Dawid Sierakowiak - The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto

Here you can read online Dawid Sierakowiak - The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2008, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2008

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Dawid Sierakowiak

from the

Lodz Ghetto

edited and with an introduction by

Alan Adelson

translated from the Polish original by Kamil Turowski

foreword by Lawrence L. Langer

-Czeslaw Milosz

Warsaw, 1943

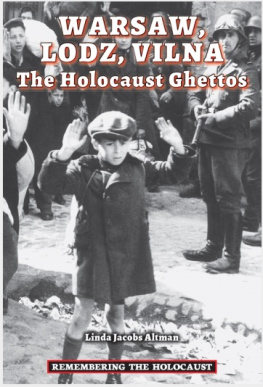

If a primary task of Holocaust literature is to help us imagine the ordeal of those who struggled to stay alive in ghettos and camps, then Dawid Sierakowiak's Diary must be hailed as one of the leading texts in the canon. Unlike Anne Frank's Diary, with which it is sure to be compared, Sierakowiak's record of diminishing existence in the Lodz Ghetto draws us into the landscape of a savage and incessant oppression from which the young girl hiding in an attic in Amsterdam was lucky enough to be shielded. Although their eventual ends were the same-to die in misery-their routes diverged, and one can only hope that readers will greet Dawid Sierakowiak's sober impressions of Jewish life under the Germans with the same acclaim they gave Anne's Diary. It is a milieu Anne herself would grow acquainted with only after she no longer had a chance to write about it.

Dawid's Diary begins on June 28, 1939, a few weeks before his fifteenth birthday, and breaks off on April 15, 1943, a few months before he would turn nineteen. He died on August 18 of that year, apparently from tuberculosis. The remaining inhabitants of the Lodz Ghetto, including his younger sister, would have to endure hunger and disease and the illusion of rescue until August 1944, when most of them were deported to Auschwitz. Few returned.

Although there are a few gaps in Dawid Sierakowiak's account because notebooks have been lost, we nonetheless gain from his surviving daily entries a vivid sense of how his own and his community's fate was slowly replaced by its doom. As control of their lives shifted from themselves to the Germans, the future ceased to mean what you might be or do and became instead an issue of how soon you would die. The brutal agents of this doom, the Germans who willfully ignored sanitary conditions in the ghetto and allowed infectious diseases like typhus and tuberculosis, together with hunger, to claim increasing numbers of victims, remain offstage in this drama of a people's gradual slide into the pit of death. The same irony that pervades many Holocaust testimonies and memoirs infiltrates Dawid's text too-the real criminals virtually disappear, and their prey seem to bear the burden of guilt for their own destruction.

This remains one of the most vexing moral dilemmas for Holocaust commentators, and the young Dawid confronts the problem with a mixture of resentment and dismay. As he watches his own family and his neighbors waste away, he is increasingly piqued by the hierarchy of privilege that prevails among Jews in the ghetto. Ghetto head Chaim Rumkowski and his aides, members of the Jewish police, doctors, instructors in the workshops where "ordinary" Jews were employedthose Primo Levi would label the "Prominenten" in a place like Auschwitz-were favored with better living conditions and adequate rations, while the rest of the population fought to stay alive on meager food in sparsely furnished quarters. This inequality of opportunity never ceased to offend the young Dawid, whose political sympathies lay with the Marxist philosophy of the Soviet Union.

Just as readers of Anne Frank's Diary, in order to appreciate her full ordeal, must be familiar with the journey of the Frank family to Westerbork, Auschwitz, and Bergen-Belsen after they were arrested, so readers of Dawid Sierakowiak's Diary must know the context of his entries in order to respond to their sinister resonance. As the Germans begin to deport those unfit for work, the diarist innocently muses, "Nobody knows what the Germans do with the children and those unable to work." Large numbers of Jews begin to arrive in Lodz from Vienna, Prague, and the Czech Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. They are not absorbed into the labor force in the ghetto, but are shipped to work camps in the area of Poznan, according to Dawid. We know that they are being sent to Chelmno, where they are murdered in mobile gas vans and buried in mass graves. But when the deportations temporarily cease, Dawid solemnly complains, "Even that chance for getting out of the ghetto has been taken away." By drying up usual sources of information, the Germans found it easy to avoid rousing the suspicions of their victims.

Later, when the Germans reduce the size of the ghetto population (and hence the mouths that need to be fed) by sending off the aged, the ill, and all children younger than ten, illusions begin to fade: "although Rumkowski assures us that he guarantees 'safe conduct' for these children, no one really believes him," Sierakowiak asserts. Parents do what they can to hide their offspring, but the Germans are ruthless and thorough, and few escape. Rumkowski's strategy is to save those he can by surrendering the rest; the text of Dawid's Diary makes clear how much anguish he caused for others by his megalomaniacal self-deception.

Some readers may wonder why there was no uprising in Lbdz comparable to the one in the Warsaw Ghetto. Dawid's daily observa tions help us to understand why. By April 1943, the time of the Warsaw rebellion, it was clear that the Germans had decided to liquidate that ghetto and deport its remaining inhabitants. Those involved in the insurrection knew about Treblinka and had no illusions about their fate, But in L6dz, Rumkowski was opening more and more workshops, and Jews lucky enough to be employed in them had some grounds for believing that their labor was of sufficient value to the Third Reich to ensure their survival at least until war's end. Hence, to protect a "safe" future, Rumkowski was determined to stamp out any sign of internal dissent. Moreover, even a stunted hope is a powerful antidote to the "nobility" of collective suicide.

Dawid Sierakowiak himself was a creature of alternating moods. From time to time, rumors spread through the ghetto of various Allied initiatives, and the Jews of Lodz soaked them up like sponges. Such rumors became the lifeblood of a forsaken population, especially as living conditions grew harsher and harsher. Dawid reports them faithfully. But by the time the fourth year of the war arrived, on September 1, 1942, the diarist had little hope that anyone would stay alive to the end, whichever side won. His litany of sorrows reveals a mind resolved to unveil the true plight of his community: "Day after day passes. One buys rations, eats the little food there is in them, starves while eating it, and after that keeps waiting obstinately, continuously and unshakenly until the end of the cursed, devilish war.... We're fighting to survive until liberation, a goal as elusive as a phantom."

Those hoping to find in this diary a tribute to the invincible human spirit are bound to be disappointed. Indeed, one of its distinct merits is to convey how powerful a role something as mundane as "40 [dekagrams] of sugar, and 20 [dekagrams] of margarine" could play in the drama of death by starvation unfolding relentlessly in its pages. Dawid is staggered one day by the news that a former neighbor, "an absolute athlete before the war," has died of hunger: "His iron body did not suffer from any disease; it just grew thinner and thinner every day, and finally he fell asleep, not to wake again." Among the many crimes committed by the Germans in the Lodz Ghetto and elsewhere is this: they blithely divorced their victims' deaths from the manner of their lives, leaving a legacy of disrupted achievement that neither logic nor memory can ever reconcile.

For no one is this more true than for Dawid Sierakowiak himself, a talented young man who, had he survived, might have parlayed his intellectual gifts into a promising literary career. He mastered several languages, reading, as he tells us, Galsworthy in English, Thomas Mann's Buddenbrooks in the original, the plays of Ibsen and Strindberg in German translation, Romain Rolland in Yiddish, while inaugurating the vocation of author by writing poems and essays in Polish and Yiddish. Not too long before his death, he even began translating one of Lenin's works into Yiddish. But he has few illusions about the ultimate value of these endeavors, inscribing his forays into Schopenhauer with a wry if melancholy wit: "Philosophy and hunger: quite a combination."

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto»

Look at similar books to The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.