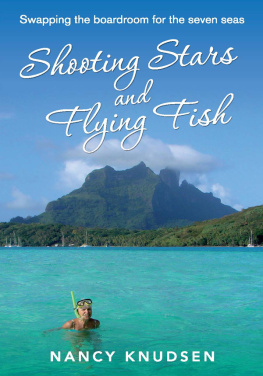

T HE LIGHTS GO DOWN IN THE PACKED-OUT N EW Y ORK C ITY CONCERT hall. From my front-row seat next to my wife, Nancy, I look up to see myself suddenly projected onto a huge screen above the stage. The video instantly transports a glamorous, star-studded celebrity audiencedressed to the nines in diamonds, designer dresses, and tuxedosaround the world to a rural Kenyan hillside where a video-me stands looking out over the Great Rift Valley. And my amplified voice fills the auditorium, saying, Africa will change you. Africa gets under your skin and wont let go. The screen shot shifts from a rural setting to an African street scene as my voice-over continues. We were a typical American family I cringe to see my own much larger than life image, speaking and moving across the screen. I listen to my voice drone on and make what sounds in this moment to be a public confession: My wife has always wanted to be in Africa; I never wanted to be in Africa.

A part of me cant help marveling at what is happening to me here tonight, at a live television event being broadcast around the world. Yet a bigger part of me almost has to laugh out loud at what feels like just another very strange chapter in a strange life that is no longer my own and hasnt been for almost a decade.

Then a young makeup artist crouches down beside me and hurriedly tries to make me presentable for my acceptance speech. I want to tell her she has a hopeless job. Instead, I bite my tongue. And as she goes about her business, I determine to refocus on the screen and review in my mind the words Ive written out to say.

When the attentive young lady whispers, We cant have you looking all shiny up there, and begins powdering my entire countenance, three nearly simultaneous thoughts arise in my mind: Ive never before in my life worried about being all shiny, whatever that means. Its hard, if not impossible, to focus your thoughts on anything else while a makeup artist is powdering your face. And, I have found myself in more than my share of weirdly unsettling situations before, but this feels weird on a much bigger, harder-to-believe scale!

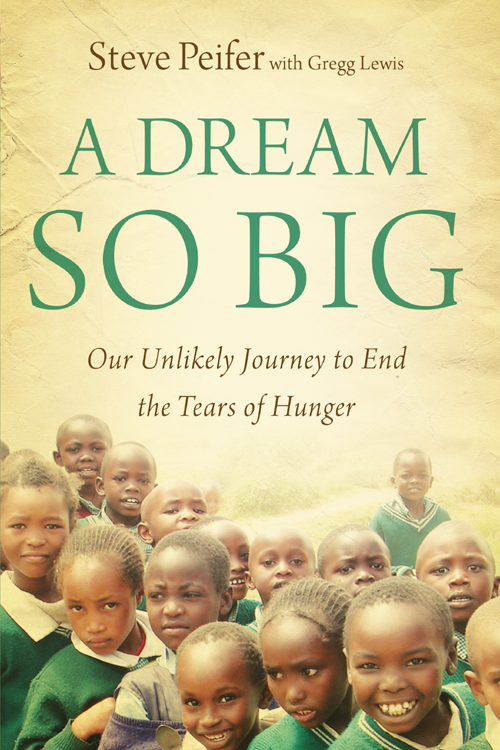

As the video rolls on, my mind wanders. How does the college guidance counselor at a hundred-year-old, rural Kenyan boarding school for missionary kids ever get nominated for, let alone win, the annual CNNs Hero for Championing Children Award? For that matter, how in the world did a guy living a normal American lifecomplete with a wonderful, loving wife, two terrific kids, a nice big house, and a solid career as a corporate manager with one of the worlds leading technology giantsfind himself residing on the far side of the earth feeding lunch and teaching computer skills to hungry African schoolchildren, some of whose families still hunt with spears and live in mud-hut villages without electricity or running water?

The answers to all those questions require a story that does not begin at a glitzy gala in New York City. Neither does the story end as the screen goes dark, the house lights come back up, and Tyra Banks, one of the worlds most famous fashion models and now also a television show host, stands at the microphone saying, It is my honor to present the CNN Hero for Championing Children, Steve Peifer.

That night, as unreal as it felt at the time, as nice an honor as CNN made it on such a big stage, is a small, albeit memorable, scene in a much larger real storya personal and family pilgrimage that began more than ten years before and far beyond the bright lights and big city. A story that has taken me to many places and situations where I have had to do what I did that special night in New York: stop, look around, pinch myself to see if I was dreaming, and wonder, How in the world did I get here?

1

What in the World Am I Doing Here?

T WO CONTRASTING YET INTERRELATED FEELINGS HIT ME THE MOMENT I walked through the exit doors of the terminal at Nairobi International Airport at 6:00 a.m. and stepped into Africa for the first time. Number one was the worst, most exhausting case of jet lag Id ever experienced. The second was a sudden, heightened awareness of my own alienness.

After a twenty-eight-hour journey from the United States, including a fifteen-hour layover and whirlwind tour of London, with my wife, Nancy, and our seven- and ten-year-old sons (whod had all of six hours of sleep over the previous two days) in tow, I understood the exhaustion. I was simply glad to have survived my very first international travel experience and have all eight pieces of our luggage arrive in Kenya with us.

What caught me by surprise was how suddenly and totally out of place I felt. We definitely werent in Kansas anymore. Id lived in Kansas for a few years before I moved to Texas. And Nairobi wasnt anything like anywhere Id ever been before.

Most of the hour-and-a-half drive to our final destination remains a blur on my memory screen. Any travel-guide spiel offered by the man who met us at the airport and drove us out to Kijabe went right over, or in and out of, my head, although I clearly remember that I found driving on the left side of the road so disconcerting that I couldnt count the number of times I flinched in anticipation of a horrendous crash.

But a few of the sights and sounds and smells of Africa penetrated the fatigue enough to leave some lasting impressions. All of which fed my out-of-place feeling. Every direction I turned, everything I saw looked so so foreign.

More than three million people live in Nairobi, Kenyas capital and largest city. Most of them seemed to be out walking shortly after dawn on this weekday morning. The rest rode in matatus (privately owned vans and minivans) that serve as the countrys primary mass transportation. As many as thirty Kenyans will pack into a van built to hold nine people comfortably; I saw some matatus with riders on top and others with outside passengers standing on running boards or hanging from luggage racks or clinging to open and swinging back doors.

Neither drivers nor pedestrians hesitated to cross multiple lanes of moving traffic wherever and whenever they wanted. Then there were the donkey carts using the same lanes as motorized vehicles. And the chickens, goats, and sheep that wandered all over the place.

The city was so crowded and dirty, even the new buildings looked tired. Vendors peddled anything and everything you can imagine (and some you cant) in what looks like an endless roadside flea-market. The farther you get from the downtown business district, the more frequently you see and smell trash burning right along the streets. Somewhere between one and two million people make their homes in Nairobis slums, living in sheet-metal shacks with dirt floors.

Even if you arent a big city fan, you can enjoy the energy of New York, the vitality of Chicago, the diversity of San Francisco. It was hard to find anything in Nairobi to appreciate, except for the more than three million individuals who live there in some of the most deplorable conditions you can imagine.

When I managed to look past the constantly moving mass of people walking along, and back and forth across, the roadways to focus on one person at a time, what I saw was even more unsettlingyoung kids the age of our JT and Matthew carrying around large jars of glue, sniffing all the time. And as I looked more carefully, I was amazed by how many people I noticed in the backgroundsitting, staring, and going nowhere. There seemed to be no hope in their eyes.