All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

S CRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

Portions of this book have previously appeared in the OC Weekly a chunk of Becoming the Mexican and stray, genius lines too good to leave for a fish wrap, is all.

Calling you.

INTRODUCTION

This Is How We Do It in the OC (Dont Call It That)

Ive seen the Mexican future of this country, the coming Reconquistaand its absolutely banal.

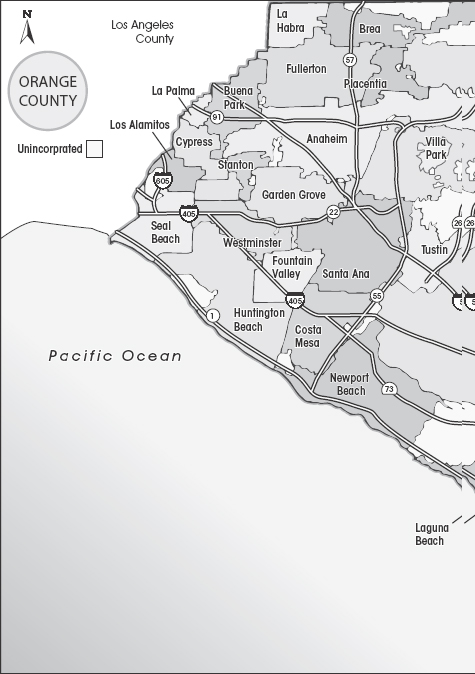

Our looming takeover is spreading across America and will resemble the neighborhood where my parents live in Anaheim, California, Mexico. The houses here all feature the same basic design: three bedrooms, two baths, a long living room connected to the dining room, divided from the kitchen by a bar. Half of the houses keep pools, the others backyards. Garages jut out from the dining room. Depending on the garages layout, the driveway either gently curves or rises upward at a dramatic angle, guaranteeing your cars undercarriage a daily scratch. About twenty years ago, this section of Anaheim was mostly white, baby boomers and their parents. Today? All Latino, save for the white man across the street who let his yard turn brown years ago.

Trembling yet? Really, the only way you would know its a Latino neighborhood is due to a very American phenomenon called conspicuous consumption. Every house has at least four cars parked outside: all nice, mostly large SUVs with a smattering of Toyotas occasionally parked on front lawns. Those lawns feature palm trees or rosesno cactuses yetand the richer households erect ornate fountains and stonework to rival the Alhambra. No Mexican flags flutter above doorways, no roosters crow at dawnat least not since Dad gave ours away because the cock kept assaulting dogs.

I moved out a couple of years ago at age twenty-seven, no longer content to share a bunk bed with my teenage brother. But a Mexican mothers breakfast beckons even the most prodigal of sons, so I return every Sunday morning to marvel at how Ozzie and Harriet our lives arehow absolutely banal. The Mexican conquest of the United States might not get televised, but it comes with a steaming bowl of menudo.

Dont believe me? Consider one Sunday, around November 2007.

I speed in around nine thirty in the morning, and damnit! No one is home.

Start dialing cell phones. Elsa, my school administrator of a sister, is organizing workshops for college-bound studentsmost of them Vietnamese, in a school thats majority Latino. Twenty-one-year-old Alejandrina settles in for a Starbucks study sessionshe wants to be a nurse, or maybe a teacher. Gabriel, the seventeen-year-old baby of our clan, who already towers over us all, is with Mom at a dentists appointment. My father? No answer.

Wheres the remote? The usual detritus of Householdus americanus clutters the living roomwater bottles, newspapers, backpacks. A Guitar Hero ax stands by the marbled fireplace. Jesus looms over me in the form of a huge oil painting bought at the swap meetstill dont know why Mami replaced our family portrait in favor of the Savior, considering she shows up at Mass as often as a Jew. To my right in a bookcase are small framed portraits of Elsa in her cap-and-gown from the University of California, Los Angeles, Alejandrinas high school graduation picture, and a younger Gabriel wearing a New York Yankees baseball cap (hes a Los Angeles Dodgers fan nowah, front-runners). Ken Burnss Baseball series is on the top shelf, missing episode 7. And smack-dab in the middle is a photo of me grinning, holding a half-eaten tamale. Speaking of tamales, I toss three in the microwaveone dessert, one pork, one made with cheese, chicken, and jalapeos, all leftovers from our Thanksgiving dinner.

The doorbell rings. Its my father. Hes dressed for workjeans, cowboy boots, baseball capand his smile bends an increasingly salt-and-pepper mustache.

Wassappenin, macho man? Papi booms in heavily accented English. I turn away, embarrassed. Ven, ven, ven gimme a hand-chake! We embrace. He beams.

Dnde estaba? I ask. Where were you?

En la cafeteria, he responds, his inexplicable nickname for a doughnut shop about five minutes away.

As long as I can remember, my father has spent his Sunday mornings at JAX Donuts House, a run-down coffee house across the street from Anaheim City Hall. Gentrification, redevelopment, and changing demographics have yet to kill this eyesore: when Starbucks usurped JAXs original location, the owners moved a couple doors down, and its mostly Mexican clientele followed. The Cambodians who own the small store dont fry the best doughnuts (if you ever stop in, order the cinnamon roll and ask for a hell of a lot more frosting), yet thirty to forty middle-aged Mexican men regularly hang out there every weekendnot to harass passing pickups for the chance to pound nails, but to live the good life. Theyre all men from Jerez, a city of about fifty-six thousand in the central-Mexican state of Zacatecas. More specifically, almost all of the men are from El Cargadero, the tiny village where my mother was born and whose migration to Anaheim captures the postmodern Mexican experience as well as anything.

But when these men meet, they dont chatter about politics or immigration reform. They gossip. Chismean como viejas! my mom has sighed numerous times. They gossip like old ladies! Its true: these burly machos, naturally light skin eternally sunburned due to years working outside, chatter almost exclusively about the goings-on in El Cargaderowhos marrying whom, which son or daughter got in trouble or went off to college, stories of their childhood. That their Mexican hometown is now three-quarters empty doesnt bother anyone.

On this particular Sunday morning, my father discussed an upcoming trip to his native Jomulquillo, a village just south of El Cargadero. Hes in charge of the comit Guadalupana, a group of people who live in the United States but raise funds for a celebration in Jomulquillo for the feast day of the Virgin of Guadalupe on December 12. For the past four years, my father and others have raised thousands of dollars just so a brass band can play for twenty-four continuous hours, a childhood tradition they fondly remember but which died for a time as Jomulquillo hemorrhaged its residents to el Norte .