THE BOYS OF WINTER

THE Boys OF WINTER

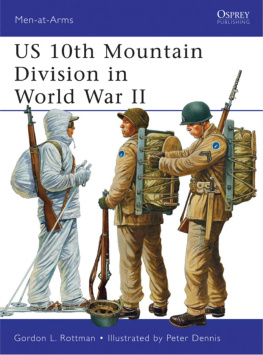

LIFE AND DEATH IN THE U.S. SKI TROOPS DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Charles J. Sanders

2005 by Charles J. Sanders

Published by the University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

All rights reserved

First paperback edition 2005

Printed in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State College, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Mesa State College, Metropolitan State College of Denver, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, and Western State College of Colorado.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sanders, Charles J. (Charles Jeffrey), 1958

The boys of winter : life and death in the U.S. ski troops during the Second World War / Charles J. Sanders.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87081-783-3 (alk. paper) ISBN 0-87081-823-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Konieczny, Rudy, d. 1945. 2. Nunnemacher, Jacob, d. 1945. 3. Bromaghin, Ralph, d. 1945. 4. United States. Army. Mountain Division, 10thHistory. 5. United States. ArmySki troops. 6. World War, 19391945CampaignsItaly. 7. World War, 19391945Regimental historiesUnited States. 8. SoldiersUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

D769.310th.S26 2004

940.54451092273dc22

2004017421

Design by Daniel Pratt

Typesetting by Laura Furney

14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Every reasonable effort has been made to obtain permission for all copyrighted material included in this work. Any errors that may have occurred are inadvertent and will be corrected in subsequent editions, provided notification is sent to the publisher.

For my father,

my son,

and those boys of winter

to whom the gift of long life was denied

I hope they will remembernot with sackcloth, not with tearsbut just by contemplating a little, what these men gave, willingly or not, has contributed toward an opportunity still to travel the trails.

DAVID BROWER (10th Mt. Div.), The Sierra Club Bulletin, 1945, in For Earths Sake: The Life and Times of David Brower

See again in your minds eye the handsome suntanned facea quiet smile on his lips, a twinkle in those dark eyes squinting into the sun. Recall with me in happy memory those mountain daysof sunshine and snow, of ski races wonand lost; of pitches on steep rock faces, summits gainedof retreats from storms and danger; of less happy yet wonderful days of army service, of combat in Italy, of comrades lost but victory gained; of fireside songs, of the Winter Song itself, which always ends in the pledge of fellowship, of fellowship.

ERLING OMAR OMLAND (10th Mt. Div.), Eulogy for

Sergeant Walter Prager, 1984, in Leaves from a

Skiers Journal, New England Ski Museum Newsletter

Montani Semper LiberiMountaineers Are Always Free.

LOWELL THOMAS, Book of the High Mountains

Contents

FOREWORD

by Major John B. Woodward, Tenth Mountain Division (Ret.)

Illustrations

MAPS

PHOTOGRAPHS

PREWAR, following page 72

TRAINING IN WASHINGTON AND COLORADO, following page 116

THE WAR IN ITALY, following page 192

Foreword

IT WAS IN THE YEAR 2000, ON A TENTH MOUNTAIN DIVISION REUNION TRIP TO Italy, that I experienced a startling moment of grief that bears directly on my feelings for The Boys of Winter and its poignant subject matter.

Beta Fotas was a young skier from my hometown of Seattle. As one of the senior officers of the Eighty-seventh Mountain Regiment, the Mountain Training Center, and later the Tenth Recon/Mountain Training Group, I had the opportunity during the early 1940s to oversee his training at Mount Rainier and later at Camp Hale, Colorado. He was a fine young man, always ready to do whatever task might be assigned to him. Everyone liked Beta and admired his mountaineering skills. I thought of him as one of the truly good kids I had the privilege to mentor during my years of army service.

Though I have kept in contact over the years with a good many veterans of the division, especially those like myself who continued to be avid skiers after the war, I assumed that Beta was among the men who preferred to put their combat experiences behind them by limiting their ties to former comrades in arms. I was certain that he had made it all the way through to the end of our campaign, moved from Seattle, married, raised a family, and gone on with his life. Perhaps he still skied and climbed with his grandchildren, I hoped, whenever thoughts of him crossed my mind.

One of the highlights of our reunion trip to Italy was a visit to the Florence Military Cemetery, where many of our friends are buried. Though the families of the majority of the boys killed in action opted to bring their loved ones home for reinterment, others believed it was better to let their sons rest in the land where they died (we hope not in vain), with the buddies with whom they served.

When our tour group arrived at the cemetery, we found a touching tribute in the form of a single rose placed at the foot of each Tenth Mountaineer grave marker, allowing us to find our friends among the thousands of American servicemen and -women from other divisions buried there. We passed among the rows of markers, paying our respects, here and there recognizing a name that set off a rush of memories and emotions.

And then I passed one cross with a rose resting beneath it, and glanced up to read the inscription. I can only describe my feeling upon seeing that name as a brutal shock. I was standing before the grave of Beta Fotas, killed in action on April 14, 1945. There had been, it turns out, no joyful homecoming for Beta, no family life after the war, no rewarding career, and no leisure time spent in the mountains. Those were legends I had optimistically created and taken comfort in for more than fifty years. Having them evaporate in a single instant drove home again the very painful reality that every combat veteran knows but tries hard not to dwell on: Beta Fotas had given everything. Unexpectedly finding his resting place stayed in my mind for the rest of the trip, and has remained with me ever since.

There was a time when a book delving into the innermost, personal feelings of the men of our division during our months of combatespecially of those who did not come homemight have been viewed by the divisions survivors as needlessly intrusive. With the passage of time, however, priorities often shift. At some point, the desire to honor fallen friends in order to ensure that their very personal sacrifice is remembered surpasses the desire to protect the unique privacy of the battlefield.

It was my honor to know all the young men whose lives are painstakingly recounted in The Boys of Winter. As with Beta Fotas, I can say without exaggeration that they were among the most exceptional individuals I have ever known, and I am extremely gratified that their stories are now memorialized in print.

Next page

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992