Many people were helpful in researching this book. Two of the most historic areas of Dublin are covered and consequently I am very grateful to individuals and residents of these areas for their help. Hell was located on the fringes (in more ways than one) of the Liberties, and Councillor John Gallagher of the Liberties Heritage Association was a guiding light and inspiration. He fought the good fight on the Wood Quay issue for decades (see my book The Liberties , 2013). He also fought many other battles for the people of his beloved community. In the Monto area, like the Liberties, one individual also stands out Terry Fagan. A special thanks to Terry and the North Inner City Folklore Project. Terry Fagan is not your typical folklorist; but then again, Dublins Monto and its people are not typical subjects. Born and reared in Corporation Buildings, the heart of the one-time notorious red-light district, Monto, Terry has written much on the area over the years. With all these new developments that are springing up around us, we feel it is important for something to be preserved and documented before the whole place fades into history, he argues. A graduate of the Redbrick Slaughterhouse, Rutland Street School, Terrys determination to bring to life the history of this fascinating part of Dublin came to fruition in his writings and history-promoting activities in the area. Terry Fagan is truly a walking encyclopaedia about all things Monto. Growing up in the area has given him first-hand experience of the many changes, bad and good, visited upon this unique area in Dublin. Not only that but he personifies the distinctive and unquenchable spirit of Monto, a spirit that was much in evidence in 1913, 1916 and the War of Independence, and that has played a hugely important part in modern Irish history. Des OHanlon of the famous old historic pub, Clearys, also made me feel very welcome, as did the Monto Barber on Amiens Street.

Thanks to Alan OKeefe of the Herald for information on Darkey Kelly. Of immeasurable help and inspiration was John Finnegan, who wrote articles on Monto in the Evening Herald in April 1972, which subsequently became the book The Story of Monto . Likewise my thanks go to Larissa Nolan of the Irish Independent and Lisa-Marie Griffith. Eamon McLoughlin, the radio producer of the documentary No Smoke without Hellfire , and fellow researcher Phil OGrady were helpful with information about Darkey Kelly, as was Charles Gregg with his song about Darkey Kelly called Second Class Woman. Karyn Moynihan, of the Womens Museum of Ireland, provided much information on Margaret Leeson. Mary Lyons has done much service, particularly for her work on Margaret Leeson. D. Fallon of the Come Here to Me history blog was helpful on many aspects of Dublins history. Mark Simpson was helpful for his detailed information on the madams of Monto. Thanks also to Niamh OReilly of the Global Womens Studies Programme, NUI Galway, for her documentary Three Hundred Years of Vice . I am also grateful to David Ryan and Michael Fewer for their landmark work on the Hellfire Club. Thanks to Maggie Armstrong of the Irish Independent for her observations that the squalor and brothels of Monto were a large part of James Joyces Ulysses . Director Louise Lowe and designer Owen Boss of Anu Productions have done much in recent years with their extraordinary yet disquieting theatrical presentation of a four-part history of Monto called The Monto Cycle . Thanks also to Harold Beck and John Simpson for their research on James Joyce; their work on the madams deserves particular praise and I found their notes indispensable. Senator David Norris and Peter Costello added much to my understanding of James Joyce. Grateful thanks in particular to the legendary Oliver St John Gogarty biographer, Ulick OConnor, for his kind permission to use Gogartys material. Thanks also to Dr Maire Kennedy in Dublin City Libraries and Archives, and the very helpful staff in Pearse Street Public Library deserve particular gratitude. June OReilly, with the able help of Larry and Nuala, was of immense help with her photographic skills. I am very grateful also to Ronan Colgan and Beth Amphlett of The History Press for their constant encouragement, skills and indefatigable patience. Finally, my gratitude goes to the people of the Liberties (wherein Hell is to be found) and Monto for their help, friendliness and encouragement.

CONTENTS

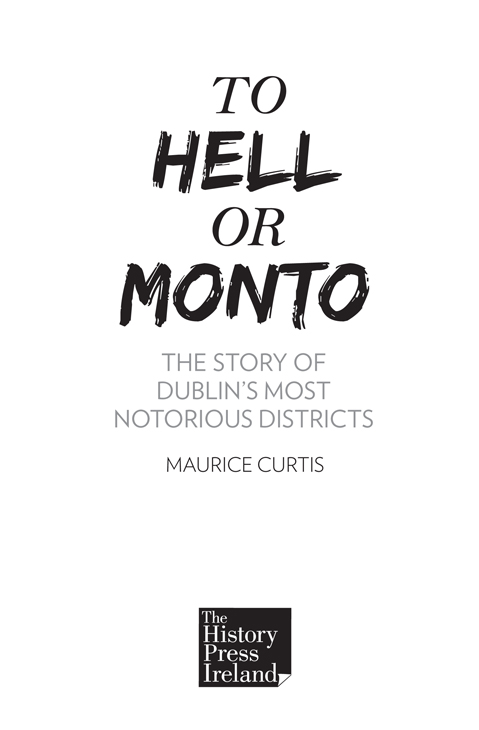

This book looks at two of the most infamous and notorious red-light districts in Dublin: Hell and Monto. Hell was the centre of vice, gambling, duelling, rowdy taverns, bawdy houses and other disreputable activities in the eighteenth century. Monto took over the mantle in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Hell was located along the lanes and alleyways at the front and back of Christ Church Cathedral and extended from Cork Hill, Copper Alley/Fishamble Street, Johns Lane East, St Michaels Hill/Skinners Row (now Christ Church Place), Winetavern Street and to Cook Street. Monto was located between Amiens Street and Lower Gardiner Street, between Sean McDermott Street and Lower Talbot Street and only a short walk from OConnell Street and Dublin Port.

Hell was identified on Rocques Map of Dublin, 1756 and the name was in common usage in the eighteenth century and beyond to describe an area of notorious taverns (e.g. Winetavern Street, so called because of the large number of ale and wine houses), brothels and gambling houses that were clustered together, essentially in the shadow of the cathedral and the old walls of Dublin. This was where Dublins prostitutes, pimps, cutpurses, rakes and murderers houses were to be found. Darkey Kelly, Pimping Peg, Molly Malone, disreputable taverns and coffee-houses as well as the Smock Alley Theatre and the infamous Hellfire Club were all associated with Hell.

Though the name Monto has endured in folk memory, it was not the first major brothel area in Dublin. Hell was equally notorious, feared and renowned in its day. And like Monto, the police (watch) dared not venture in! It was in the early eighteenth century that the cobbled streets and laneways were laid out around Copper Alley, Smock Alley, Fishamble Street and the surrounding area, on land acquired by William Temple (15541628). This included the former lands of the Augustinian friary that had stood here for nearly 500 years until the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII. Once the monks had departed the taverners, publicans and prostitutes stepped in, and for a century or so thereafter, until the very late eighteenth century, it and the wider area in the immediate vicinity of Christ Church Cathedral had a very disreputable reputation and were known far and wide as Hell.

Monto took over from Hell with the demolition of the old lanes and alleyways around Christ Church Cathedral in late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries. This was the work of the Wide Streets Commissioners, who wished to abolish the old medieval lanes and alleys that dominated old Dublin, and where prostitution flourished. However, their changes just resulted in prostitution moving to new quarters in the city and soon Monto was full of brothels and houses of ill repute. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries Monto was the most famous red-light district in Dublin, possibly Europe. However, the name Monto never appeared on any map as it was the nickname. The name is derived from Montgomery Street (now called Foley Street), which runs parallel to the lower end of Talbot Street, towards what is now Connolly Station.

Next page