Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

For Frances

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

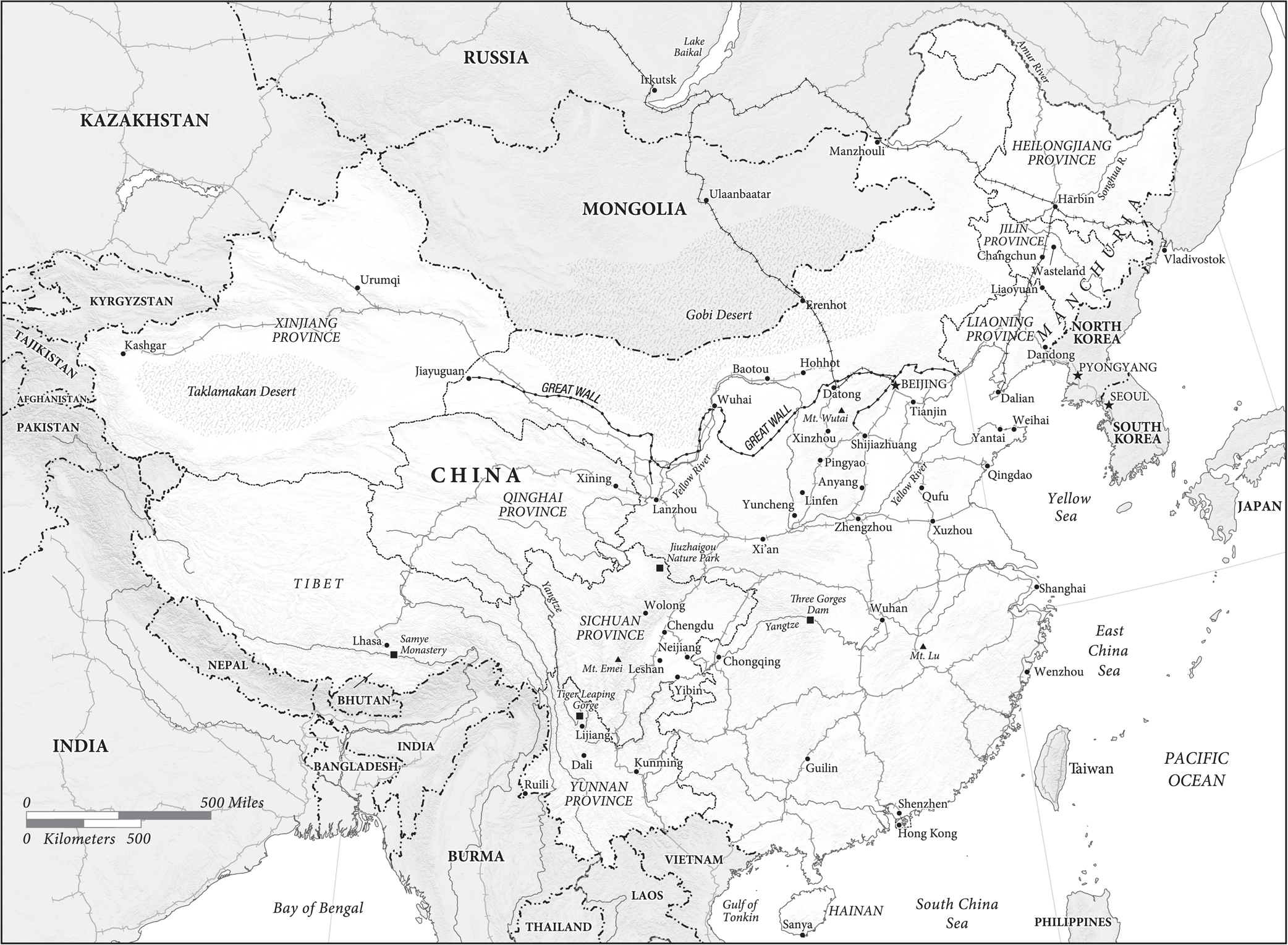

In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China

The Last Days of Old Beijing: Life in the Vanishing Backstreets of a City Transformed

CONTENTS

It is nothing to start a journey, but its hard to end one.

From the classic Chinese novel A Journey to the West

Sometimes to see a place clearly you first have to leave. This is my third book set in China, and the second written while living, on separate occasions, in London, where history is always close at hand. The shelves of Charing Cross Road bookstores sag with guidebooks covering the capitals food, art, architecture, statues, shops, tea, writers, war, buses, churches, jewels, Jews, flowers, ghosts, and secret open spaces. The longer you stay in London, the more you realize how little of it youve seendespite the fact that in 1666, most of the city burned down.

Chinese cities are different: the longer I lived there, the more aware I became of what I could never see, because in China progress often looks like destruction. In London you can drink a pint at the Thames-side pub where Samuel Pepys watched the Great Fire. In Beijing, it is surprising to find your favorite dumpling restaurant still standing after one year has passed, let alone 350.

Unlike The Last Days of Old Beijing and In Manchuria , this is not a book of reportage but rather of mostly chronological impressions, of lessons learned over time. Although my understanding of China has deepened over twenty years, I cant pretend to be a foreign expert, as my work permit alleged. I did not fall in love with China at first sight; the place bewildered me. I arrived knowing very little about the country and unable to speak a word of its language. In this, I resembled the students, job seekers, and travelers who write me asking how best to study Chinese and how to learn China.

I was given advice there, constantly. In the West you greet someone by asking how he or she is doing; in China you begin by informing the person what they should be doing: eating more, paying less, dressing warmer, getting married, or taking a different path and living free and far from the dust of the normal world. A man holding a clucking chicken advised me to do that, moments after I had boarded a public bus in rural Sichuan.

Partings were equally instructive: people sending me off customarily said, Mn mn zu . Go slowly. When food arrived I heard, Mn mn ch. Eat slowly. While studying a map, admiring old photos, or wandering a temple, I was told, Mn mn kn . Look slowly.

Go slowly, eat slowly, look slowly. Often the people suggesting this were themselves in an enormous hurry. The faster China accelerated, the more urgent the mantra became.

I repeat the phrase now because it is also encouraging, in the middle of a long journey, to pause and consider how far you have come.

Spring 2017

I am an unlikely answer to the question, asked anxiously by a Chinese writer in 1935: Who will be Chinas interpreters? Sixty years later I arrived by accident, after rejecting six other countries from the Peace Corps. I was fluent in Spanish, and applied after a short stint volunteering at the Texas-Mexico border with the United Farm Workers, hoping to be sent to Latin America. The Peace Corps offered Turkmenistan, Vladivostok, Sri Lanka, and Kiribati. Its not Club Med, its the Peace Corps, the recruiter finally snapped, after I declined to spend two years in Mongolia or Malawi. You dont get to choose.

Months passed, until one late-spring day the phone rang in the English classroom in Madison, Wisconsin, where I was student teaching. My turf-warring Comp Ed ninth graders had been ordered to attend an assembly optimistically titled Were All in the Same Gang. I warily picked up the receiver, expecting the vice principal to yell that the students in the local branch of the Gangster Disciples were rejecting the suggestion. Instead, I heard the voice of the all-but-forgotten recruiter, who pronounced a single word with great finality: China . It sounded like a sentence, although really it was a reprieve.

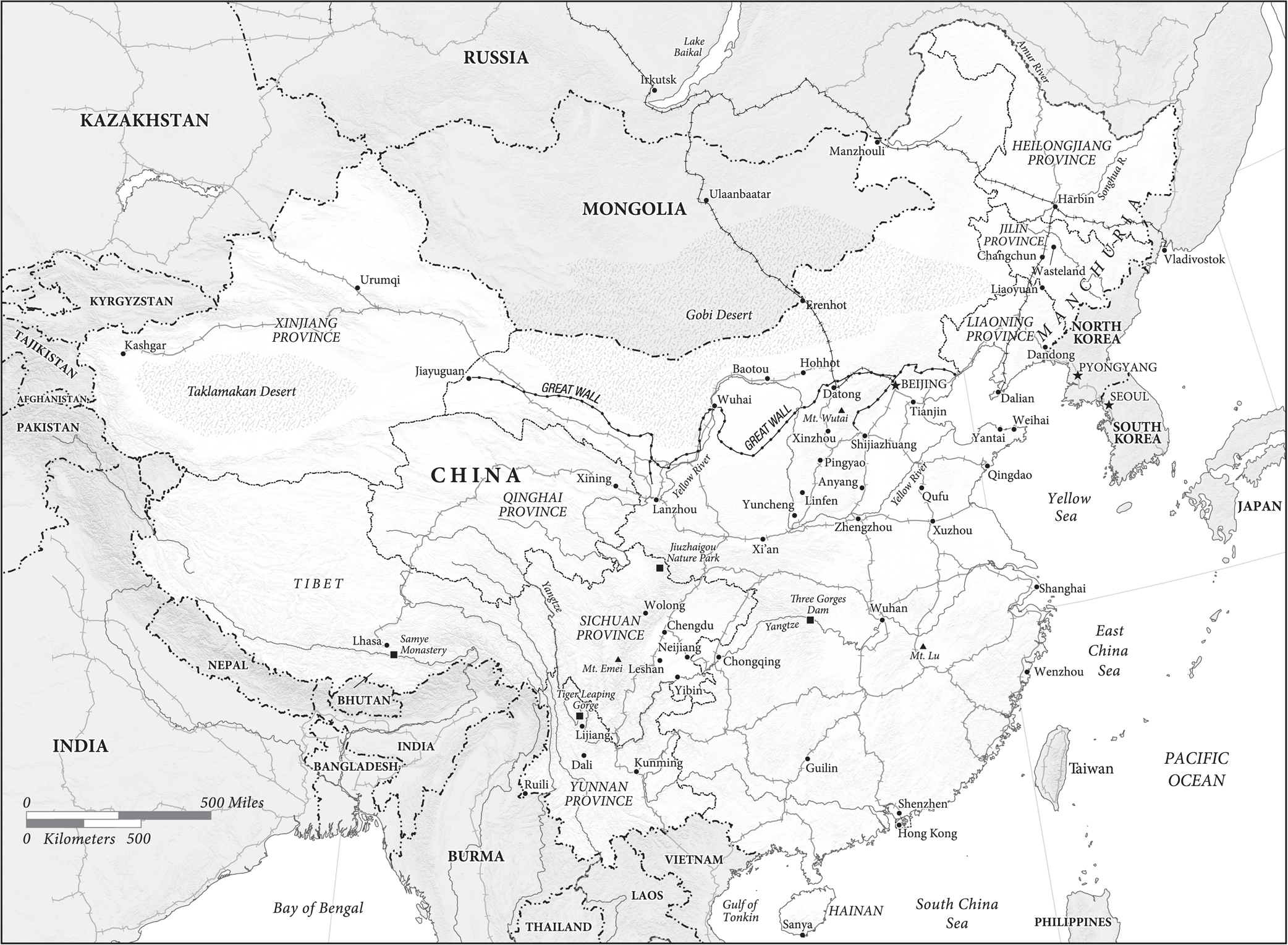

I didnt know Peace Corps was in China, I said, twirling the phone cord, stalling for time. In fact, the program had just tenuously begun, after its planned 1989 start was shelved following the crackdown on the nationwide demonstrations centered at Tiananmen Square. I was seventeen then, and when I heard of the bloodshed via my Beetles radio, I pulled to the roads shoulder, andcompletely out of characterburst into tears. I didnt know any Chinese people personally, had never read a book by a Chinese writer, and could not have found Beijing on a map. But suddenly a world event had punctured my bubble of enormous teenaged self-regard. Six years later I knew little about the country beyond the Great Wall, pandas, one billion people, fortune cookies, and the indelible image of a man standing in front of a tank.

In 1995, China was more of a pariah than a hot travel destination, academic subject, or journalist beat. The countrys ascent looked far from guaranteed; what looked preordained was its demise. One-third of Chinas population lived in poverty. The average Chinese worker earned only $500 each year. Permitting the Peace Corps to send English teachers coincided with China opening its doors to the wider world and its markets. Still, there were limits. When Chairman Mao held power, Chinese propagandists had condemned the Peace Corps as a tool of American imperialism. Rather than change its verdict, the current regime simply changed the program. Officially, the recruiter said, youll be called a U.S.-China Friendship Volunteer. He paused, and through the phone line I heard the rustle of papers. I dont know how to say it in Chinese.

I couldnt speak the language, either, of course. I didnt even know how it sounded. Not only was I wrong about fortune cookiestheyre from California by way of JapanI couldnt even use chopsticks. But this was it: Peace Corps take-it-or-leave-it final offerChina.

I was flat broke. Except for a calico named Barky that could not meow, I was single. I drove a failing black Crown Victoria that my students often mistook for a narcmobile, scattering like pins when I bowled into the school lot. I liked them; I had the patience, thick skin, and sense of humor for the job, and believed the best way to empower kids was to teach them to read and write at grade level by years end. The veteran teachers smirked at my rookie enthusiasm and shoulder-length hair, but praised my knack at reaching troubled teens. Nevertheless, to earn my certification I was paying full tuition to teach full time for free, and had no job prospects. The Internet was nascent and smartphones were a dream; I fed myself working graveyard shifts as a relay operator between deaf and hearing callers, and by writing reviews for the two city newspapers of cassettes mailed by record labels promoting new bands such as Radiohead, Green Day, and Oasis. In two weeks I was turning twenty-three; in a month I would graduate. What then? Slink back, unemployed, to my parents in Minnesota? Or hang up the phone, drive that Saturday to the Madison airport, meet the FedEx envelope from D.C., sign the federal forms and waivers, and do as the voice commands? China. Its not Club Med, its your life. You dont get to choose.