Copyright 2022 by Tyler Dunne

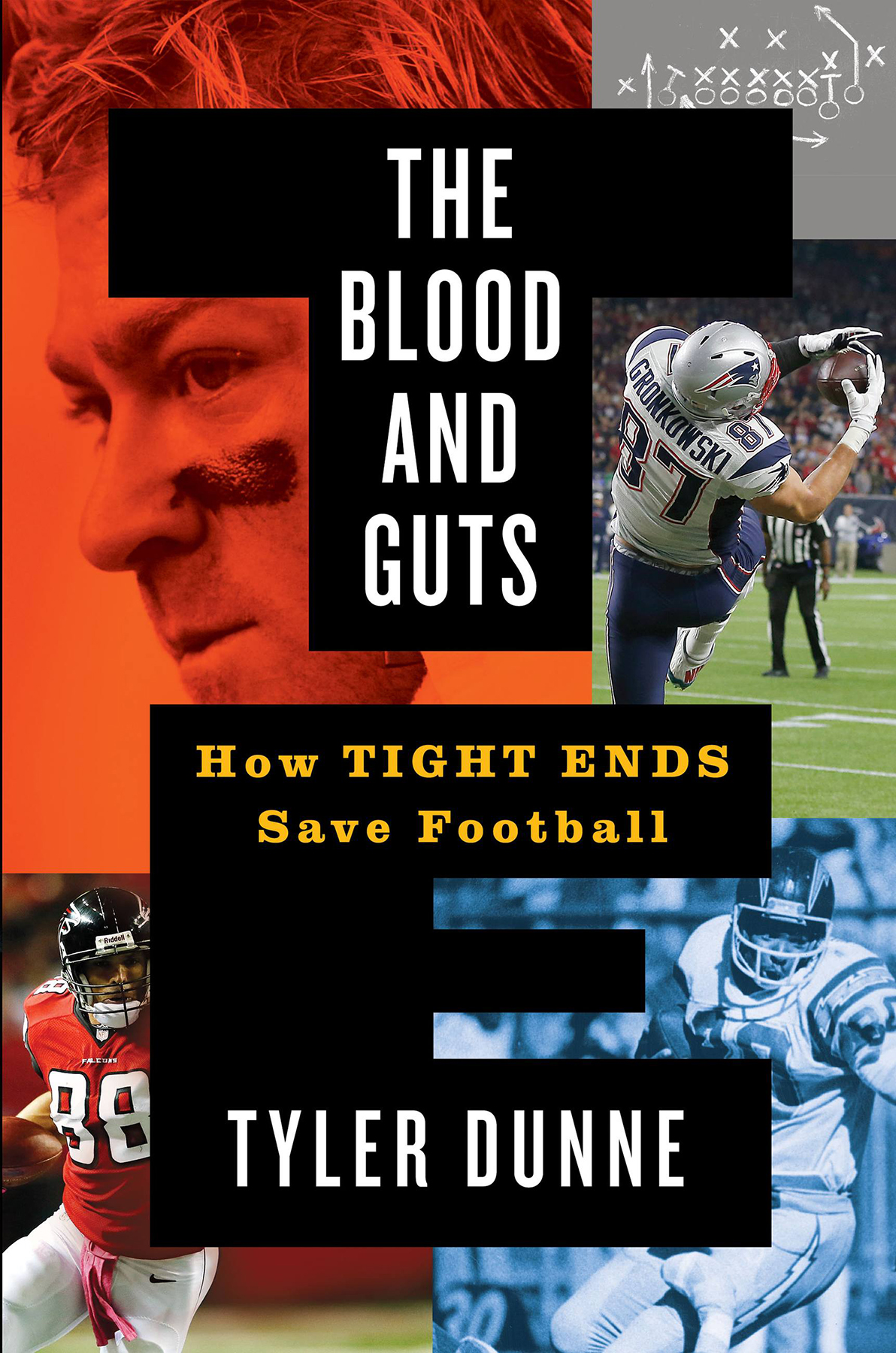

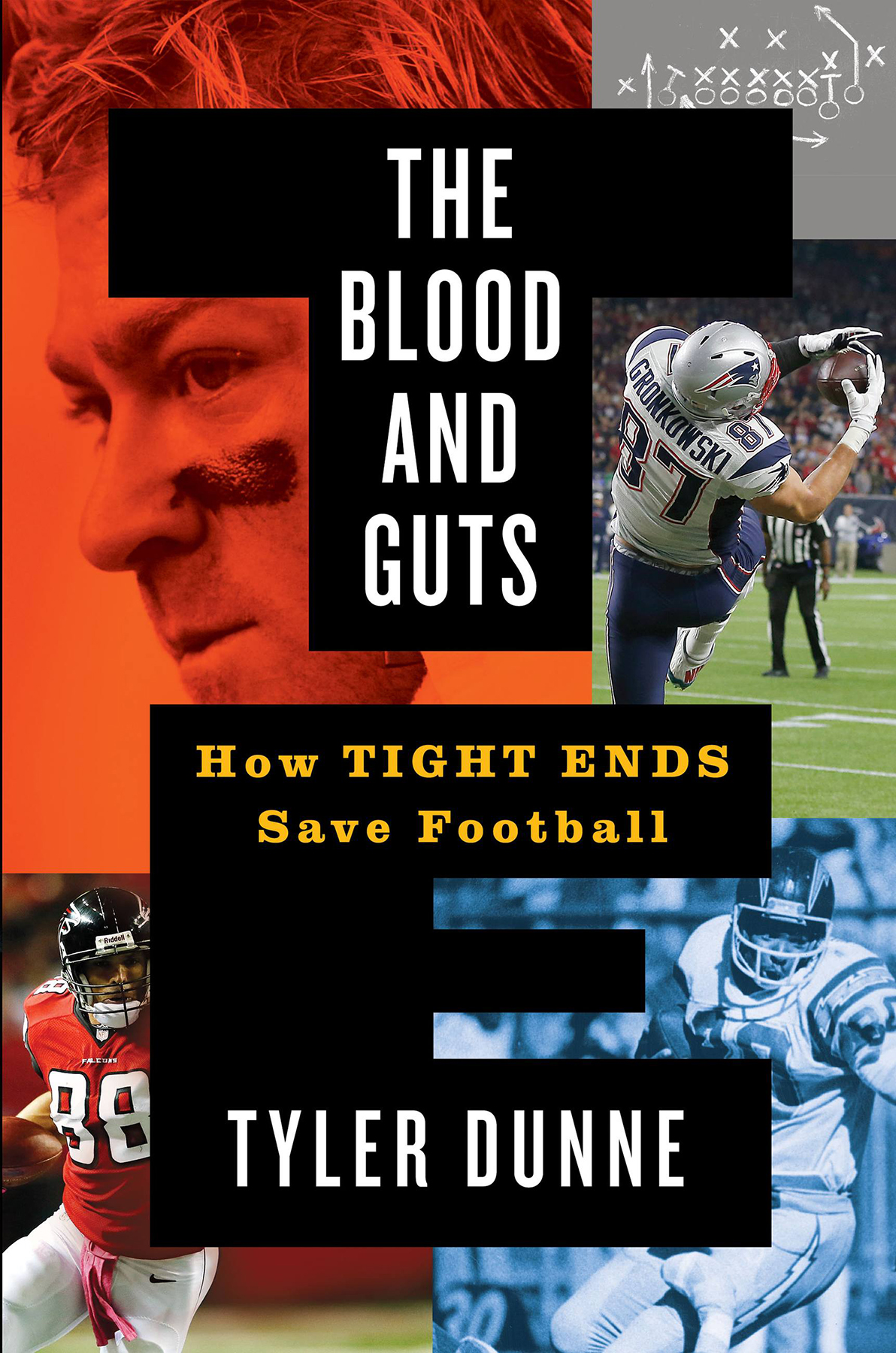

Cover design by Henry Sene Yee

Cover top left image by Al Messerschmidt/Getty Images, top right image by Bob Levey/Getty Images, bottom left image by Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images, bottom right image by Denver Post/Getty Images

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Twelve

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

twelvebooks.com

twitter.com/twelvebooks

First Edition: October 2022

Twelve is an imprint of Grand Central Publishing. The Twelve name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dunne, Tyler, author.

Title: The blood and guts : how tight ends save football / Tyler Dunne.

Description: First edition | New York, N.Y. : Twelve, Hachette Book Group, 2022.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022019462 | ISBN 9781538723746 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781538723760 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Tight ends (Football) | FootballOffense.

Classification: LCC GV951.25 .D96 2022 | DDC 796.332/2dc23/eng/20220630

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022019462

ISBN: 9781538723746 (hardcover), 9781538723760 (ebook)

E3-20220907-JV-NF-ORI

For Mom and Dad, who love and support and inspire beyond comprehension

The absurdity of the profession becomes clear to players once theyre ejected into mainstream society.

As a player in the National Football League, you are contractually obligated to physically punish your coworkers. You strap on a helmet and take the field with bad intentions. The temperature will rise into the nineties during training camp, too, with livelihoods at stake every rep of every drill. That pales in comparison to your internal temp, of course, because the window of opportunity is small. With an endless supply of potential replacements, one mistake can quickly get you fired in this testosterone-fueled environment.

As coworkers beat the hell out of each other, tempers reach a breaking point. Fists are thrown. Helmets are pulled. Manhood is tested. And, moments later, those same two combatants are seated next to each other in a meeting watching film and talking Xs and Os. No, this is not the scene at your local bank or neighborhood pharmacy. Imagine walking down the hallway at your job, picking up that brownnoser in sales by the collar and piledriving him into a desk, then walking back to your office and running more accounting numbers. It takes a special kind of person to play professional football and, by God, its beautiful. This is as close as we have to modern-day gladiators.

No sport captivates America like football because football is the most primitive form of competition in human existence. And no position captures the essence of this all quite like the NFL tight end.

Remember Jeremy Shockey showing zero regard for human life in an exhibition game? Remember the night Jason Witten was sandwiched by two Philadelphia Eagles defenders, his helmet popped off, and he kept running? And Travis Kelces walk-off touchdown in the playoffs? And Rob Gronkowski throwing Sergio Brown out of the club? And John Mackey treating the Detroit Lions defense as a collection of bowling pins? This is the book for you.

As the men playing this sport get stronger and faster, the league has tried to curtail injuries. Rules overcorrect over time. Controversy threatens the leagues brand just about every year. Yet the NFL plows through it all because what drew everyone to football to begin withthe violence, the fact that this sport is not for everyoneremains. Anyone can play a game of H-O-R-S-E in the driveway or gather at the neighborhood park for a baseball game. This requires something different from the pit of your stomach.

The tight end is the sport itself distilled to one position. You must possess the athleticism to burn a 190-pound defensive back downfield one play, the guts to stick your face into the chest of a 300-pound defensive end the next, and the toughness to wipe that blood away and play on. Brawn alone is not enough at tight end, either. Youre required to tap into corners of your brain other players never do. The NFL can try to sanitize its product year to year, rule to rule. Everything we love about football will always be saved at the position Mike Ditka essentially founded sixty-plus years ago.

I traveled all over the country to get inside the minds of the players defining the sport you love. My hope is that The Blood and Guts veers a magnifying glass over the individuals who were uniquely qualified to ensure football is forever football. Maybe all that yellow laundry on the field has you ready to hurl your remote control directly through the television set. Rest assured. The sport will never become too soft for its own good thanks to the tight end.

Down in Miami, I throw back drinks with Shockey, a man who brought the sport back to its eye-for-an-eye roots. In St. Louis, Jackie Smith relives a football life that took him to the highest of highs and lowest of lows. He proved just how powerful the mind can be in this sport. In Austin, Tony Gonzalez soul-searches for hours. Hes the one who forced the league to reimagine this positions endless possibilities. As that revolutionary force, Gonzalez made friends and enemies and, above all, discovered exactly how playing tight end makes you a better person. The lessons Gonzalez learned are now being passed down to his kids. Same goes for Dallas Clark, a tight end miracle whos a direct product of his hardships. He lost his mother. He walked on at Iowa. He transformed from a walk-on mowing the grass at Kinnick Stadium to catching third-down passes in the playoffs from Peyton Manning. It wasnt an accident.

In North Carolina, Ben Coates struggles to walk around his house. He sacrificed his body and never thought twice about it. Hed do it all over again, too. No way did Jimmy Graham imagine a life in pro football when he feared for his life inside a group home. Now? Hes a source of hope for both orphans and, of course, any basketball player trying to cross over to this ruthless sport.

Rob Gronkowski lived like theres no tomorrow, pounding booze and popping his top and ejecting defensive backs into another dimension. George Kittle turned moving another man against his will into a lifestyle. Together, theyve driven the tight end into the next generation.

And down at his golf course, I kicked back with the man who started it all. Its hard to imagine where the sport would be without Mike Ditka. He grasped the cutthroat reality of the sport. Be it conscious or unconscious, tight ends forever take their cue from Iron Mike.

Maybe nobody could possibly relate to the nine-to-five that is professional football, but theres no need to panic. Its being preserved.

A funny thing happened the more I chatted with these tight ends, too. The tight end position doesnt only show us everything we need to know about football. It teaches us about life.