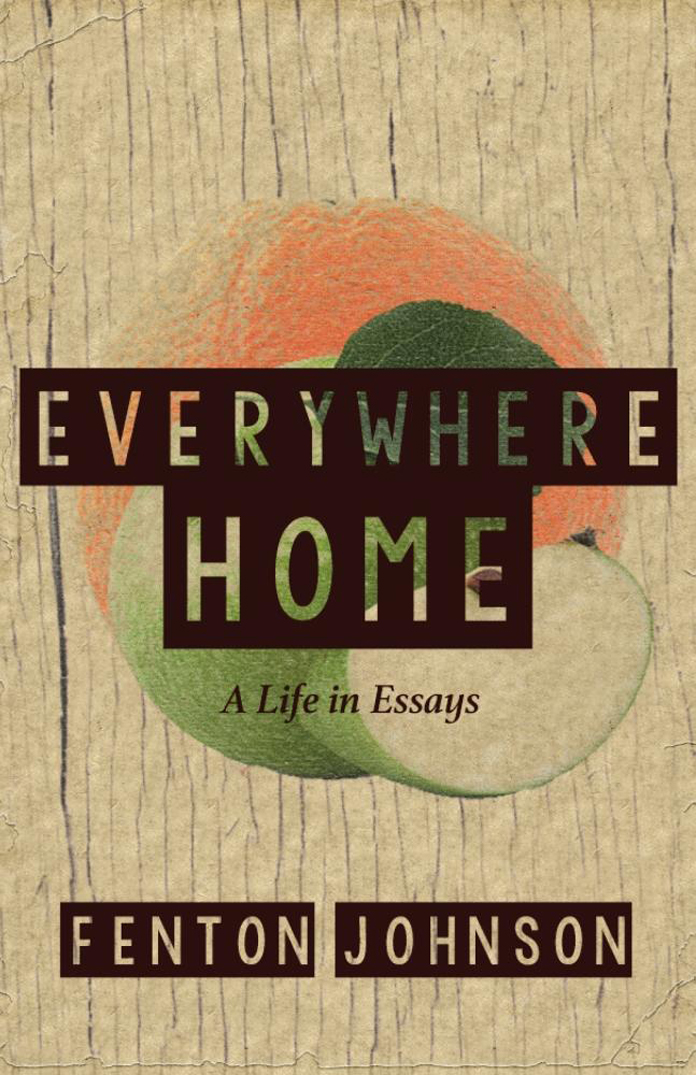

Copyright 2017 Fenton Johnson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Johnson, Fenton, author.

Title: Everywhere home: a life in essays / Fenton Johnson.

Description: First edition. | Louisville, KY: Sarabande Books, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016059114 | ISBN 9781941411445

Subjects: LCSH: Johnson, Fenton--Homes and haunts. | Authors, American--21st century--Biography. | College teachers--United States--Biography. | Gay men--United States--Biography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Literary. | LITERARY COLLECTIONS / Essays. | LITERARY COLLECTIONS / American / General.

Classification: LCC PS3560.O3766 Z74 2017 | DDC 818/.5403 [B] --dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016059114

Interior and exterior design by Sarabande Books.

Sarabande Books is a nonprofit literary organization.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. The Kentucky Arts Council, the state arts agency, supports Sarabande Books with state tax dollars and federal funding from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Also by Fenton Johnson

Crossing the River

Scissors, Paper, Rock

Geography of the Heart: A Memoir

Keeping Faith: A Skeptics Journey among Christian and Buddhist Monks

The Man Who Loved Birds

Documentary narrations:

Stranger with a Camera

La Ofrenda: Days of the Dead

I Just Wanted to Be Somebody

for those who gave and give their lives for others

among them Laurie Johnson Boone (1949-2012)

Like those wandering monks

who, calling nowhere home, are everywhere home.

Jane Hirshfield, To Speech

Guide

(2016)

I ordered my first drink at the Club 68 in Lebanon, Kentucky, thirty winding country miles east of my childhood home. The Club was owned by Lebanese Christiansa long story, but the short version is that prosperous Anglos have always farmed out what they call vice to black people and rural people and newly arrived immigrants, people the Anglos can trash and persecute and imprison after they service the Anglo obsession with sin. The Irish, the Jews, the dark-skinned people, the hillbillies, and of course the queers, selling hooch or pot or heroin or meth or sex to the prosperous and, for our trouble, thrown in the slammer after the goods are passed but before the money changes hands.

Fleeing violence abroad, these Lebanese Christians settled in Lebanon, a town of five thousand which, some two centuries earlier, Presbyterian Scots had named after the Middle Eastern homeland of the Club 68s owners. An exile and an outlier, Hyleme George, patriarch of the family, situated his nightclubs on the chitlin circuit, an assemblage of roadhouses scattered throughout the then-segregated South, where African American musicians, en route from winters in New Orleans to summers in Chicago, performed in exchange for a room and a meal and a percentage of the door. Fresh from the multicultural patchwork of the Middle East, unburdened by the Souths crushing obsession with race, George understood that white audiences would pay to see and hear black artists. He hired a black manager and cross-programmed acts among his clubs, one all-black, another all-white, the third mixed, and the list of the musicians he hired to play in this town is a roll call of midcentury American blues and jazz and rock n roll: B. B. King, Otis Redding, Jimi Hendrix en route from military service at Fort Campbell in western Kentucky to the formation of his own band in Cincinnati, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, Jackie Wilson, the Supremes, James Brown, Ray Charles, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, Etta James, Sam & Dave, Wilson Pickett, Percy Sledge, Eddie Floyd, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, Junior Parker, Joe Tex, LaVern Baker, the Coasters, the Shirelles, the Platters, Count Basie, Nat King Colenot to mention a few white boys tagging along for the ride, among them Creedence Clearwater Revival, the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra, and Steppenwolf.

I had a friend who was sixteen and thus possessed of a drivers license and his parents car. I had no idea who was playing that night of my first purchased drink and didnt much care. My friend and I were only looking to get drunk and, as was widely known, the clubs in Lebanon served alcohol to anyone tall enough to push a bill across the bar. The Club legally held maybe three hundred people; that night there were easily five hundred, under a ceiling twenty feet high. Most of us were male. All of us were white. This was 1968, at the Club 68, on US Highway 68. I was fifteen years old. Onstage, Ike and Tina Turner and the Ikettes.

I do not recall what Ike and Tina sang. What I recall is the discovery of desire. What Tina Turner did with her body I hadnt conceived that anybody could do with a body. As a gay boy unaware that there were words to name what I was, I wasnt in heat in the manner of most men around me. Nonetheless Miss Turner taught me that evening that the body was something more than a suitcase for transporting the brain. Almost fifty years later I of the too-vivid imagination have to work to imagine how she could strut and entice and seduce five hundred screaming drunk Anglo country boys. That is what we call art and she a true artist, though as I write that sentence I speculate that she must have reveled in asserting her power, her black woman artists power, in one of the few ways and places available to her.

And so I encountered in art, her art, the catalyst for my lifelong project of dismantling Western civilizations separation of body from mind, heart from soul, in what was shown, not told that evening at the Club 68 by Anna Mae Bullock, former Nutbush, Tennessee, Baptist church choir girl: no duality, no separation, love your neighbor as yourself, we are all one in Christ Jesus, we are all one in desire.

Driving home, my drunk friend got us lost and didnt get me to my parents house until four A.M. For the first and last time, my mother was waiting up. In her expression I understood that she had thought that I, her youngest son, was not going to be a hell-raiser like her three previous sons, and she was sorely disappointed. Soon thereafter segregation ended, at least officially, and doors opened for black artists to perform in first-class venues, even in the South. The chitlin circuit faded into history. A few years after that, Tina left Ike. I doubt she ever again performed in a venue so humble. But she had awakened a force that was not to be denied, and though I am not condoning that drunk drive home and though I mourn all those fine men and women lost to AIDS I have no regrets about my forays into the demimonde, the days and nights given over to seeking connection, communion with the gods, with God.

Not long afterward I graduated from high school and went wandering, an ancient and exacting and honorable calling.

Later in these pages I will confess that I do not believe in time, that I do not believe in death. Looking out the window on a chill December day in my beloved Kentucky, my left ankle broken and in a cast from an accident involving a hibernating groundhogs hole in the woods surrounding the hermitage of the Trappist monk, mystic, and writer Thomas Merton, I find the sources of that observation so obvious as to need no explanation. The bare trees raised limbs etch lines against the pale blue winter sky; another six months and these same trees will present a curtain of green. Only the smallest liberation of consciousness is required to understand me, the groundhog, the trees, and you as seamlessly unified and continuous elements of that same cycle of birth and death and rebirth.