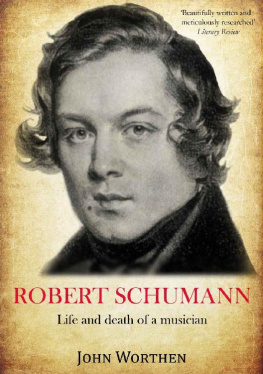

Robert Schumann

Life and Death of a

Musician

John Worthen

All Rights Reserved

Copyright John Worthen 2007

First published 2007 by Yale University Press

This edition published in 2014 by:

Thistle Publishing

36 Great Smith Street

London

SW1P 3BU

www.thistlepublishing.co.uk

For Peter (1938-2002)

Illustrations

.

.

.

CONTENTS

Preface

To question things currently believed without being subjected to further investigation wherever you go, that is the most important thing.

In February 1854, at the age of forty-three, Robert Schumann attempted suicide; in July 1856 he died in an asylum. For writers and musicians since then, mental disturbance in some form has been regarded as central to almost everything he felt and did.

Confronted as I am by the quantities of writing about Schumanns mental problems the innumerable articles proposing yet another solution to what was wrong with him, the assumption by every biographer and every commentator that he was unstable in ways that led to his insanity and death I feel more than a twinge of anxiety at proposing a life story in which such speculation plays little part. The evidence, however, shows that although he suffered episodes of severe anxiety, and at times was both depressed and exhilarated, Schumann is unlikely to have approached a state for which diagnoses like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia or progressively unbalanced or even instability would be appropriate. The problem is that attempted explanations of what happened to him between 1854 and 1856 have been imposed upon his life before 1854; the evidence of what he actually wrote, did and felt, and of how people viewed him, has never sufficiently been attended to. This biography attempts to liberate Schumann from the preconceptions about mental illness which have dominated almost every account of him offered during the past one hundred and fifty years.

PART I

EARLY YEARS

I liked it best to go for walks all by myself...

RS aged fifteen (Burger 32)

Birth and upbringing: Zwickau 18101828

Robert Schumann was a wonderfully ordinary child. That sentence shows him, at the age of only fifteen, finding a disarmingly poetic way of recreating his early years; but if he had not been a musician he would certainly have been a writer.

He was the last-born, so-called handsome child; his contemporaries remembered him as a very handsome young man with blue eyes some said grey.

Born on 8 June 1810, he was the sixth child of his parents, August and Johanne Christiane Schumann.relieved to have given birth at such an age and after the stillbirth of the previous year. Twenty-five years later she recalled in a letter to her son (for a man in his mid-twenties, perhaps a rather embarrassing recollection) how

With tears of joy I pressed you to my breast and heart, for it had been prophesied that giving birth to you would be a hard struggle for me. Your good father was equally speechless and happy, because he too had silently worried about the delivery. So your first breath in this world was a joy to others and your existence painless for you.

Although Robert was the only one in his family who grew up musical, his mother prided herself on the number of operatic arias she could sing by ear.

Kuntsch, although a loving, good man, was only a mediocre talent at the keyboard, as Robert became aware. But he was a striking figure in the community. His father had been an agricultural labourer and Kuntsch formally polite, old-fashioned in his habits and pedantic even in trifles had worked his way up to professional respectability. In provincial Zwickau, totally cut off from the musical world and a place then utterly insignificant, the effect of having a self-made man as a teacher cannot be overestimated. For all the disadvantages of being born to a non-musical family in a non-musical place, Robert grew up believing that he too could overcome any disadvantages arising from his background and be a self-made musician. And to a surprising extent that is what he became.

But literature also attracted him. His fathers library was large; Robert read voraciously and as a child started to write. When he was nine, he and his brother Julius performed robber-plays they had written together, on a stage which their father had built for them. The sons of a shopkeeper, they knew the importance of paying customers: I, my brother and some other schoolfriends had a really nice theatre which however made us well known all around Zwickau, The booksellers child was passionate but also determined to pay his way.

Music however, once having come into Roberts life, grew more and more important. When he was eight, his mother took him with her down to the spa in Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic); they saw there the pianist Ignaz Moscheles, only in his twenties but already famous, and the boy was deeply impressed. All his life he kept a concert programme which the great man had touched. That is almost the only surviving anecdote of his childhood musical achievements. The period it relates to is uncertain; a seven-year old managing such a feat would be wonderful, a seventeen-year old doing so would not be. And there is no way of checking the anecdotes reliability, though its early date is in its favour. What it records is something that mattered enormously from the start: Roberts capacity to improvise at the keyboard.

By the time he reached his teens, Robert had taught himself enough to be playing the piano in the few private houses in Zwickau where good music was appreciated. One was the home of the Schlegel family (where chamber works were frequently performed

Schumann was showing his characteristic tactless determination to go his own way; he was proud, obstinate, determined and hot-headed. As he grew older, these characteristics tended to be disguised by his habitual quietness of manner and speech, so that people who did not know him well assumed that he

An interpretation of Robert Schumanns life of the kind which has up until now dominated biographical writing about him as a life headed, from the start, towards depression and mental illness has to ignore his happy childhood and youth. It naturally stresses other things. When Robert was three, for example, the fear that his mother might have been exposed to typhoid fever led to his being sent to stay for six weeks with the Ruppius family (the mother being his own godmother); he lived with them for the best part of two and a half years. They enjoyed having him and he in turn loved Frau Ruppius; he called her my second mother.

While living away from home, Robert would go and see his own family once a day, but he also remembered not having missed them. By his own account, he was only made miserable by having, in the end, to go home: the night before I left this house, I could not sleep and wept throughout that night... in the morning I was found sleeping while tears rolled down my cheeks. As He grew up loved and admired in both his families.

August Schumann was, however, not a well man, although he struck a family friend as incredibly dedicated to his profession: I never saw him doing anything else than work. for her son. The idea of Robert trying to make his way as a musician horrified her.

Robert certainly found his mother difficult. He singled out his father as the parent he especially loved and as the one who recognised and encouraged his musical talent. But it is hardly a sign of psychological disturbance to prefer one parent to the other. He remained very fond of his mother and for her he was always my bright spot.

For all his fathers delight in his talents, and his own self-taught skills, Robert Schumann was not a musical genius when young; emphatically not a child prodigy. Prodigies are made, not just born; witness the young player Ludwig Schuncke, born in Stuttgart, Roberts six-month-younger contemporary (and Apart from the Schlegels, the Caruses, Kuntsch and his father, neither his home nor his town took much interest in music.

Next page