Music is the most romantic of all the artsone might almost say, the only genuinely romantic onefor its sole subject is the infinite .

E. T. A. HOFFMANN

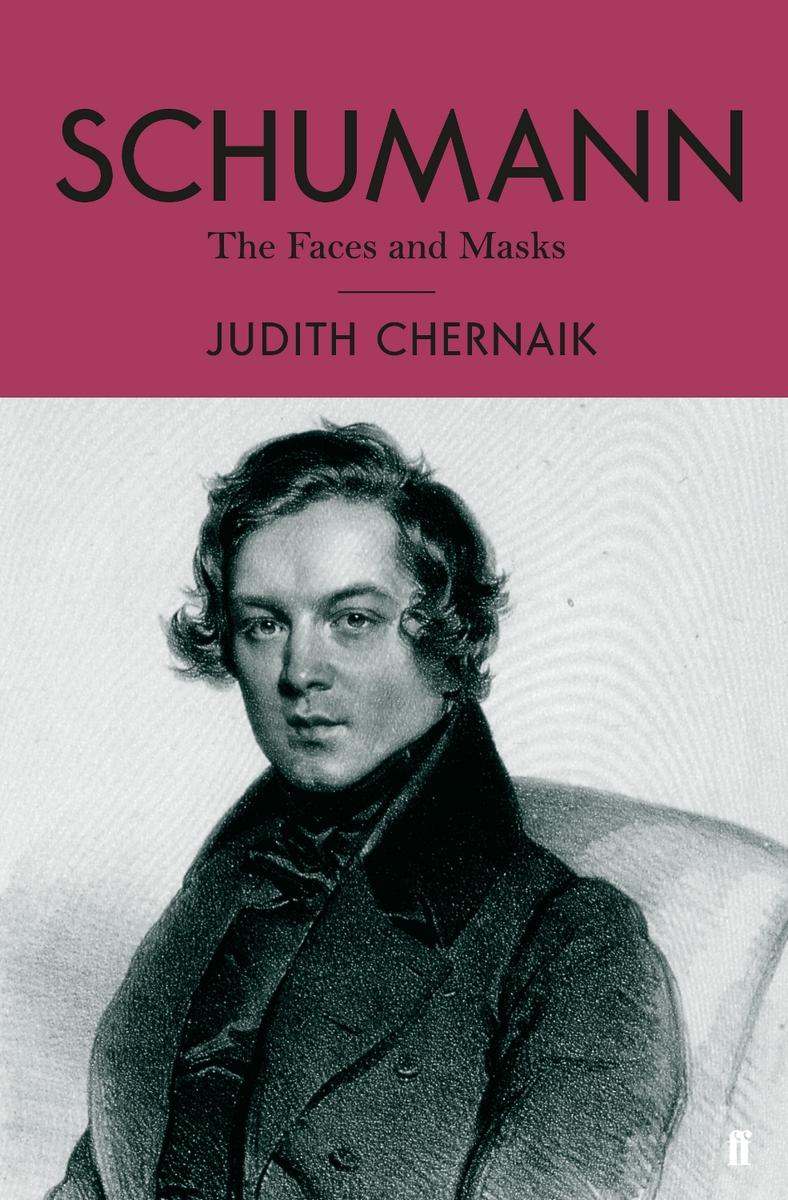

S chumann was a key figure in the new Romanticism of his age. He was a true Romantic in his embrace of poetry and feeling, his love of emotional extremes, his intermingling of life and art. He held passionate convictions about the art of music that was food and drink to his fellow musicians in their youth. He believed that music, like all the arts, must respond to the times, that it must be original and forward-looking while building on the greatest works of the past. His music was closely interwoven with the chief events of his life and the people he loved, especially his wife, Clara, herself a great artist. His major works have endured through all changes of taste up to the present time.

He was the most literary of composers. In his early years he was torn between literature and music and tried his hand at both. Fortunately for us, his early sketches for novels in the style of his favorite Romantic writers came to nothing. Instead we have the enduring magic of Carnaval and Kinderszenen , the great song cycles, a wealth of chamber music, four symphonies, the Manfred Overture, and many other orchestral and choral works. His ambition to become a virtuoso pianist had to be abandoned when he injured his right hand, having used his own ingenious invention to strengthen the weak middle fingers. His extraordinary artistic achievements must be set against recurrent illness, self-inflicted obstacles, and misjudgments, detailed in the following pages.

More than 150 years after his death in Endenich asylum, aged forty-six, Schumanns life and works still arouse partisan debate. Biographers disagree about whether to attribute his final illness to lifelong mental disorder or to the last stage of syphilis, contracted in his early youth. Performers argue about the merits of his late works: the Violin Concerto, which his close friend the violinist Joseph Joachim believed unworthy of publication; a song cycle setting the sentimental poems of a child poet for whom Schumann felt great enthusiasm; the haunting Songs of Dawn for piano, almost the last work he wrote before his breakdown. Some critics think these works reflect his mental decline; others see a master forging new artistic paths.

Questions still rage about Schumanns skill as a symphonist. Brahms and Clara Schumann were bitterly estranged following a quarrel about the respective merits of the first and final versions of Schumanns D Minor Symphony. Gustav Mahler, who championed Schumanns works, reorchestrated the symphonies with a heavy hand. In his performances and recordings of all four symphonies, the conductor George Szell defended them as supreme masterpieces against the opposition of virtually all his colleagues, but he too indulged in some reorchestration. Leonard Bernstein, a great admirer of Schumann, was one of the first conductors to return to Schumanns original scores.

Clara Schumanns role in Schumanns life remains a subject for debate, as her own works are rediscovered and newly assessed. Was she responsible for tempering the originality of Schumanns early works, urging him toward more conventional forms? Was her own genius stifled by Schumanns love of home and family? The complex relationship of these two great artists was central to the work of both, giving definitive shape to Clara Schumanns career and immortalized in Schumanns music.

Described by friends as an impractical dreamer, Schumann founded and edited a successful music journal with contributors in every major European city. No doubt his fathers experience as a publisher, translator, and editor contributed to his own expertise. Like his father, he had to prove his financial competence before marrying the woman he loved. Throughout his life, he carefully noted all professional and household income and expenses, down to the last groschen for beer at his favorite tavern.

His diaries describe bouts of depression, fears, and phobias, anddetails omitted in the early biographieshis sexual experience, his overindulgence in alcohol, his determination to reform, and his frequent lapses. It is possible that he suffered from what is now called a bipolar personality. He records symptoms associated with depression: sleeplessness, racing thoughts, nightmares, inability to work. Yet he was remarkably productive, writing compulsively in periods of intense creative inspiration. He had a high sexual drive, often related to manic excitement. He suffered panic attacks; he feared living on a high floor lest he be tempted to throw himself from the window. He idealized his fellow musicians Chopin and Mendelssohn, and he invested his close friends with qualities larger than life. They became characters in a novel, with literary names and personalities. He fell in love with married women, moved on easily to romantic infatuations with more available women, until his attachment to the young Clara Wieck deepened to become the great love of his life.

Schumanns fantasies entered into his music with the creation of the impetuous Florestan and the sensitive Eusebius, Romantic doubles of Schumann himself. Florestan and Eusebius are credited as the composers of his early works for piano and the authors of articles for his music journal; it is their names or initials, rather than Schumanns, that appear on his published scores and in the journal. They join commedia dellarte clowns in his delightful Carnaval masquerade; they write variations on themes composed by Clara in dances full of wedding thoughts. Many other elements of Schumanns life play significant roles in his music: his vast reading, his liberal political enthusiasms, his love of games and puzzles.

As he assumed many masks in his music, he also had many faces, many selves. He compiled notes for an autobiography at intervals throughout his life, each time stressing selective features of his history. He instinctively presented different aspects of himself to Clara, to Mendelssohn, to close friends and distant acquaintances. His inmost self is revealed in his music, but that self, too, is multifaceted. In his songs Schumann speaks through the words of his favorite poets. In all his music, the real self, the personal signature, is instantly recognizable but extremely resistant to analysis.

This study of Schumanns life and art is addressed primarily to the general reader, the music lover who may have no specialized musical training. I have tried to avoid technical language, but I hope to convey a sense of the quality and range of Schumanns compositions. In his music he expressed everything that he felt unable to express in words. When he was improvising at the piano or writing at his desk, composing his wonderfully original piano suites, inventing musical settings to love poems and ballads, tackling the larger forms of symphony and chamber music, it was his true self that was speaking. His early works are closely related to his own experiences, his moods, his fantasies, his relationship with Clara, both before and after their marriage. His later works also lend themselves to autobiographical readings. They should be read in terms not only of his life but his world, its politics, its ethos, its dominant themes. He gave musical voice to his imagined