Robert Schumann

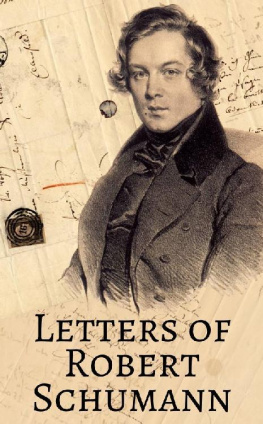

11 Robert Schumann at 29lithograph by Joseph Kriehuber.

(Photo AKG London.)

ROBERT SCHUMANN

Herald of a New Poetic Age

JOHN DAVERIO

Oxford University Press

Oxford New York

Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogot

Bombay Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Dar es Salaam

Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne

Mexico City Nairobi Paris Singapore

Taipei Tokyo Toronto

and associated companies in

Berlin Ibadan

Copyright 1997 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.,

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Daverio, John.

Robert Schumann: herald of a new poetic age / John Daverio.

p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-19-509180-9

1. Schumann, Robert, 1810-1856. 2. ComposersGermanyBiography.

I. Title.

ML410.S4B38 1997

780.92dc20

[B] 96-23177

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

For my parents

Preface

Shortly after completing the draft of this book, I reread one of my favorite essays: Roland Barthess Loving Schumann. Like the French critic, I, too, must confess to loving Schumann, even at the risk of leaving myself open to the charge implicit in this odd passion: the adoption of a philosophy of nostalgia or untimeliness, as Barthes puts it. Moreover, the Schumann I love is the whole Schumannnot the one known to most everyone, the dreamy composer of quirky piano pieces and gorgeous songs who met a tragic endand this Schumann, like caviar, is something of an acquired taste. After receiving a gentle nudge from Maribeth Anderson Payne, my editor at Oxford University Press, I decided to write this biography in part to set aside some old mythsthat Schumann knew how to write short pieces but not long ones, that we can hear traces of his final illness in his later musicbut also, and apart from any polemical intent, to draw a portrait of a composer who was perhaps the first in Western musical history to view the art of composition as a kind of literary activity. And above all, I felt the need to repay a debt, a debt to an artist who has given me untold happy hours as a listener to and performer of his music over the past twenty years. Loving Schumann may be a nostalgic and untimely avocation, but it exacts a price.

Although Im sure to make some omissions, I would like to thank the many colleagues, friends, and students who have helped me to make good on my debt. Fellow Schumannians Arnfried Edler, Jon Finson, Rufus Hallmark, Claudia Macdonald, Gerd Nauhaus, Nancy Reich, R. Larry Todd, and Markus Waldura all offered much-appreciated advice at various stages during my research. I thank Barbara Barry, Mark Evan Bonds, Reinhold Brinkmann, Berthold Hckner, Klaus-Jrgen Sachs, and Howard Smither for generously sharing with me materials that enriched my understanding of Schumanns life and works. Drs. Mark Allen and Reed Drews provided invaluable insights on the interpretation of Schumanns medical history. I owe my gratitude to other friends and colleagues, including Anna Maria Busse-Berger, Karol Berger, Isabelle Cazeaux, Lewis Lockwood, and Herbert Sprouse, for their sage counsel and unflagging support. To my colleagues at Boston University who have taken a keen interest in this projectCharles Fussell, John Goodman, Phyllis Hoffman, David Hoose, Joy Mclntyre, Emilio Ros-Fbregas, Joel Sheveloff, Roye Wates, Gerald Weale, and Jeremy YudkinI extend a warm thank you, and reserve a special word for my recital partner and friend, Maria Clodes-Jaguaribe, who, like me, is an incurable Schumann lover. As always, the music-library staff at Mugar Memorial LibraryHolly Mockovak, Richard Seymour, and Donald Dennistonresponded promptly and cheerfully to my many (too many) requests.

My thanks also go to the students in a seminar on Schumanns music I conducted in the fall of 1993, especially to JoAnn Koh, Marcus Silvi, and Tom Williams, who reminded me that my hero wasnt victorious in every battle. Many current and former graduate studentsPaul Bempchat, James A. Davis, Simon Keefe, Teresa Neff, Eftychia Papanikolaou, and Elizabeth Seitzlent willing ears to a sometimes obsessed teacher and advisor.

And last, I extend my thanks to the couple whose immeasurable support of my activities extends back forty years: my parents, Margaret and John D. Daverio. I dedicate this book to them, with love.

J. D.

Boston

March 1996

Contents

Robert Schumann

Introduction: Schumann Today

The Biographical Challenge

To write, near the turn to the twenty-first century, a study of the life and works of Robert Schumann is perhaps both presumptuous and foolhardy; presumptuous, because so many studies of the composer already exist; and foolhardy, because biographies, if some of the latest critical punditry is to be believed, may soon become the museum pieces of writerly genres. Among nineteenth-century composers, probably only Beethoven and Wagner might boast of having served more often as the subject of biographical inquiries than Schumann, whose story has been told and retold, revised and corrected, again and again. Moreover, the biographical method itself is under fire; before long, general studies of an artists life and works may well be viewed with the same circumspection among scholarly writings as the historical romance is among literary genres. The guiding ideas of the nineteenth century, after all, can hardly be transplanted uncritically into the twentieth. For most of us, art is no longer the unmediated expression or reflection of the artists inner life. The unity of lived experience and artistic productso dear to nineteenth-century thinkingwas already consigned by Walter Benjamin some three-quarters of a century ago to the realm where it belongs: to myth; fictional heroes, not living subjects, exemplify a perfect synthesis of this sort.

Then why should we have yet another biography of Schumann? In the first place, the project poses an interpretive challenge. The antinomy with which Karl Laux begins his compact but still useful study of Schumanns careerIt is easy to write a Schumann biography [because Schumann wrote it himself]. It is difficult to write a Schumann biography [because the modern biographer must chart the composers relationships to his complicated and contradictory social surroundings]is more than a rhetorical ploy. The difficulties entailed in writing a biography of Schumann are rooted not only in the complexities of the composers world, but also in precisely the wealth of biographical material on which the writer must draw. Thanks to the painstaking editorial efforts of Martin Kreisig, Georg Eismann, Martin Schoppe, and Gerd Nauhaus, scholars have access to the rich fund of materials offered in the diaries and travel notes that Schumann maintained with some regularity from January 1827 to early 1854. Nauhauss edition of the three volumes of

Next page