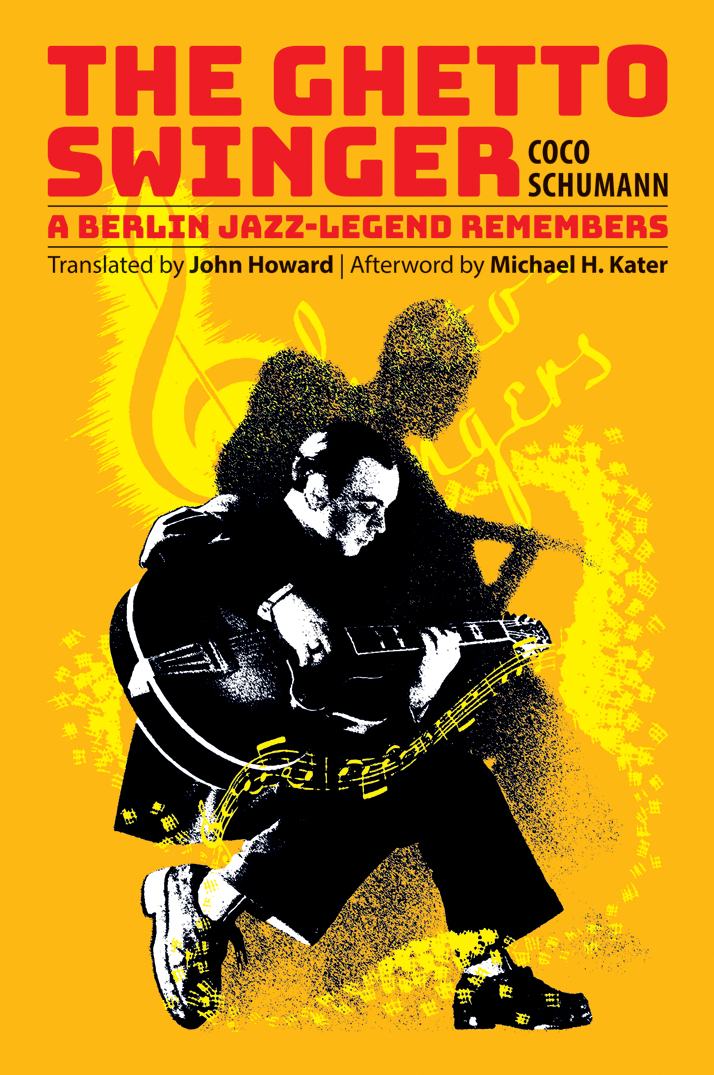

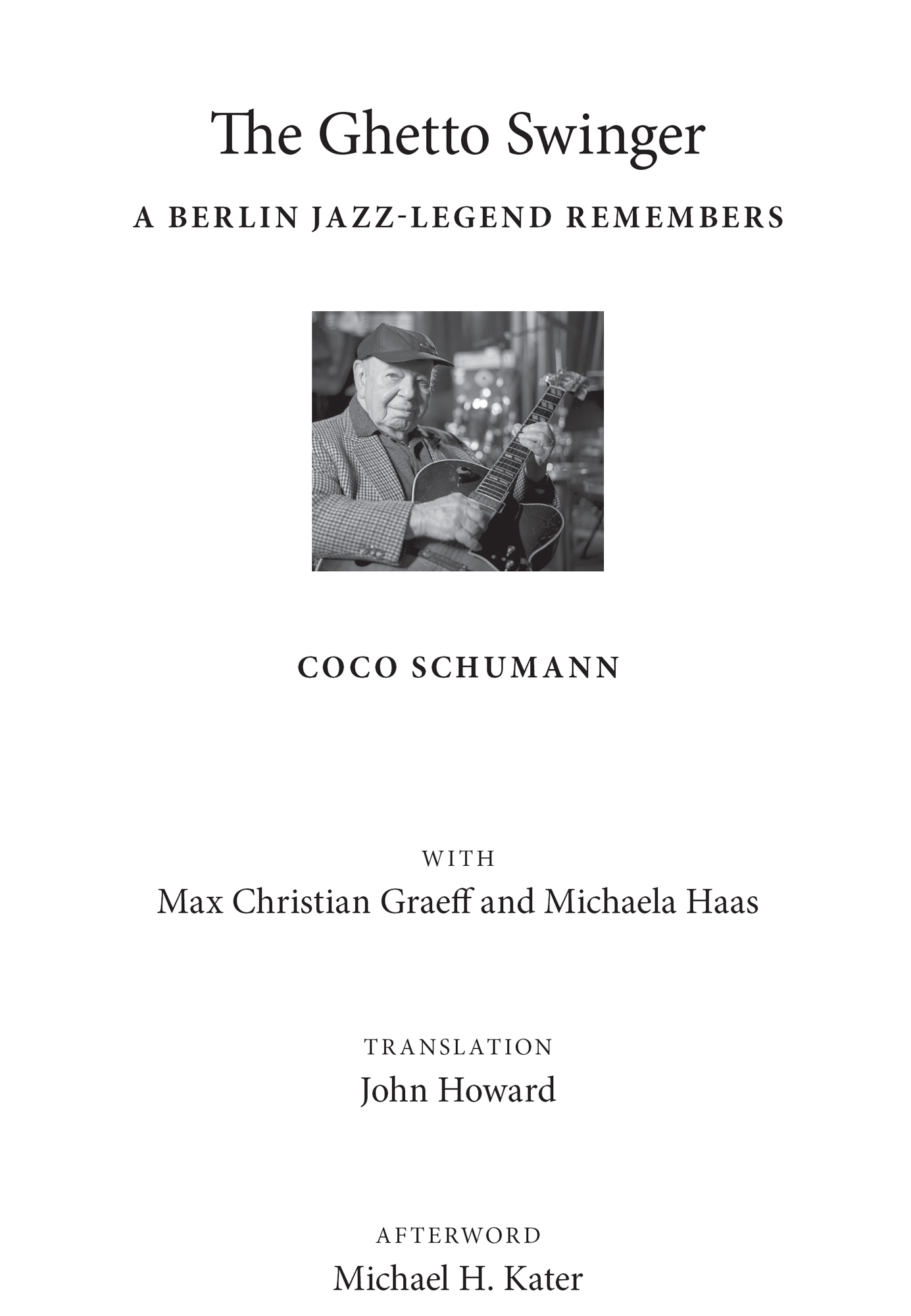

The Ghetto Swinger

A BERLIN JAZZ-LEGEND REMEMBERS

Coco Schumann

WITH Max Christian Graeff and Michaela Haas

1997 Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich/Germany

TRANSLATION John Howard

AFTERWORD Michael H. Kater

ENGLISH TRANSLATION 2016 DoppelHouse Press, Los Angeles

BOOK DESIGN Curt Carpenter

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Photographs from the archive of Coco Schumann, unless otherwise noted.

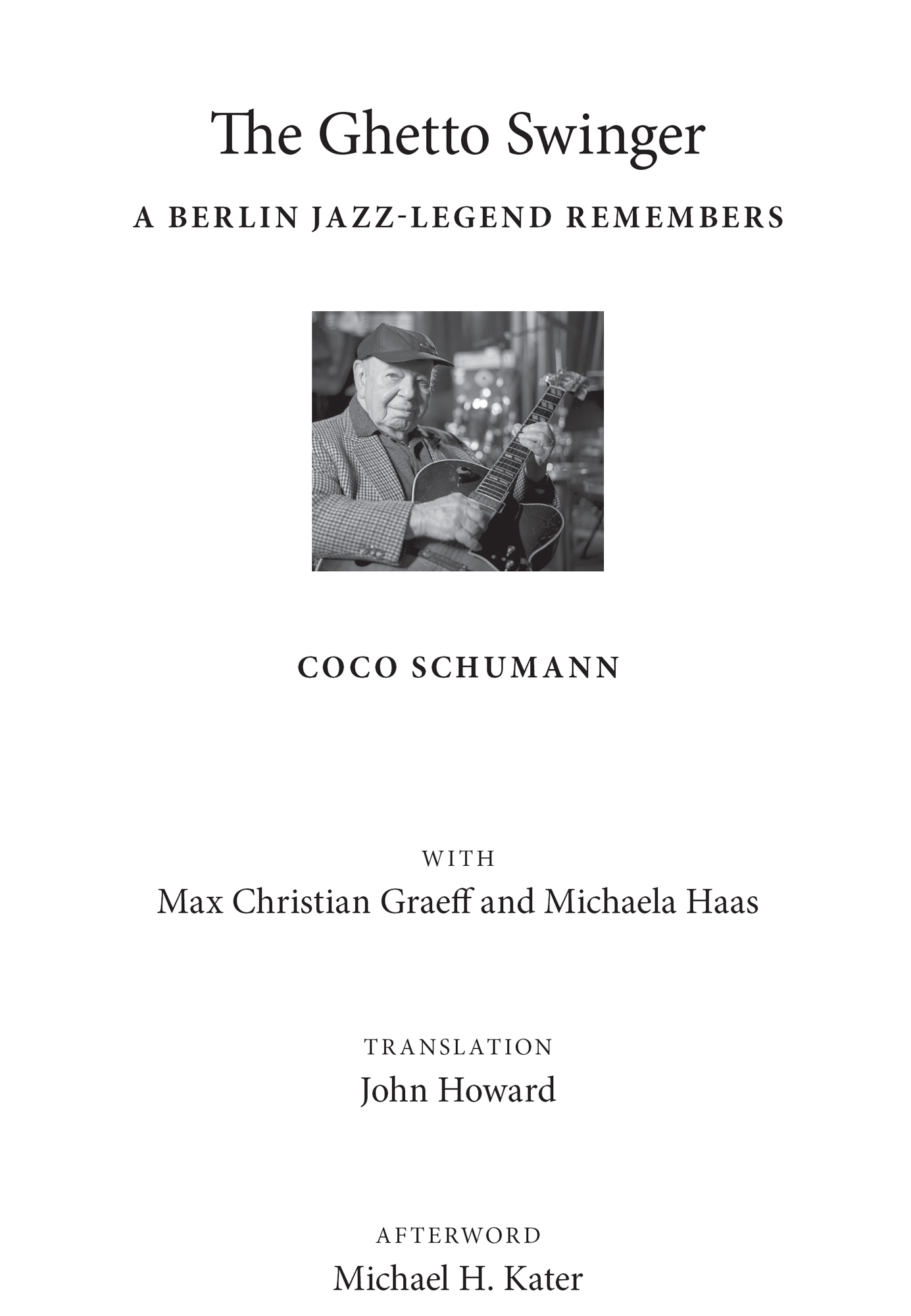

TITLE PAGE: Coco Schumann, 2014. PHOTO: Susann Welscher

Publishers Cataloging-in-Publication data

NAMES: Schumann, Coco, 1924-, author. | Graeff, Max Christian, contributor. | Haas, Michaela, 1970-, contributor | Howard, John, 1942-, translator. | Kater, Michael H., 1937-, afterword author.

TITLE: The Ghetto Swinger: a Berlin Jazz Legend Remembers / Coco Schumann; with Max Christian Graeff and Michaela Haas; translation [by] John Howard; afterword [by] Michael H. Kater.

DESCRIPTION: Los Angeles, CA: Dopplehouse Press, 2016.

IDENTIFIERS: ISBN 978-0-9832540-6-5 (ebook) | LCCN 2015948459

SUBJECTS: LCSH Schumann, Coco, 1924-. | Jazz musicians--Germany--Biography. | Swing (Music)--Germany. | Guitarists--Germany--Biography. | Jews--Germany--Biography. | World War, 1939-1945--Personal narratives, Jewish.

BISAC BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Music

BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Historical

BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Jewish

CLASSIFICATION: LCC ML419.S33 A3 2016 | DDC 787.87/165/09dc23

If I hadnt been six-foot five, blond and Germanic, I never would have made it through all this.

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

I HAVE PLAYED GUITAR and percussion since I was thirteen years old. At the beginning of the 1940s, I played as a guitarist in many clubs in Berlin. At the time, I was a star in the Berlin swing scene, even when the Nazis banned this music. No one knew that I was Jewish. It was forbidden for Jews to play music and to have contact with Aryan Germans. It was mandatory to wear the yellow Star of David. I did not adhere to these prohibitions and obligations, and I was betrayed. At the age of nineteen, in 1943, I was deported to Theresienstadt ghetto, and at twenty, I was sent to the concentration camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau. In this book, I tell you how music saved my life.

The camps and the fear changed my life, but the music has kept me going, and has made everything good again. I have survived. I am a musician who spent time in concentration camps, not someone in a concentration camp who also played a little music.

It was much later, in the mid-1980s, that I began to talk about my time in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz-Birkenau in films, in the media and in schools. As a young person, I could not believe what some people were capable of inflicting on others. I have learned that we must never allow ourselves to bend based on others views. What matters is ones own convictions and mutual respect, regardless of race, color, religion and political points of view.

In 1997, my book The Ghetto Swinger was published, which is now being published in English. I am very happy about this.

Coco Schumann

BERLIN, MARCH 2015

Me on the left in front of the Gedchtniskirche in Berlin, circa 1942, with my friend, the pianist Herbert Giesler. Against regulations, I have my Star of David in my pocket. The scratches on the photo remain a mystery.

T HE FINAL NOTES of How High the Moon fade away. A warm night in August. After the applause dies, I put my old Gibson guitar to one side, step to the front door of the nightclub, the Ewige Lampe (Eternal Lamp), and look up at the sky above Charlottenburg. The moon sits high over the houses and beams down on me this evening, mirroring my own worries. Its gotten very late again is this proper for a man my age? I asked myself this question sixty years ago when I was a twelve-year-old who loved to party the nights away. The major part of my life spanned those two points in time. A picture of me was published in a popular newspaper with the words Coco Schumann: The Terrible Life of a Jazz Legend! But it was not true. No, my dear fellow, I tell myself facing the bright moon; it was wild and flamboyant, sometimes too long and always too short, but life has turned out both unbelievably evil and so beautiful it takes your breath away. However, one thing it certainly never was: terrible.

The reporter who wrote those words did not intend to be cruel; quite the opposite. Those words reflect one of the misunderstandings that popped up when I told the story of my life because there were a few years that didnt just change me, they changed the world. I am a child of my times and as such, being also Jewish, I spent a few years in a Nazi concentration camp, like millions of other people. My life could easily have come to an early, very sudden end. For a brief period that seemed to go on forever, I couldnt be sure there would be a tomorrow. I am grateful right up to this day that tomorrow did come, that it kept coming until the danger passed. This feeling of gratitude has never left me. Unlike millions of others, I survived. I didnt want to talk about it and was not able to until forty years after the fact.

O UR TEACHER had asked each of us to bring five pennies to school. A couple of days later we stepped into the classroom with our pennies in our pockets. A large rhomboid-shaped board with holes drilled into it was leaning against the blackboard. We lined up in rows and waited quietly. One after another, my classmates bought a nail with their pennies, a nail that had a big brass head. They stepped up to the board and nailed it into one of the holes in the board. Our teacher explained that what was taking shape here before our eyes with every one of us making a contribution was a new alliance, the Hitler Youth, and that all of us were now fellow members. All of us, I thought until it was my turn. When I went up to buy my nail, the teacher stopped me. In front of the whole class, he told me I was a Jew and that Jews could not join. I stared at him but did not understand, went back to my desk and sat down. It was the first time somebody had told me that I was a Jew and that I was not what I thought I was a German, a friend, a part of what was going on in my country.

After school, I slouched home, devastated. At first I thought the teacher was mad at me because of a joke I had once played on him. He had tried to create a good atmosphere in the classroom by announcing he would only shop at our parents businesses. I told him to be sure to shop at my moms place. The joke was that he was bald and did not know my mom owned a hair salon! That evening my parents explained very carefully what these new times were all about. I was too young to understand or maybe I did not want to understand. At first I just thought the teacher had it in for me, but my classmates soon helped me comprehend the situation. I had gotten along with them just fine before, but now they insisted on a previously unknown difference between them and me.