Mudlark

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

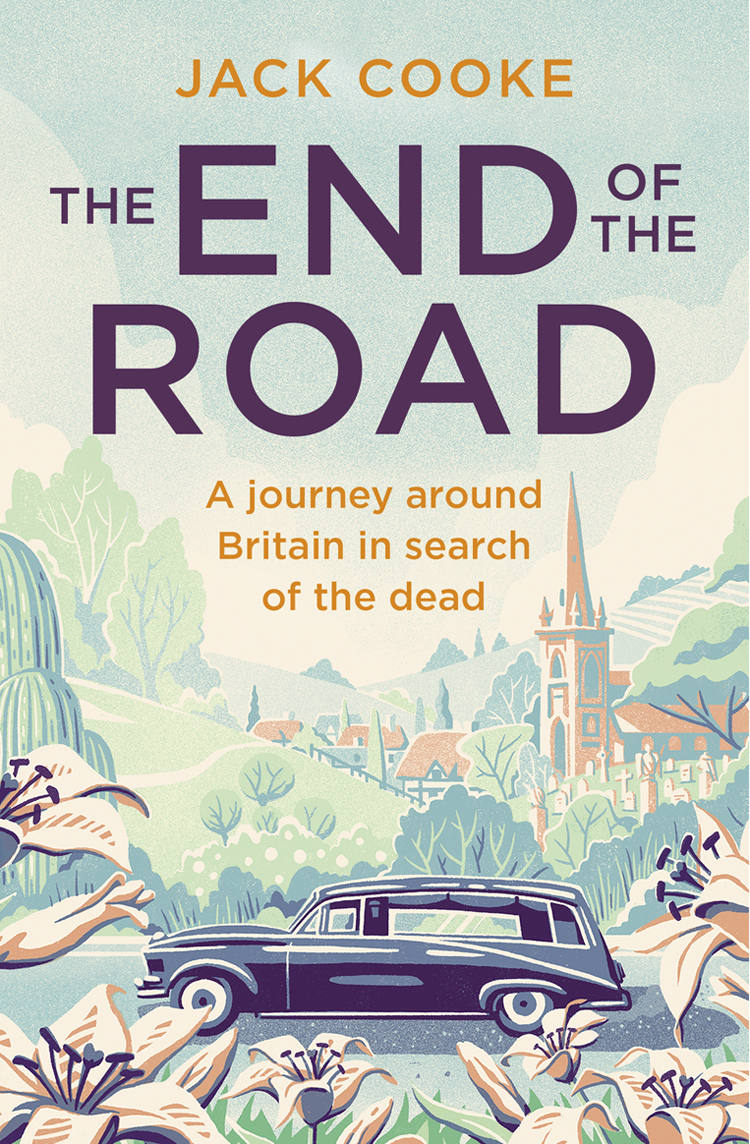

First published by Mudlark 2021

SECOND EDITION

Jack Cooke 2021

Cover layout design HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2021

Cover illustration James Weston Lewis/The Artworks

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Jack Cooke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008294717

Ebook Edition February 2021 ISBN: 9780008294724

Version: 2022-02-14

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

- Change of font size and line height

- Change of background and font colours

- Change of font

- Change justification

- Text to speech

- Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008294717

To my father and son

To bring the dead to life

Is no great magic.

Few are wholly dead:

Blow on a dead mans embers

And a live flame will start.

Robert Graves

Eternity is not something that begins after you are dead.

It is going on all the time. We are in it now.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

One dismal morning I walked into my local churchyard on a whim. I had no faith to carry me over the threshold, only the echoes of a few Our Fathers and the lyrics of half-remembered hymns. Yet the church beckoned to me each time I passed it, alone inside its brick walls and guarding the remains of a thousand people Id never met.

It began to rain as I reached for the latch on the churchyard gate. A rabbit bolted from behind a tombstone and disappeared beneath a stone cross, using the dead to hide from the living. In the church porch, gargoyles pulled faces at me from the safety of high pedestals.

The door was heavy and I had to lean into it. It swung slowly inward to reveal a dim and private world, the village noticeboard rustling softly as I passed, flyers for second-hand lawnmowers competing with curry nights in the pub. The air inside smelt of wood polish and damp prayer books. It felt close, heavy with the weight of expectation. The pews were empty and silent, save for flies that buzzed belly-up under the windows.

I reached a corner of the church where the shadows held their own communion. A large memorial stood with its back to the windows, pressed hard into the join between two walls. Amid this gloom knelt the figure of a man, his knees on a stone pillow and his hands joined together in prayer. The paint on his face had faded like an old dolls make-up and his gaze wandered among the ceiling beams.

Beneath him was a statue of his wife. The carving was much smaller and barely reached to my waist. Only the womans back could be seen, a great sweep of black drapery rising to a hood like a cobras silhouette. The form beneath the folds was thin and angular, unnaturally pinched in at the shoulders.

To look upon her face I had to squeeze between the memorial steps and the wall of the church, until we came nose to nose. In contrast to her husband, the womans gaze was direct, meeting my own. Her hair was drawn back from a high forehead, the stone scalp framed by the hoods sinister fork. A sharp nose ended in a small, tight-lipped mouth, oddly twisted at the corners. Her hands had been amputated at the wrist by neglect or vandalism, and I imagined them as forbidding as the rest of her thin, talon-like. Where her husbands epitaph ran the length of several stone tablets, the womans read only, Here lies Elizabeth Read.

Turning away from this fearful effigy I noticed a small stone flower, the size of my palm, had fallen from the tombs ceiling and lay unbroken on the floor. I picked it up and turned it over in my hands, wondering if I had just missed this moment in time.

I emerged from this reverie to find my eyes drawn again to the hooded form of Elizabeth Read. If the statue were a true likeness, she must have inspired as much dread in life as in death. Something brushed against the windows of the church, the shadow of tall weeds dancing against the glass, and I left the building to escape my own irrational fear.

In the churchyard, memories were less well preserved, the grave markers eroding like the coastline hidden beyond the boundary wall. The wind was in the east and I could hear breakers on the beach a mile distant, the great undertow sounding like it swept in among the graves. I counted two hundred tombstones listing forward or backward, as if their occupants were constantly rearranging themselves. The ground beneath them teemed with older bones, generations stacked in the soil.

Returning through the iron gates I paused by neighbouring graves. The first was the headstone of a sailor lost at sea, I harbour here below, the second a fresh grave not two weeks old, with the funeral flowers withered inside their wrappings.

The visit to the church reminded me how divorced I was from death. I inhabited a high-turnover world, a place of constant change that continued without pause or reflection. I ignored the dead because they interrupted life.

The possibility of dying was also easy to obscure with the act of living. Daily routine, a young family, good health; all of these provided a means of disregarding death. It existed only in the distant past and future, peripheral, made up of newspaper columns and other peoples tragedies. In my sheltered world people died out of sight and bodies vanished beyond doors and curtains, magicked from hospital wards to morgues to crematoriums, or closed coffins. Death was expedited, the whole process sped up, with digital memories supplanting deathbed vigils. Any bond my ancestors had with the deceased was broken.

Most of us live in denial of death. We practise unconscious alchemy, loath to accept our own mortality and searching for ways to prolong life in an age of modern medicine. Those already dead and buried are to be skirted around, side-stepped, wherever possible put to the back of our minds. The respect we accord them is also a way of establishing distance between them and us. In spite of our common fate we dissociate ourselves.

That night, when I went to bed and turned on my side, I found myself thinking once more of Elizabeth Read and the drowned sailor. I lay in a foetal position with my knees one on top of the other, a thin layer of skin separating the joints and flesh pressed hard between bones. As if for the very first time, I became acutely conscious of my own skeleton rubbing against itself.