IMAGES

of America

LOST LITTLE ROCK

Hamiltons Drug Store at Fifth and Main Streets is a testament to two things long lost from Little Rocks Main Street: independent pharmacies once common before the rise of chain stores, and the handsome soda fountains found in these establishments, like the one shown here in 1911. White-uniformed employees wait to serve up a milk shake or other treat. Across the aisle is a large display of cigars and a brass spittoon, and a young lady stands nearby holding her parasol. (Authors collection.)

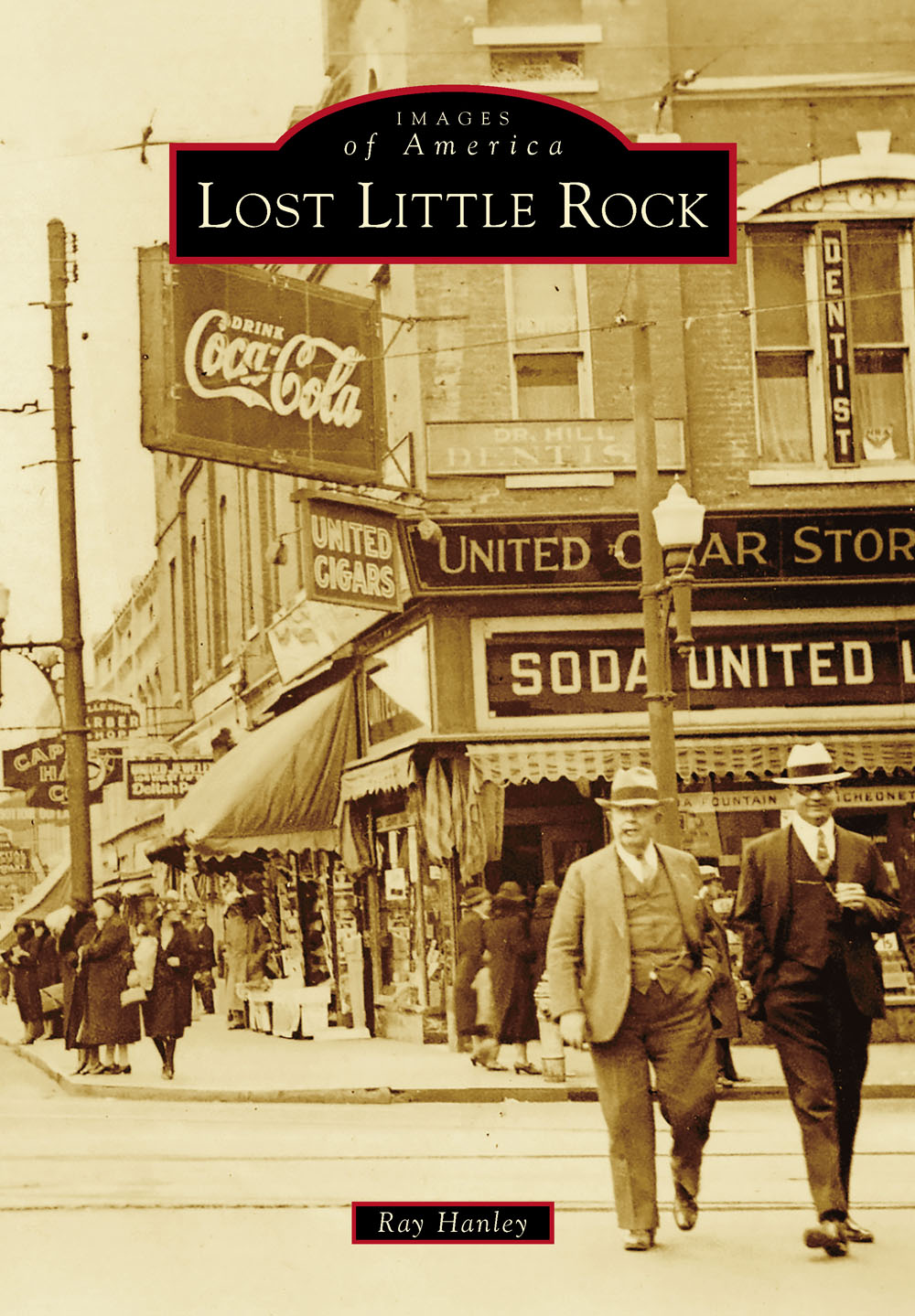

ON THE COVER: At the crossroads of Arkansas, the intersection of Capitol Avenue and Main Street, two men are seen crossing. Today, everything on the right is gone, replaced by a large parking lot and modern office buildings a block down. (Courtesy of UALR Center for Arkansas History & Culture.)

IMAGES

of America

LOST LITTLE ROCK

Ray Hanley

Copyright 2015 by Ray Hanley

ISBN 978-1-4671-1394-6

Ebook ISBN 9781439651797

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014955048

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To all the leaders, both public servants and many in the private sector, who are investing time and a great deal of money in saving and restoring significant Little Rock landmarks.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are owed to Lydia Rollins at Arcadia Publishing, for seeing the merit in this project and for making the decision to put it into print, and to Julia Simpson at Arcadia, for editing and other help. Locally, special thanks go to Brian Robertson at the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies for helping provide some wonderful photographs and for looking up a number of addresses from his trove of city directories; to Kaye Lungren at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture for her help with a dozen wonderful photographs; to Joe Fox of Community Bakery for some vintage images of south Main; and, lastly, to my wife, Diane Hanley, for editing assistance. Unless otherwise credited, all images are from the authors collection.

Little symbolizes the lost past of Little Rock more than the former crossroads of Arkansas, the intersection of Capitol and Main Streets. This photograph, taken at the time of World War I, looks north up Main Street through the busy intersection. Automobiles have begun to crowd out horse-drawn vehicles. The entire block just past the buggy is today a large parking lot. The towering Masonic temple on the right fell victim to fire within a few years.

INTRODUCTION

You dont stumble upon your heritage. Its there, just waiting to be explored and shared. So said Robbie Robertson, a Canadian songwriter credited with penning the lyrics to The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. The quote seems fitting for the subject of this book, Lost Little Rock. The capital city of Arkansas, a rural Southern state, began the first decade of the last century with a robust, architecturally diverse city center filled with wonderful buildings and iconic businesses created by self-made men, often of German and Jewish heritage.

Lost Little Rock seeks to showcase the history of the city center as it was a century ago and to share why so much of what could have been the heritage for the modern citizens of the city has been lost. Because of fires and, especially, repeated decisions to tear down wonderful buildings, it is only through illustrated books like this one that the heritage can be explored and shared. At the same time, the reader will find a few examples of restored and repurposed buildings saved from the wreckers ball to inspire what is possible.

The streets of Little Rock began to be laid out in a grid pattern not long after Arkansas gained territorial status in 1820. Advancing from the Arkansas River, near the literal little rock for which the city was named, commerce crept up Markham and Main Streets. The population reached 700 by 1830, and the key business streets were lengthened to accommodate commercial growth.

By 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, the city was still a collection of mostly one- and two-story frame structures lining dusty (or muddy) Main and Markham Streets. Commercial business still extended only to about Third and Main Streets. The Civil War would slow progress of the developing city, but a bright future waited.

The 1870s saw the population grow, in part from Northerners who had seen the state and its potential during the war. Brick buildings begin to rise, most at least four stories, including the building on Markham Street known today as the states only five-star hotel, the Capitol. By the 1880s, the streets were being paved, and the railroads brought in merchandise and building materials, while business grew south on Main Street and east on Markham Street.

By the 1880s, iconic retailers like Gus Blass were making Main Street a shopping mecca, not only for Little Rock residents but for those from surrounding communities who had easy passenger train access to the growing capital city.

By 1900, Little Rock, with a population of 37,000, was by far the largest city in the state, solidifying its position as the center of retailing, banking, and government. Fires were claiming older wooden buildings on Main Street, affording the chance to rebuild under the direction of leading architects like George Mann, who would design a new state capitol building. Soon, an unbroken line of handsome buildings housing upscale merchants, hardware stores, pharmacies, music stores and bookstores, and lawyers and doctors offices stretched for a dozen blocks south on Main Street from the intersection at Markham Street. Just beyond that point began what is today the Quapaw Quarter historic district, where fine homes arose, fueled by the profits from the prosperous Little Rock business district. At the same time, Markham Street was seeing the rise of hotels and restaurants and to the east a booming area of warehouses, stables, and wholesalers.

By 1920, the buildings were larger on Main Street, and new commerce had opened on Capitol Avenue (Fifth Street). Streetcars rumbled off Main Street a dozen blocks up to the new state capitol, which rose on a hill where a Civil War prison once stood. The most significant architecture was the new Blass Department Store building on the 400 block and the remodeled Rose Building, which sported a neoclassical terra-cotta facade imported from Italy. It was in this era that the window shopper concept dawned on retailers and contractors; both groups profited from remodeling, expanding, and lighting the front windows of Main Street businesses. Merchants believed the more attractive arrangement of merchandise would lead the public to stop, look, and buy. A trip downtown became a great adventure for families.

The Great Depression and World War II deterred the growth of both business and population in Little Rock, but recovery was rapid after the war, when the economy boomed across the nation. Downtown streets were crowded with cars and people at a time when highways began to open up and the first suburbs started to rise. Developments like Broadmoor and Oak Forest afforded returning GIs the ability to buy small tract homes for a few thousand dollars with easy financing. Change was coming for the historic central district of Little Rock in ways that few imagined.

Next page