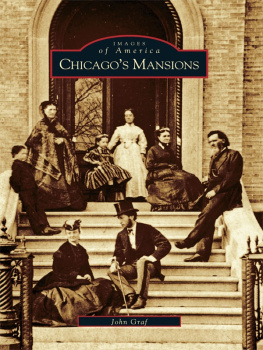

IMAGES

of America

PITTSBURGHS

MANSIONS

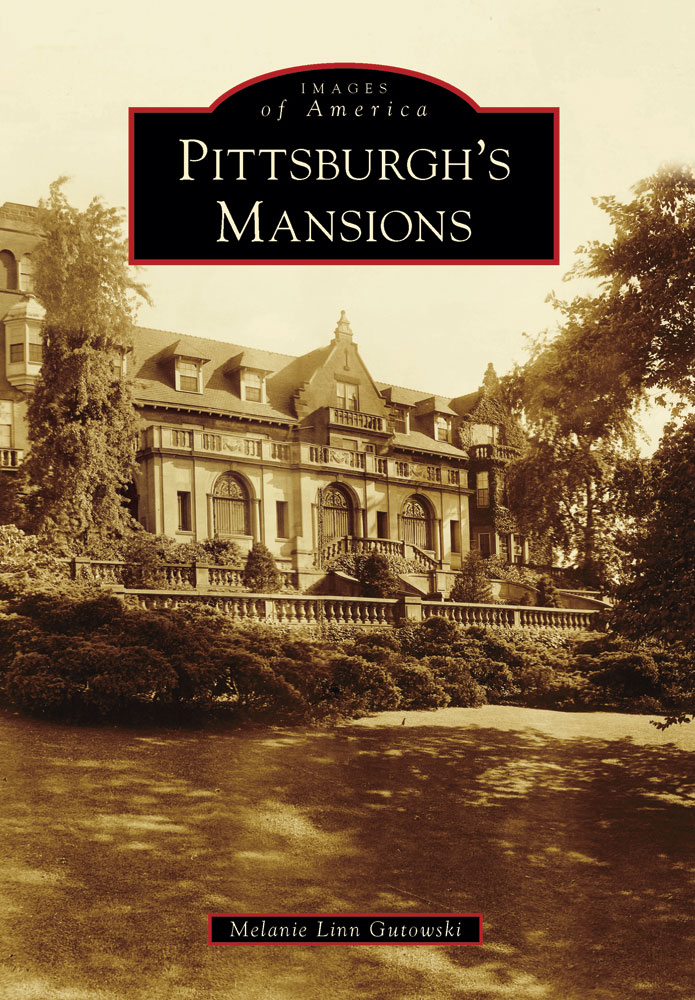

ON THE COVER: Lyndhurst was built by William Thaw Sr. in 1888. The home stood on a nine-acre plot of land at Fifth Avenue and Beechwood Boulevard in Point Breeze. It was demolished in the 1940s. (Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.)

IMAGES

of America

PITTSBURGHS

MANSIONS

Melanie Linn Gutowski

Copyright 2013 by Melanie Linn Gutowski

ISBN 978-1-4671-2015-9

Ebook ISBN 9781439642474

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013931868

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Mom, for sparking my lifelong interest in old houses and in reading about them; and to Dad, for all that early writing practice.

CONTENTS

As a lifelong devotee of old houses, I consider this book very much a labor of love, though not one I could have completed alone. I am deeply indebted to an excellent group of archivists and librarians, including Martin Aurand, Carnegie Mellon University Libraries; Art Louderback, Heinz History Center Archives; Julie Ludwig, Frick Art Reference Library; Miriam Meislik, University of Pittsburgh Archives Service Center; Rachel Grove Rohrbaugh, Chatham University Archives; and Albert Tannler, Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

Thanks also go to Frank and Maura Brown, Jack Carpenter, Charlotte Cohen, Mary Del Brady and Richard Pearson, Al Mann, and the East Liberty Valley Historical Society for sharing stories and images.

I would not have had the wherewithal to complete this project without the unending support (and patience) of my husband, Marc; my parents; and other friends and family members, especially my aunts. An honorable mention goes to Mommys little research assistant, who, though not much actual help, did chime in frequently with kicks of encouragement.

The bulk of the images in this volume appear courtesy of Carnegie Mellon University Libraries (CMU), Chatham University Archives (Chatham), and Senator John Heinz History Center, Library & Archives Division (HHC). Images from other institutions and/or individuals are credited as such. All uncredited images appear courtesy of the authors collection.

A mans home is his castle.

English aphorism

It is said, though difficult to verify, that during Pittsburghs peak yearsroughly 1830 to 1930the city had more millionaires than New York City. Western Pennsylvania had long been a manufacturing center, first of glass, then iron, and then coal, oil, and steel. At that time, local industry was enabling the building of the world, which in turn enabled many men who profited from this fact to build their own world, largely cosseted away from the very evidence of their business success. Wealthy neighborhoodsat the time considered suburbsbegan to emerge in the citys East End and in neighboring Allegheny City. The sprawl of affluence continued into areas that today are considered the citys suburbs and into the countryside. Immense homes with scores of rooms, sometimes nearly 100, soon lined the streets of the city and its surrounding region.

The ready availability of inexpensive household help and low heating costs enabled owners to build larger and ever more extravagant mansions. At the same time, the popular idea of making ones home a sanctuary led to an increasing effort to place more space between oneself and ones neighbors, and especially between the family home and the threatsreal or perceivedof pollution, poverty, and crime.

George Gall, author of Homes and Country Estates of Pittsburgh Men, published in 1905, noted that Pittsburgh did not enjoy the fame for beauty that other cities, such as Cleveland, Buffalo, Boston, New York, and St. Paul, did at the time. Yet in order to demonstrate that Pittsburgh men have been successful in building up as beautiful a city as it is prosperous, one has only to show what has been accomplished in residence building here, Gall wrote. Pittsburghs best residence section is not confined to any one locality or street. This has been brought about by the beautiful and varied topography as seen in the many high elevations and numerous valleys, stretching out in all directions. Her representative people have taken advantage of these natural building localities and erected thereon their homes, in most cases away from the manufacturing districts, where they may obtain rest and quiet after spending many hours amid the noise and din of this great manufacturing and commercial center. As they have selected these naturally beautiful and quiet retreats, so have they in most cases tried to build, selecting mostly, as represented in later work, a style of architecture adapted to the site selected.

While individual prosperity made these homes financially possible, it was a small army of architects that brought the whims and fantasies of the citys industrialists to life. Alden & Harlow, Janssen & Abbott, MacClure & Spahr, and Rutan & Russell are just a few of the partnerships that were active in the area at this period. Individuals such as Louis Stevens, Frederick J. Osterling, Paul W. Irwin, George Orth, and Olaf M. Topp were in high demand among Pittsburghs millionaires, who no doubt traded architect recommendations over Scotch at their private clubs. Gall noted that many of the architects and landscape designers who created these homes had made their own homes in Pittsburgh, a further recommendation of the areas architectural pedigree.

It must be noted that the people represented in this book are overwhelmingly white, male, Anglo-Saxon Protestants. The few women represented herein are generally wealthy widows of these men. Pittsburgh societyindeed, upper-class society as a whole at the timewas not welcoming of Eastern and Southern European immigrants, to say nothing of African Americans, Roman Catholics, Jews, or women.

Many of the homes within these pages no longer exist. While specific reasons vary from family to family, in general, the destruction followed a pattern. Often, the homes original owner would decide to relocate, either to a country home or to another major metropolitan area, such as Boston, New York City, or Washington, DC. The home left behind in Pittsburgh would be sold or left to heirs, who eventually either decided to relocate themselves or could no longer afford to keep the home.

Sometimes, these homes would be donated to the city of Pittsburgh in the hopes that officials would make good public use of the building and its surrounding land. But, the city was in no better position to afford the upkeep of these massive homes than were their former owners, and the houses were often demolished and the land put to other use. It was in this manner that several of the citys public parks came into being. Some owners did look ahead with an eye toward preservation, usually donating their properties to educational or other civic institutions that could not afford to construct their own buildings. If these magnificent homes survived the 1940s to 1960s, when Victorian and Edwardian designs were decidedly out of fashion, the chances were good that they would catch the wave of historic preservation activism brought on by nostalgia, and so remain intact.

Though the people named in these pages are deceased and many of their homes gone, their legacies live on in the names of neighborhoods, streets, schools, parks, and other community institutions. While this book is by no means a definitive catalog of western Pennsylvanias stately homes, the history of Pittsburghs mansions is also a history of the building of the city itself.

Next page