PIANO

PIANO

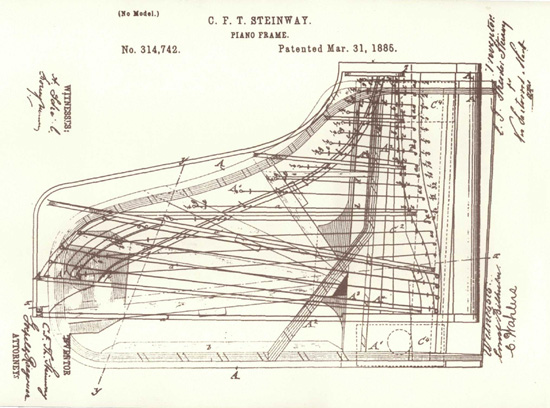

THE MAKING OF A STEINWAY CONCERT GRAND

James Barron

Times Books

Henry Holt and Company, LLC

Publishers since 1866

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

www.henryholt.com

Henry Holt is a registered trademark of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Copyright 2006 by James Barron

All rights reserved.

Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barron, James, 1954

Piano: the making of a Steinway concert grand /James Barron.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-7878-7

ISBN-10: 0-8050-7878-9

1. Steinway pianoConstruction. 2. Steinway & Sons.

3. Piano makersNew York (State)New YorkHistory. I. Title.

ML661.8.N7B37 2006

786.21973dc22

2005057172

Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums.

For details contact: Director, Special Markets.

First Edition 2006

Designed by Meryl Sussman Levavi

Photographs by Fred R. Conrad

Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg photograph: Collection of the New-York

Historical Society

Cristofori grand piano-forte photograph: Courtesy of the

Metropolitan Museum of Art

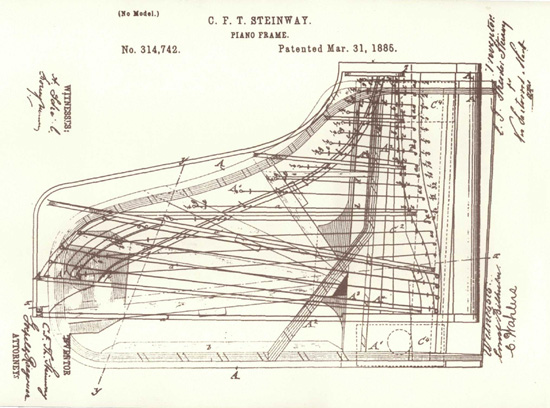

Inside a Concert Grand diagram by Mika Grndahl

Printed in the United States of America

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4

To Jane, for No. 252669and everything else

Contents

Prelude

BY THESE PEOPLE, IN THIS PLACE

Postlude

ON ITS OWN

Diagram:

INSIDE A CONCERT GRAND

Prelude

By These People, in This Place

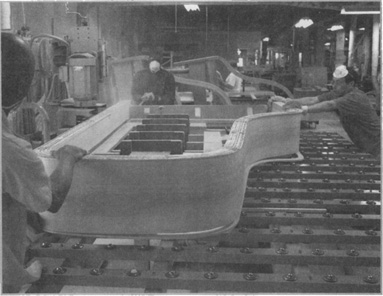

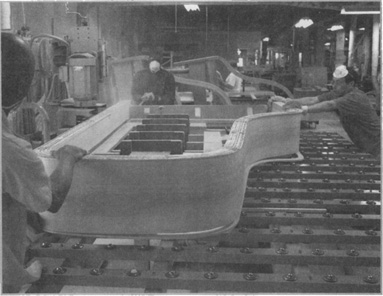

Steinway No. K0862 on its way to becoming a concert grand

The piano being a creation and plaything of men, its story leads us into innumerable biographies; being a boxful of gadgets, the piano has changed through time and improved at ascertainable moments and places.... Indeed, for the last century and a half, the piano has been an institution more characteristic than the bathtubthere were pianos in the log cabins of the frontier, but no tubs.

JACQUES BARZUN

Eighty-eight keys, two hundred and forty-some strings, a few pedals, and a case about the size ofyesa bathtub: every piano has pretty much the same curves outside and the same workings under the lid. But the biography of a piano is the story of many stories. It is the story of the fragile instruments from which all pianos are descended. And it is the story of contrasts. It is the story of nineteenth-century immigrants who struck it rich making pianos, and of more recent immigrants from Europe and Central America who are paid by the hour. It is the story of the family that virtually invented the modern grand piano, of brothers and cousins who drank, who hated the United States, or who dabbled in bulletproof vests and subways and land deals and amusement parks and the earliest automobiles. It is the story of a few workers who have exceptionally good ears and many who have never read a note of music or set foot inside Carnegie Hall. It is the story of men with a passion for motorcycles who have taught themselves snippets of Beethoven and Chopin and of others who tack photographs of Frank Zappa above their workbenches. It is the story of workers who have brought in special radios that receive the audio portion of television broadcasts so they wont miss their talk shows while they drill out the bottoms of keys and shove in tiny lead weights. It is the story of the place where they work, of factory floor camaraderie, of pleasant, unhurried work.

This book is the biography of one piano that was made by these people in this place. It is a concert grand that was built at the Steinway & Sons factory in New York City in 2003 and 2004. The main character will not make a sound for months. A big supporting castthe most experienced workers in a factory with a payroll of 450will fuss over it and fume at it.

Like all Steinways, that main character goes by a number, not a name: K0862. Like all other newborns, K0862 comes with hopes for greatness and with fears that it may not measure up to the distinguished family name it wears, and not bashfully. On its right arm the Steinway name is stenciled in big gold letters that an audience cannot miss; on its cast-iron frame the name is stamped in black letters that a camera closing on the pianists face cannot miss. There is no mistaking K0862 for a Baldwin or a Yamaha or a Bsendorfer.

Yet K0862 looks just like every other Steinway concert grand. It is eight feet, eleven and three-quarters inches long. It contains the same bewildering assortment of moving parts, thousands of tiny pieces of wood and felt and metal that bend and twist and rise and fall on command.

Pianists always say that a good piano has personality, but the workers know that a piano is a machine, or the eighteenth centurys idea of one. Talented tinkerers refined it later on improvisational wizards of hand tools who, little by little, made a good thing stronger, tougher, and, above all, enduring. But the piano remained an invention from an earlier time. Nineteenthcentury inventions had mechanized guts and world-changing goals, like doing in an hour what human hands took days to do. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Eli Whitney had invented the cotton gin. In the middle of the nineteenth century, Robert Fulton made his steamboat, Cyrus McCormick his reaper, and Isaac Merrit Singer his sewing machine. No one would say that a sewing machine has a personality. It is just a machine.

What a different machine is a piano: a machine with emotions, if that is possible, or at least emotional attachments. There are pianists who kiss their pianos every day, who touch the case as tenderly as they would touch a lovers cheek, who talk to their pianos in a way they talk to no one. Musicians regularly talk about the individual characteristics of this or that piano, the traits that make one a pleasure to play and the one next to it an agonizing slog. They dream of one that can deliver what Beethovens pupil Carl Czerny called a holy, distant and celestial Harmony.

Even before its first note sounds, the question hanging over K0862 is the question that hangs over every Steinway: How good is it? Will it be a lemon or the piano-world version of a zero-to-sixty delight? Will it sound like celestial harmony or a squadron of dive bombers, as the pianist Gary Graffman said of a Steinway he hated on first hearing (but came to love)? Will it surprise the Bach specialist Angela Hewitt, who considers Steinways made in New York to be powerful but rather strident, and in my opinion, clumsy? Will it match the piano that was the onstage favorite of Rachmaninoff and later Horowitz and, after retiring from concert life, became the living room piano in Eugene Istomins apartment? Will it be anything like the piano that Van Cliburn discovered during a late-night practice session before a concert in Philadelphia? That piano so captivated him that he offered to buy it then and there. Steinway told him to waitit was booked for at least nine months. He waited, and took it home in February 1990.

Will K0862 be good enough for a place in Steinways stable of concert pianos, the three hundred or so instruments that dominate the nations concert stages and recording studios? Will it be good enough to spend five years on a very fast track with a different rider every night?

Next page