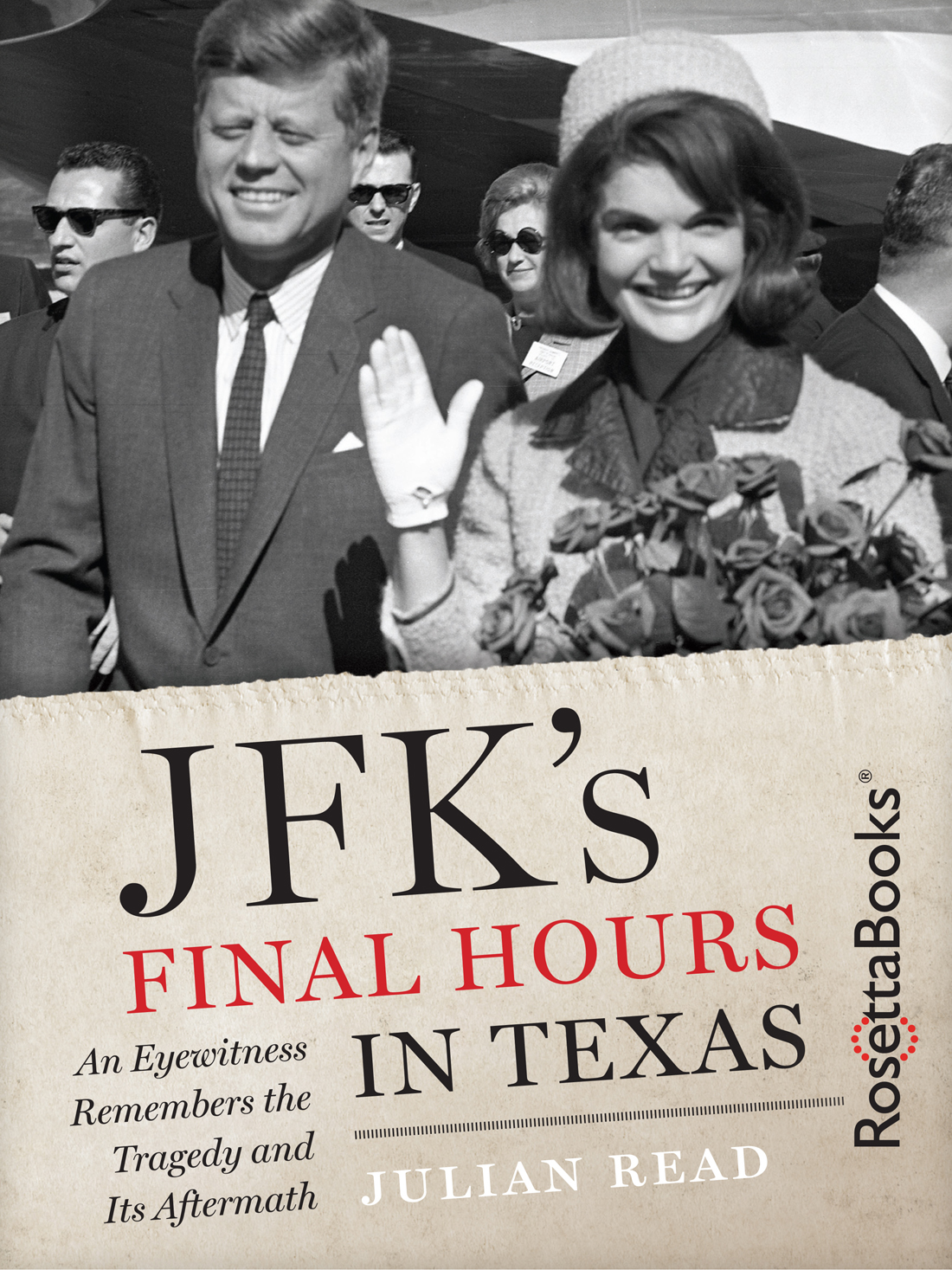

JFKs Final Hours In Texas:

An Eyewitness Remembers the Tragedy and Its Aftermath

Julian Read

Copyright

JFKs Final Hours In Texas: An Eyewitness Remembers the Tragedy and Its Aftermath

Copyright 2013 by Julian Read

Cover art, special contents, and Electronic Edition 2013 by RosettaBooks LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Print book available from the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013949048

Cover jacket design by Derek George

ISBN ePub edition: 9780795335846

Photo, previous pages: President and Mrs. Kennedys joyous arrival at Love Field in Dallas.

Contents

I know Julian Read as a fixture in the world of Texas politics and public affairs and also as a passionate advocate for historical preservation. Hes been a stalwart supporter of the Briscoe Center, and Im proud to say his papers are part of our holdings. I was aware of his close relationship to Governor John Connally and knew of Julians proximity to the historic events surrounding John F. Kennedys final trip to Texas. There are plenty of Texans with their own stories to tell of that November in Dallas, but few with this sort of inside seat to the crisis. So, when Julian approached me to share his memoir, I was immediately intrigued.

Reading Julians recollections evoked my own vivid memories of JFKs final hours in Texas. Like many of my generation, Kennedy was the first candidate who inspired my political awareness. At the age of thirteen, I handed out his campaigns bumper stickers and leaflets at shopping centers in my hometown, Dallas, and skipped school to watch the inauguration on television.

On that fateful day in 1963, the Dallas school district had granted permission for students to leave school to see the president downtown or at Love Field, but I was stranded at home with car trouble. I heard about the assassination while eating lunch and ended up watching Walter Cronkites news coverage. (I would later have the good fortune to call Walter a close friend, and we spoke at length about the death of JFK while working on Cronkites memoirs.) As a resident of Dallas, there were even more personal connectionsfriends and their families were the local police and politicians involved in the aftermath. The infamous photo of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald is notable to me as a historian, but also as a collection of familiar faces from my neighborhood. Those moments were brought back to me as I read Julians retelling of that tragic time.

This memoir would have value if Julian had simply recounted his own experiences during Kennedys ill-fated trip to Texas. But he goes on to provide an important, and often overlooked, aspect of the assassination. What does it mean to be the site of such a tragedy? How does a community negotiate that complex legacy? Julian explores how the public memory of those events has been shaped, from monuments and museums to the annual remembrances of those directly involved. His extensive research and interviews with key figures, paired with his own insiders perspective, have resulted in a compelling book that gives a uniquely Texan perspective to a national tragedy.

Don Carleton

Executive Director, the Dolph Briscoe

Center for American History

Texas Governor John Connally with aides, left to right: Mike Myers, Julian Read, Howard Rose, Connally, Larry Temple, and John Mobley.

On Friday, November 22, 1963, one of the most shocking and tumultuous events in history occurred shortly after noon when the president of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, was struck down by an assassins bullet in downtown Dallas, Texas.

It is difficult for todays generation to fully comprehend the trauma that gripped the nation and the world for days and weeks afterward.

Grown men sobbed shamelessly in public.

Streets were deserted.

Schools and shops were shuttered.

Terrified mothers lowered window shades.

Businesses came to a standstill.

Churches and synagogues were crowded as never before.

Americans were fearful and uncertain as they remained glued to television screens, watching a nightmare that would defy any screenwriters imagination unfold before their eyes.

As a nation, we watched a usually stolid Walter Cronkite brush away a tear as he announced on the CBS television news that the president was dead. With our neighbors we mourned the sight of the presidents body being unloaded from Air Force One at Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington, D.C., while the new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson, stood on the tarmac facing the task of calming an uneasy nation against mounting rumors of conspiracies. Then, less than forty-eight hours later, we were horrified and dumbfounded to see, on live television, the murder of the presidents accused assassin inof all placesthe basement of the Dallas police headquarters. What more could happen?

It all seemed too much for our generation to endure, and the scars of those events did in fact remain for a long, long time.

I was a witness to that momentous tragedy fifty years ago as an aide to Texas Governor John B. Connally, who was the host for the five-city tour that brought the president to Texas, and ultimately to Dallas. I was Connallys representative to an army of news editors and reporters who covered the widely anticipated tour of Texas, the state that had given the Kennedy-Johnson ticket the winning edge in the election of 1960.

Then, for years following the assassination, each and every November I scheduled and coordinated a seemingly endless progression of interviews for Governor Connally with representatives of news media from around the world who repeatedly revived the tragedy on its anniversary date. After Governor Connallys death in 1993, I continued to coordinate the same requests that persisted for his wife, Nellie Connally, until she died in 2006.

But through these many years, I never have shared my personal experiences of that horrendous time that will remain etched in the nations memory and psyche. I now feel, at the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination, that my viewpoint, for whatever it is worth, should be added to the record.

I would ask the reader to be mindful that this is not a book about Julian Read. Its a book about incomprehensibly shattering events that Julian Read, then a thirty-six-year-old campaign consultant early in his career saw, heardlived througha half century ago in Dallas on November 22, 1963.

This is not a book about me, although Im at the center of it and keep popping up in the most unlikely places throughout the account of events that I witnessed on that history-changing weekend and in its aftermath. Even now, as I probe my memory and the memories of those who lived through those days with me and are still able to share them, I find it something of a wonder: why was I even there in the first place?

Next page