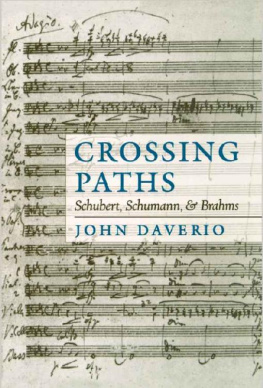

Schumanns Virtuosity

ALEXANDER STEFANIAK

Schumanns Virtuosity

Criticism, Composition, and Performance in Nineteenth-Century Germany

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Bloomington & Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2016 by Alexander Stefaniak

Publication of this book was supported by the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stefaniak, Alexander, 1983 author.

Title: Schumanns virtuosity : criticism, composition, and performance in nineteenth-century Germany / Alexander Stefaniak.

Description: Bloomington ; Indianapolis : Indiana University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016021002 (print) | LCCN 2016021399 (ebook) | ISBN 9780253021991 (cloth : alkaline paper) | ISBN 9780253022097 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Schumann, Robert, 18101856Influence. | Virtuosity in musical performanceGermanyHistory19th century. | MusicGermany19th centuryPhilosophy and aesthetics.

Classification: LCC ML410.S4 S83 2016 (print) | LCC ML410.S4 (ebook) | DDC 780.92dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016021002

1 2 3 4 521 20 19 18 17 16

For Eliana, a poetic virtuoso

Contents

Acknowledgments

Perhaps the most rewarding aspect of writing this book has been meeting and working with many generous, kind people who have helped the project along at various stages. I especially owe thanks to several archivists who shared sources from their collections, guided me through their holdings, and extended their hospitality during my research trips: in particular, Thomas Synofzik and Hrosvith Dahmen of the Robert Schumann Haus in Zwickau, Matthias Wendt of the Robert-Schumann-Forschungsstelle in Dsseldorf, and the staff of the music reading room at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich.

Numerous friends and colleagues in musicology and other disciplines gave freely of their expertise and provided moral support. Ralph Locke, Bill Marvin, and Holly Watkins were instrumental in shaping this books methodological pluralism. At Washington University in Saint Louis, Ben Duane, Denise Gill, and Paul Steinbeck read several of chapters, and the universitys Eighteenth-Century Interdisciplinary Salon (led by Tili Boon Cuill) workshopped . Brad Short of Gaylord Music Library tirelessly acquired resources important for my work. Other friends and colleagues in Saint Louis and elsewhere commented on sections of the book or answered specific queries: Jonathan Bellman, Julie Hedges Brown, Todd Decker, Matt Erlin, Catherine Keane, Caroline Kita, Jonathan Kregor, Karen Leistra-Jones, Att and Robert McDowell, Laurie McManus, Craig Monson, Dolores Pesce, Robert Snarrenberg, Hanne Spence, Marie Sumner Lott, Lynne Tatlock, and Kira Thurman. All shortcomings, of course, remain my own.

Some individuals and institutions granted me permission to quote extensively from sources to which they hold rights. Claudia Macdonald allowed me to draw a music example from her edition of Schumanns F-Major Piano Concerto; Hofmeister Verlagto draw a music example from their edition of Schumanns Sehnsuchtwalzer Variations; and Thomas Synofzikto publish my translation of Schumanns epilogue to his Ein Opus II essay. A version of has appeared in Journal of Musicology 33, no. 4 (2016).

Raina Polivka and her colleagues at Indiana University Press have steered this book steadily through review and production. Janice Frisch, Naz Pantaloni, and my anonymous readers were especially helpful in the earlier stages, and David Miller and Mary Ribesky oversaw production. Eileen Allen prepared the index. Washington University PhD student Joseph Jakubowski engraved the music examplesno small feat, given the complex piano texturesand Karen Olson proofread them with an eagle eye.

Finally, my family has been at my side from the beginning of this project. My parents, Martha and Carl, and my brother, Andy, have always supported my musical and scholarly endeavors and were ever ready to hear more about nineteenth-century virtuosity and the writing process. My wife, Eliana Haig, was behind this book in ways big and small, sharing every day her ready humor, infectious curiosity, unsinkable confidence, and musicians ear.

Schumanns Virtuosity

Introduction: The Virtuosity Discourse

In 1843, Robert Schumann published a review that captures, in miniature, the range and urgency of the issues that virtuosity raised for him. The essay covered violinist Antonio Bazzinis May 14 concert at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. Its opening does not bode well for the Italian star: Schumann seems to announce himself as a staunch antivirtuosity critic. He describes a horde of virtuosos glutting the concert scene and suggests a sweepingly negative view of their work:

The public has lately begun to notice a surplus of virtuosos, and so has this journal (as it has often made known). Their recently arisen desire to travel to America seems to indicate that the virtuosos themselves feel this, and there are many of their enemies who harbor the silent wish that, for Heavens sake, they will all stay over there. For, all things considered, the newer virtuosity has contributed but little to the benefit of art.

And yet, in his next breath, Schumann claims that Bazzini himself stood apart from this multitude. But when virtuosity confronts us in as delightful a form as the above-mentioned young Italian, he wrote, we gladly listen to it for hours. The rest of the review suggests diverse ways in which Bazzini, for Schumann, redeemed virtuosity. Schumann praises Bazzinis compositions, specifically his Concertino in E, Op. 14: The natural flow of the whole the really enchanting luster and euphony of individual passages most virtuosos have barely any idea of these things. He describes Bazzinis stage presence, his strong, youthful face that provided a welcome contrast to world-weary, pale virtuoso figures. He acknowledges Bazzinis nationality and distanced him from stereotypes of Italian frivolity, calling him an Italian through and through, but in the best sense. Schumann also surely recognized that, on this occasion, Bazzini was lending his star power to an orchestra that had become an exemplar of serious programming under Felix Mendelssohns baton. At times, Schumann did worry that Bazzini stumbled off this pedestal and delighted the crowd with merely physical stunt-artistry. Schumann chided him for programming his Fantaisie dramatique on themes from Donizettis Lucia di Lammermoor and his Capriccio on themes from Bellinis I Puritani. In both of the following pieces, he complained, I saw unhappily that he was not ashamed of flattering the public. Here was not so much

This review represented one small episode in Schumanns lifelong effort to shape what I call the virtuosity discourse: a lively, at times acrimonious discussion in which musicians and writers debated the imagined distinctions between transcendent and superficial virtuosity. Participants ranged across Europe and included often-anthologized writers such as Schumann himself, Franois-Joseph Ftis, Eduard Hanslick, Heinrich Heine, Franz Liszt, A. B. Marx, and Richard Wagner, but also myriad anonymous reviewers of sheet music and concerts. In its most basic definition, virtuosity entailed an extraordinary display of physical skill from the performervelocity, power, facility, even the ability to invent and execute radically new sounds. As the Bazzini review illustrates, Schumann and his contemporaries examined virtuosity in various guises. In some cases, they viewed virtuosity in soloists live performances or public images. In others, they considered how musical compositions scripted virtuosic display. Often, these works came from genres that conventionally promised flashy passagework and were designed to show off or train a performer, such as concertos, etudes, variation sets, and opera fantasies. In still other cases, writers emphasized broader musical practices or abstract aesthetic questions, such as trends in concert programming or ideas about how a performance should relate to a musical work. Schumanns review also illustrates that virtuosity could take on a variety of cultural and aesthetic meanings within these different contexts.

Next page